South Asian Journal of Life Sciences

Research Article

Diversity of Spider Fauna (Arachnida: Araneae) in Different Ecosystems, Eastern Ghats, Southern Andhra Pradesh, India

Harinath Palem, Suryanarayana Kanike, Venkata Ramana Sri Purushottam*

Department of Zoology, School of life Sciences Yogi Vemana University, Vemanapuram, Y.S.R. Kadapa District, Kadapa- 516003, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Abstract | The objectives of the present study was to explore the diversity and abundance of spider fauna at different habitats. This article also presents a study on the distribution and current status of different spider species in four ecosystems of Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh. The basic goals of this study was to gather baseline distribution data on spiders by undertaking exhaustive surveys at some selected sites of four ecosystems of Andhra Pradesh. viz., Sri Lankamala wildlife Sanctuary, (Kadapa district), Rapur Ghat forest, (Nellore district), Pallakondalu, (Kadapa and Chittoor district), Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve forest (Kadapa, Chittoor and Nellore district). During our analysis, a total of 19, 25 and 31, 41 spider families were recorded respectively from these four ecosystems. The statistical and diversity indices for each study sites was calculated. Such surveys are vital for the conservation of these creatures in the light of climate change and building a biodiversity database of spider fauna of Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh in near future.

Keywords | Spider diversity, Sri Lankamala wildlife Sanctuary, Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve forest, Eastern Ghats

Editor | Muhammad Nauman Zahid, Quality Operations Laboratory, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan.

Received | September 08, 2016; Accepted | December 10, 2016; Published | December 15, 2016

*Correspondence | Dr. S.P. Venkata Ramana, Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, Yogi Vemana University, Vemanapuram, Kadapa, Y.S.R. Kadapa District- 516003, Andhra Pradesh, India; Email: akshay@yogivemanauniversity.ac.in; haributterfly.yvu@gmail.com

Citation | Palem H, Kanike S, Purushottam VRS (2017). Diversity of spider fauna (Arachnida: Araneae) in different ecosystems, Eastern Ghats, Southern Andhra Pradesh, India. S. Asian J. Life Sci. 4(2): 51-60.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.14737/journal.sajls/2016/4.2.51.60

ISSN | 2311–0589

Copyright © 2017 Palem et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Being a mega diverse country rich in both flora and fauna. Knowledge about the diversity of these species Spiders is one of the most diverse groups of organisms. Though spiders form one of the most ubiquitous and diverse groups of organisms existing in India, their study has always remained largely neglected. They are largely been ignored because of the human tendency to favourome organisms over others of equal importance, because they lack a universal appeal (Platnick, 2011).

The current global list of spider fauna is approximately 42,055 belonging to 3821 genera and 110 families (Platnick, 2011). The spider fauna of India is represented by 1520 spider species belonging to 377 genera and 60 families (Sebastian and Peter, 2009). There still exist major gaps in our knowledge of the biodiversity of spiders in many areas within varied ecosystems of India. Spiders are an important but generally poorly studied group of arthropods that play a significant role in the regulation of insect pests and other invertebrate populations in most ecosystems. Despite their abundance, ecological importance, and ubiquitous occurrences, spiders are seldom included among organisms surveyed for extensive studies and conservation. General Series on fauna published by Gazetteer of India, Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh, records a total of 90 species of spiders belonging to 14 families (Tikader, 1980). Long term and meaningful conservation require the complete knowledge of the species in various ecosystems. In view of this, it is imperative to undertake studies serveys concerning the spider diversity of Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh. Some recent workers on Indian spiders include Majumdar and Tikader (1991), Reddy and Patel (1992), Biswas and Biswas (1992), (2003), Biswas and Majumdar (2000), Sadana and Goel (1995), Biswas et al. (1996), Patel and Vyas (2001), Patel (2003a) and (2003b).

The significance of insects in ecology needs no emphasis. Spiders also have a very significant role to play in the ecology by being exclusively predatory (Werners and Raffa, 2000) and thereby regulate insect populations. The Spiders and insects are both Arthropods, but some important differences are observed in both the groups. Spiders are actually arachnids; they have eight legs but insects posses’ six legs; which is a remarkable difference. Like insects, the spider doesn’t possess antennae. The main parts of spider’s body are also different from insects. The spider has head and thorax without abdomen fused into one structure called Cephalothorax. The arachnids constitute the second largest class (7%) of documented arthropods and it is estimated that 8.3% of arthropods are arachnids.

Thus arachnids rank second among arthropods. The order Araneae of class arachnida consists of spiders. The sub-orders mesothelae and orthognatha consist of primitive spiders, and the sub-order labidognatha includes the most recent spiders. All spiders are venomous but only a few species are non-venomous enough to harm humans. However, the venom of some spiders is useful in the study of neuromuscular and cardiac pharmacology. While there are only a few spiders in India that are really dangerous to humans, there are significant numbers around the world.

The coloration of spiders is varied and is paralleled only by insects. Spiders may also serve as biocontrol agents (Harinath et. al., 2014). In spite of several applied values mentioned above, spiders have received cursory attention. In conservation efforts, often “charismatic” species like birds and mammals draw most attention and ecological significant groups like spiders are often neglected.

Spiders belong to the class Arachnida of the phylum Arthropoda, animals that possess jointed appendages and a chitinous exoskeleton. The members of the class Arachnida are characterized by two body regions, the cephalothorax having four pairs of segmented legs attached it, and the abdomen. Unlike insects, arachnids do not have antennae. Spiders can be clearly differentiated from another arachnid by the presence of the pedicel, a narrow stalk that joins the cephalothorax and the abdomen. In other arachnids, the two parts of the body are fused so that they appear as one. Spiders are also unique as they possess spinnerets situated near the hind end of the abdomen which produces silk.

International Studies

The distribution and diversity of spiders have drawn the attention of naturalists in different parts of the world since the eighteenth century. The studies on the systematics of spiders had developed rapidly with the increasing knowledge about the group. Petrunkevitch (1933) provided an inquiry into the natural classification of spiders based on a study of their internal anatomy. Bonnet (1945) gave an overview on the taxonomy of spiders, which covers about two centuries work. Lehtinen (1967) prepared a comparative and phylogenetic system of classification.

Davies and Zabka (1989) provided illustrated keys and notes to genera of jumping spiders (Araneae: Salticidae) in Australia which were helpful in identifying some 57 genera of that region. Cambridge (1969a) included all the genera and species of spiders described after Roewer’s (1955). He gave a systematic list of about 7000 species described in the literature from 1940 to 1981. Platnick (1989) added new taxa and taxonomic references and provided synonyms of various taxa. He also provided a bibliography of work relating to Araneae published from 1981 to 1987. Roberts (1995) published a field guide to the spiders of Britain and North Europe. Heimer and Nentwig (1991) recorded 1100 species from Central Europe.

The distribution of spiders in the rice field of South Asia has been well recorded and illustrated by Barrion and Litsinger (1995). The Nearctic fauna is perhaps 80% described in New Zealand and Australia Other areas, especially Latin America, Africa and the Pacific region are much poorly known for the spider. Song and Zhu (1997) worked on the families Thomisidae and Philodromidae from China. They dealt with a total of 32 genera and 145 species. A compendium of the spider fauna of North America was provided in Kaston (1978), and Vincent Roth’s field guide. According to The World Spider Catalog, Version 12.0 by Platnick (2011), the updated lists documented 42473 species of spider worldwide belonging to 3849 genera and 110 families.

National Statues

Spiders are extremely abundant throughout the country, but our knowledge of the Indian spiders is extremely fragmentary. Studies on Indian spiders have been done earlier by several European workers and later by Indian Arachnologists. Two of the earliest contributions on Indian spiders were made by Stoliczka (1869) and Karsch (1873). Simon (1892) recorded many species from the Himalayas and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Blackwell (1867), Karsch (1873) were the pioneer workers on Indian spiders. They described many species from India, Burma, and Sri Lanka. Cambridge (1869a) worked in the Indian, Sri Lankan, and Minicoy islands. Simon’s works on Asian region (1892), Indochina and the Indian region provide early information on spiders of the oriental and Indian region.

Tikader (1980) and (1982) described spiders from India. Tikader (1980) compiled a book on Thomisid spiders of India, comprising of 2 subfamilies, 25 genera, and 115 species. Of these, 23 species were new to science. Descriptions, illustrations, and distributions of all species were given. Keys to the subfamilies, genera, and species were provided. He reviewed the general taxonomic characteristics with reference to Thomisidae. Tikader and Biswas (1981) studied 15 families, 47 genera and 99 species from Calcutta and surrounding areas with illustrations and descriptions. In the twentieth century, Patel and Redddy (1989), documented several studies on Indian spiders. Pocock (1895-1901) recorded two hundred species from India, Burma and Ceylon in his work ‘Fauna of British India, Araneae’ (Pocock, 1900a). His book provided the first list of spiders, along with enumeration and new descriptions in British India based on spider specimens at the British Museum, London. Pocok (1895), (1899a) and (1900b) also reported on Oriental Mygalomorphs, new species of Indian arachnids (Pocok, 1899b, 1901) and spiders of Lakshwadeep provides with the one of earliest information from these regions.

Gravely worked on mimicry in spiders, mygalomorph spiders and added information to Indian spiders. Tikader (1987) also published the first comprehensive list of Indian spiders, which included 1067 species belonging to 249 genera in 43 families. Contributions made by Sinha (1951) on Lycosidae and Araneidae are also important. Tikader and Biswas (1981) and Biswas and Biswas (1992) have described spiders from Bengal. Spider fauna of Gujarat has been studied mainly by Patel and Vyas (2001), Srinivasulu (2000), Srinivasulu et al. (2004a), (2004b) and (2008) have described spiders from Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Tikader (1980) and (1982) described many species from the families Thomisidae, Philodromidae, Lycosidae, Araneidae and Gnaphosidae from all over India. Uniyal and Hore (2006) has prepared a 10 checklist of 186 species of spiders in 69 genera under 24 families and described many new species of spiders from Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh region. A brief account on spiders is also provided by Vijayalakshmi and Ahimaz (1993) in the book titled ‘Spiders: An Introduction’. Spiders of protected areas in India have received very little attention.

The main work has been conducted by Gajbe (1995a) in Indravati Tiger Reserve and recorded 13 species. Patel (2003) recorded five species and Uniyal and Hore (2006) 14 species from Kanha Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh. Patel and Vyas (2001) conducted biodiversity studies in Hingolgarh Nature Education Sanctuary, Gujarat and described 56 species of spiders belonging to 34 genera distributed in 18 families. Patel (2003) described 91 species belonging to 53 genera from Parambikulum Wildlife Sanctuary, Kerala. Uniyal and Hore (2006) recorded a total of 19 species of spiders belonging to 10 families from Ladakh. Centre for Indian Knowledge System, Chennai has also conducted ecological studies of spiders in a cotton agroecosystem of Guindy National Park. De (2001) listed 19 species of spider from Dudhwa Tiger Reserve in his management plan. Uniyal (2004) studied spiders as conservation monitoring tools for protected areas. Studies on spiders are also conducted in agroecosystems mainly in rice fields and coffee plantations (Sebastian and Peter, 2009; Kapoor, 2008). Hore and Uniyal (2008a) worked on the spider assemblages and their diversity and composition in different vegetation types in Terai Conservation Area (TCA). Hore and Uniyal (2008a) worked on spiders as indicator species for monitoring of habitat condition in TCA. Hore and Uniyal (2008a) also studied the effect of fire on spider assemblages in TCA. Biswas and Biswas (2004) contributed significantly to spider diversity by rendering comprehensive lists of newly recorded spider species from Manipur and West Bengal. Siliwal et al. (2005) prepared an updated checklist of Indian spider and provided taxonomic re-evaluation of described species, Biswas and Biswas (2004) reported 127 species of spiders belonging to 49 genera under 17 families from Uttarakhand state. Siliwal et al. (2005) prepared an updated Checklist of Indian spider and provided taxonomic re-evaluation of described species, referred 1442 species belonging to 361 genera of 59 families from the Indian Region. Of the 1442 species, 1002 were endemic to the Indian mainland. Recently, 1520 species belonging to 361 genus and 61 families were reported by Sebastian and Peter (2009) in the book ‘Spiders of India’. However, the information available from the Eastern Ghats part of India especially, the Southern and sub-Tirumala foothills region, is far from complete. The knowledge on diversity and distribution of spiders in Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats is sparse as compared to other regions. Thus, a serious need exists to explore spider diversity in the Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats part of the country especially the higher altitudinal regions.

Materials and Methods

Study sites

The spider inventory studies were conducted from Jan. 2015 to Dec. 2015 at four study sites from Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh (Table 1, Figure 1).

Identification

Spiders were observed using stereo zoom microscopes for studying identification keys. All specimens were identified using the taxonomic keys for Indian spiders given by Tikader (1980), (1982) and (1987).

Experimental Design and Sampling Methods

Spider Inventory work was conducted at all four ecosystems by different groups of scientists and workers. Two surveys were conducted per season at all study sites. Five 20 x 20 mt. quadrates were taken for extensive surveys.

Figure 1: Study areas

Table 1: The spider inventory studies were conducted from Jan. 2015 to Dec. 2015 at four sites from Andhra Pradesh

|

Study Sites |

Geographical Location |

Habitat type |

|

Sri lankamala wildlife Sanctuary (Kadapa district) |

14°45' - 14°72' N and 79°07' - 78°80' E |

Lanka Malleswara Wildlife Sanctuary is best known as a mainstay habitat of endangered insects and rare species of a bird called the Jerdon's Courser (Rhinoptilus bitorquatus) |

|

Rapur Gat forest (Nellore district) |

14°19' N -79°.53' E |

Rapur Gat forest, a range of hills that form a part of the Eastern Ghats in the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. tropical and subtropical moist forests |

|

Pallakondalu hills (Kadapa district) |

14°28′ - 14.47° N and 78°55′ - 78.92° E |

Palkonda Hills are a range of hills that form a part of the Eastern Ghats in the Southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. An exceptional mix of the tropical southern dry mixed deciduous types |

|

Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve |

13°38’ - 13°55’ N and 79°07’ - 79°24’ E |

Seshachalam Hills, the first Biosphere Reserve in Andhra Pradesh, is located in Southern Eastern Ghats of Chittoor and Kadapa districts. It is spread over 4755.99 Km. The vegetation 2 is a unique mix of the tropical southern dry mixed deciduous types |

All surveys were conducted in the morning hours between 7:00 am to 11:00 am.

Spiders were collected by adopting standard sampling techniques as described below:

1. Beating sheets: Spiders from trees and woody shrubs were dislodged and collected on a sheet by beating trees and shrubs with a standard stick. 10 beats per tree or shrub were employed in each quadrat.

2. Sweep netting: Spiders from herbaceous-shrub-small tree vegetation were collected using standardized insect-collecting net. 20 standard sweeps were employed per quadrat.

3. Active searching and hand picking: Spiders from all three layers were collected using this method. In this method spider, specimens were actively searched for 30 minutes per quadrat for searching under rocks, logs, ground debris, and loose dead barks of trees etc. Some other methods are followed.

Collection

Foliage spider fauna was collected from forest plantations. Two methods viz., jarring and direct hand picking were available and here we are applied only direct hand picking method.

Direct Hand Picking: Collection of most web-building species was made early in the morning. Spiders other than weavers were also collected form plants by hands.

Field Data Record

Data collector for spider available plants, date of collection, and locality of each specimen was recorded in the field data book.

Identification and Preservation of Specimens

Collected dead specimens (Table 2) were transferred in to 70% alcohol for later identification. Accurate identification of the family, genus and species level was only feasible with the adult specimen. The identification of the spider relies heavily on the 30 genitalia. Thus identifying immature spiders to species level was considered impractical as sexual characters are needed for species level identification (Edwards, 1993). Identification and classification were also done on the basis of morphometric characters of various body parts. The identification was also based on salient features like presence of two or three claws, presence or absence of cribellum, paraxial or diaxial chelicerae, the presence of one or two pairs of book lungs. A detailed taxonomic study was carried out based on the various keys and catalogues provided by Dayal (1935), Tikader (1980), (1982), Tikader and Biswas (1981), Davis and Zabka (1989), Biswas and Biswas (1992), (2003), (2004), Barrion and Litsinger (1995), Song and Zhu (1997), Nentwig et al. (2003), Platnick (2011) and other relevant literatures. Voucher specimens were deposited at Entomology research museum, Yogi Vemana University, Kadapa.

Size

Spiders occur in a large range of sizes. The smallest, Patu digua from Colombia, are less than 0.37 mm (0.015 in) in body length. The largest and heaviest spiders occur among tarantulas, which can have body lengths up to 90 mm (3.5 in) and leg spans up to 250 mm (10 in).

Table 2: Systematic list of recorded spiders in the Ecosystems

|

Family |

Scientific name |

Guild |

Family |

Scientific name |

Guild |

|

Araneidae |

Araneus bilunifer |

Orb-web builders |

Lycosidae |

Pardosa sumatrana |

Ground Hunter |

|

Argiope anasuja |

Orb-web builders |

Pardosa sp. |

Ground Hunter |

||

|

Argiope aemula |

Orb-web builders |

Hippasa pisaurina |

Ground Weaver |

||

|

Argiope pulchella |

Orb-web builders |

Oxyopidae |

Oxyopes sp. |

Stalkers |

|

|

Neoscona mukerjei |

Orb-web builders |

Pholcidae |

Pholcus phalangioides |

Scattered line weavers |

|

|

Neoscona theis |

Orb-web builders |

Crossopriza layoni |

Scattered line weavers |

||

|

Neoscona nautical |

Orb-web builders |

Artema Atlanta |

Scattered line weavers |

||

|

Neoscona lugubris |

Orb-web builders |

Pisauridae |

Pisaura sp. |

Ambushers |

|

|

Neoscona excelsus |

Orb-web builders |

Salticidae |

Plexyppus payakullii |

Stalkers |

|

|

Cyclosa confrega |

Orb-web builders |

Marpissa decorata |

Stalkers |

||

|

Cyrtophora citricola |

Orb-web builders |

Tetragnathidae |

Tetragnath mandibulata |

Orb-web builders |

|

|

Zygilla sp. |

Orb-web builders |

Tetragnath listeri |

Orb-web builders |

||

|

Clubionidae |

Chirachanthium saraswatii |

Ground runners |

Leucauge decorate |

Orb-web builders |

|

|

Eresidae |

Stegodyphus socialis |

Sheet-web |

Leucauge tessellate |

Orb-web builders |

|

|

Stegodyphus pacificus |

Sheet-web |

Therididae |

Theridion tikaderi |

Ground runners |

|

|

Gnaphosidae |

Drassodes parvidens |

Ground runners |

Cyllognatha surajbae |

Ground runners |

|

|

Hersillidae |

Hersillia savignyi |

Foliage Hunter |

Thomisidae |

Camaricus sp. |

Ambushers |

|

Sparassidae |

Olios sp. |

Foliage Hunter |

Thomisus sp. |

Ambushers |

|

|

Lycosidae |

Lycosa poonaensis |

Ground Hunter |

Uloboridae |

Uloborus donolius |

Ground runners |

|

Lycosa pictula |

Ground Hunter |

Uloborus sp. |

Ground runners |

||

|

Pardosa biramanica |

Ground Hunter |

Silk Production

The abdomen has no appendages except those that have been modified to form one to four (usually three) pairs of short, movable spinnerets, which emit silk. Each spinneret has many spigots, each of which was connected to one silk gland. There are at least six types of silk gland, each producing a different type of silk. Silk was mainly composed of a protein very similar to that used in insect silk. It was initially a liquid and hardens not by exposure to air but as a result of being drawn out, which changes the internal structure of the protein. It was similar in tensile strength to nylon and biological materials such as chitin, collagen and cellulose, but is much more elastic in other words it can stretch much further before breaking or losing shape Even species that do not build webs to catch prey use silk in several ways: as wrappers for sperm and for fertilized eggs; as a “safety rope”; for nest-building; and as “parachutes” by the young of some species.

Coloration

Only three classes of pigment (ommochromes, bilins, and guanine) have been identified in spiders, although other pigments have been detected but not yet characterized. Melanins, carotenoids and pterins, very common in other animals, are apparently absent. In some species the exocuticle of the legs and prosoma was modified by a tanning process, resulting in brown coloration. Bilins are found, for example, in Micrommata virescent, resulting in its green colour. Guanine was responsible for the white markings of the European garden spider Araneus diadematus. It was in many species accumulated in specialized cells called granulocytes. In genera such as Tetragnatha, Leucauge, Argyrodes or Theridiosoma, guanine creates their silvery appearance. While guanine is originally an end-product of protein metabolism, its excretion can be blocked in spiders, leading to an increase in its storage. Structural colours occur in some species, which are the result of the diffraction, scattering or interference of light, for example by modified setae or scales. The white prosoma of Argiope results from hairs reflecting the light, Lycosa and Josa both have areas of modified cuticle that act as light reflectors.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Spiders reproduce sexually and fertilization was internal but indirect, in other words, the Spiders reproduce sexually and fertilization is internal but indirect, in other words, the sperm is not inserted into the female’s body by the male’s genitals but by an intermediate stage. Spiders generally use elaborate courtship rituals to prevent the large females from eating the small males before fertilization, except where the male was so much smaller that he was not worth eating. In web-weaving species, precise patterns of vibrations on the web are a major part of the rituals, while patterns of touches on the female’s body are important in many spiders that hunt actively. Gestures and dances by the male are important for jumping spiders Females lay up to 3,000 eggs in one or more silk egg sacs, which maintain a fairly constant humidity level. In some species, the females die afterward, but females of other species protect the sacs by attaching them to their webs, hiding them in nests, carrying them in the chelicerae or attaching them to the spinnerets and dragging them along.

Baby spiders pass all their larval stages inside the egg and hatch as spider-lings, very small and sexually immature but similar in shape to adults. Like other arthropods, spiders have to molt to grow as their cuticle (“skin”) cannot stretch. In Most spiders live for only one to two years, although some tarantulas can live in captivity for over 20 years.

Types of Spider Webs

There are a few types of spider webs found in the wild, and many spiders are classified by the webs they weave. Different types of spider webs include:

Funnel webs: with associations divided into primitive and modern.

Spiral orb webs: associated primarily with the family Araneidae, as well as Tetragnathidae and Uloboridae.

Tangle webs or cobwebs: associated with the family Theridiidae.

Tubular webs: which run up the bases of trees or along the ground.

Sheet webs: Several different types of silk may be used in web construction, including a “sticky” capture silk and “fluffy” capture silk, depending on the type of spider. Webs may be in a vertical plane (most orb webs), a horizontal plane (sheet webs), or at any angle in between.

Role of Spiders in the Ecosystem

Arachnids are important albeit a poorly studied group of arthropods that play a significant role in the regulation of other invertebrate populations in most ecosystems (Russell-Smith, 1999). Spiders, which globally include about 42,055 described species (Patel, 2003b; Platnick, 2011), are estimated to be around 60,000-170,000 species. They include a significant portion of the terrestrial arthropod diversity, being one of the dominant macroinvertebrate predator groups in terrestrial environments (35–95%) (Specht and Dondale, 1960; Tikader, 1980).

They occupy a wide range of spatial and temporal niches, exhibit taxon and guild responses to environmental change, extreme sensitivity to small changes in habitat structure, primarily vegetation complexity and microclimate characteristics (Uetz, 1991). Furthermore, strong associations exist between plant architecture and species that capture prey without webs (Uetz, 1991). Spiders respond distinctly to altered litter depth, and structural complexity and nutrient content of litter (Uetz, 1991). They employ a remarkable variety of predation strategies. As they are generalist predators, they are of immense economic importance to man because of their ability to suppress pest abundance in agroecosystems. The population densities and species abundance of spider communities in agricultural fields can be as high as that in natural ecosystems.

In spite of this, they have not been treated as an important biological control agent since very little is known about the ecological role of spiders in pest control (Srinivasulu et al., 2008). Spiders regulate decomposer populations (Clarke and Grant, 1968) and by doing so, they influence ecosystem functioning. Their high biomass also makes them a critical resource for larger forest predators such as salamanders, small mammals, and birds. Spiders can be used as successful biological indicators to assess the ‘health’ of an ecosystem because they can be easily identified and are differentially responsive to natural and anthropogenic disturbances (Srinivasulu et al., 2008). For a species to be identified as an effective ecological indicator, it must meet the primary criteria of being feasible and cost effective to sample, easily and reliably identified, functionally significant, and ability to respond to a disturbance in a consistent manner. Spiders readily meet the first three criteria. Their high relative abundance, ease of collection, and diversity in habitat preferences and foraging strategies allow for effective monitoring of site differences. Many studies have widely recommended the potential of spiders as bio-indicators.

Threats and Conservation

Anthropogenic impacts on spider diversity have been well documented. Factors including habitat loss and degradation, habitat fragmentation, grazing regimes, pollution and pesticides severely affect the spider populations. Introduced exotic species threaten spider populations directly through predation or indirectly by degrading their habitats (Fridell, 1995). Some larger species are further impacted by collection for the pet trade (Leech et al., 1994). Spiders are marginalized when it comes to mainstream conservation research and action. Despite their documented ecological role in many ecosystems, high diversity, and threats, spiders have received little attention from the conservation community (Skerl, 1999). This lack of attention was further compounded by the generally negative public attitude towards spiders (Srinivasulu et al., 2004a), and a paucity of information on spider status and distribution. Additionally, the most critical and useful habitat association data is not found in most checklists. Such data are lacking for many spider species, particularly those with cryptic habits. However, it was important that these vulnerable species are not left out of conservation planning efforts, as they may have unique ecological requirements or require particular site selection and management activities. Preservation of spider biodiversity and better land management strategy design requires an understanding of the patterns of spider diversity on an appropriate regional scale (Prószyński, 2013).

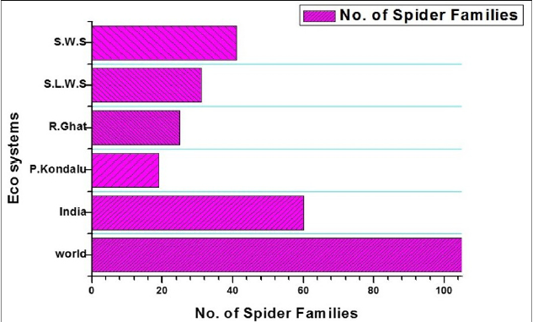

Figure 2: Comparison of spider families of four study sites in Andhra Pradesh with respect to spider families in India and world

Table 3: Diversity indices of spider families from four study sites

|

Diversity indices |

Pallakondalu hills |

Rapur Ghat forest |

Sri lankamala wildlife Sanctuary |

Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve |

|

Taxa (Family) |

19 |

25 |

31 |

41 |

|

Dominance_D |

0.05263 |

0.04 |

0.03226 |

0.04213 |

|

Shannon_H |

2.944 |

3.219 |

3.434 |

3.921 |

|

Simpson_1-D |

0.9474 |

0.96 |

0.9677 |

1.231 |

Justification of Study

The Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh spider fauna (Table 2, Figure 2) was diverse, but effective conservation was impeded by lack of taxonomic knowledge. Few comprehensive works on spiders have been conducted in Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve region of the Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh. As such, conservation of spiders on an appropriate regional scale was necessary. Considering their role in the ecosystem, the present study has been proposed to describe the spider biodiversity in Seshachalam Biosphere Reserve. This study attempts to make an inventory of the spider species in different sites of the Biosphere Reserve with respect to the altitudinal gradient. It also emphasizes the need for conservation of spider biodiversity by characterizing species diversity and highlighting rare and endemic species of Biosphere Reserve. This systematic approach will help to pave the way for better understanding of the Seshachalam spider biodiversity, leading to improvised long term ecological monitoring of the environment that was able to detect the more subtle environmental changes associated with human impact, consumption, and climate change.

Results and Conclusion

Spider diversity (Table 2, Figure 2) representing a total of 19 (6.64%) from Pallakondalu hills, 25 (8.74%) from Rapur Ghat forest and 31 (10.84%) from Sri lankamala wildlife Sanctuary were recorded, which represent 41 (14.34%) from Sri Lankamala wildlife Sanctuary (Kadapa), 6.64% from Rapur Ghat forest area (Nellore) and 14.34% from Southern Tropical Thorn Forest ecosystem of Seshachalam reserve forest compared to Indian mainland with 60 spider families (Table 2, Figure 3). The statistical and diversity indices values for given in Table 3.

The present study was an attempt to compare the current spider fauna from three study sites of Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh in view of previous reports published by Bubesh Gupta (2013), of the 14 families of spiders described by Tirumala from Andhra Pradesh, 18 families have been newly reported in our studies. However, one family viz., Nephilidae has been reported only from Sri Lankamala wildlife Sanctuary region in our investigation.

With an inventory of only one year, we could record 53.33% of spider families, which was comparatively high. This indicates that the spider diversity from the Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh needs further long-term detailed studies using some additional methodologies. The higher number of spider families at Southern Tropical Thorn Forest indicates its faunal significance. At a time when all these ecosystems are experiencing a lot of anthropogenic disturbances, our study emphasizes the urgent need to conserve all these ecosystems. Spiders are well documented as potential bio-indicators in various ecosystems and their role in the dynamics of insect pest population control was well known, therefore, spiders can be used in designing a future Biological Monitoring Program (BMP). Our current and future initiatives encompass, usage of data derived from above investigation to build a spider database for holding information regarding distribution and diversity of these species from Eastern Ghats of Southern Andhra Pradesh.

Acknowledgement

The Corresponding author Dr. S.P. Venkata Ramana, Assistant Professor, Department of Zoology, Yogi Vemana University greatly acknowledge to UGC, New Delhi for financial support through a major research project and also sincere thanks to Andhra Pradesh forest department for giving permission to periodical survey in the forest field areas.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the work.

Author’s Contribution

The first and second authors collected the Spider fauna data and conducted experiments in the laboratory. The third and corresponding author prepared and formatted the manuscript.

References