Effect of Location on Physico-Chemical Composition and Storage Duration of Sweet Orange (Blood Red)

Effect of Location on Physico-Chemical Composition and Storage Duration of Sweet Orange (Blood Red)

Aurang Zeb, Abdur Rab and Shujaat Ali*

Department of Horticulture Faculty of Crop Production Sciences, University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | The lab experiment was conducted on “Effect of location on physico-chemical composition and storage duration of Sweet orange” at The University of Agriculture, Peshawar in 2016. Complete Randomized Design and three replications were used. Sweet orange was collected from four different locations i.e. location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner), location-2 (Rabat, Lower Dir), location-3 (Wartair, Malakand) and location-4 (Palai, Malakand) stored up to 48 days at room temperature, Data was recorded after 12 days of intervals. All the studied parameters were found significantly affected by both the factors i.e. storage duration and locations. The results revealed that the maximum fruit weight loss (16.37 %) was recorded from Wartair (Malakand). The percent weight loss increases with increase in storage duration. The highest fruit Firmness (.6.33 kgcm-2) was observed in location Rabat (Lower Dir) at zero-day storage, the maximum TSS (10.80 oBrix) was recorded from Torwarsak (Buner) at 48-days storage. Ascorbic acid content showed decreasing throughout the storage. The data regarding percent disease incidence revealed that the highest disease incidence (26.66 %) was recorded from Torwarsak (Buner) 48 days of storage freshly harvested fruits. It is concluded that Sweet orange fruits from different locations can be best stored at room temperature (20±1 0C with relative humidity of 45-50 %).

Received | October 14, 2019; Accepted | January 30, 2020; Published | June 15, 2020

*Correspondence | Shujaat Ali, Department of Horticulture Faculty of Crop Production Sciences, University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; Email: shujat.swati@gmail.com

Citation | Zeb, A., A. Rab and S. Ali. 2020. Effect of location on physico-chemical composition and storage duration of sweet orange (Blood red). Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Research, 33(2): 316-320.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.pjar/2020/33.2.316.320

Keywords | Locations, Physico-chemical composition, Room temperature, Sweet orange, Storage duration

Introduction

Citrus is belong to the largest Rosacea family, being grown in Pakistan on an area of 0.19904 million hectares, producing 2.2945 million tons annually, sweet oranges (Citrus sinensis). is a dominant of citrus. The Oranges are native to south East Asia and were cultivated on large scale in China by 2500 BC (Nicolosi et al., 2000), then the sweet oranges referred to as ‘’Chinese’’ apple (Ehler, 2011).

Nowadays, Blood Red oranges having attractive shade on skin and their demand increases from February onwards with increase in prices due to deep red to purplish-pigmented pulp with special delightful aroma that makes the commodity in great demand in country and as a potential candidate for export. Pakistan exported 96540 tons during 2007– 08 (GOP, 2009).

Sweet orange cultivated throughout the world and paly vital role in human’s diet because their high nutritional values and a good source of vitamins and others component i.e. magnesium, calcium, folacin, niacin, potassium, thiamine, (Salunkhe, 1973). Quality of citrus like other fresh fruits depends on its external (Colour and firmness) and chemical component i.e., total acid, total soluble solids / acid ratio and juice content, Total Soluble Solids (TSS) or Brix characters (Sudheer, 2007). Unfortunately, Poor post-harvest handling, storage conditions and climate factor can affect on the content of major groups of fruits and vegetable antioxidants namely; Ascorbic acid (Kalt, 2005). Citrus fruits for example are known for their high ascorbic acid content and other chemical component is more susceptible to significant losses during post-harvest handling and storage (Kalt, 2005).

Keeping in view the importance to increase the post-harvest life of sweet oranges. The present study was planned to ascertain to evaluate the effect different locations on Physico- chemical composition of sweet oranges cultivars “Blood Red” and storage duration in Pakistan is related to human health.

Materials and Methods

The research work entitled “Effect of location on Physico-chemical composition and storage duration of Sweet orange” was conducted in Post-harvest Laboratory at Horticulture Department, UAP during the year 2016. The sweet orange cultivar was selected to this experiment . The sweet orange was collected from four locations i.e. Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner), Location-2 (Rabat, Lower Dir), Location-3 (Wartair, Malakand) and Location-4 (Palai, Malakand) of same cultivar (Blood Red) and washed with tap water. The data were collected every 12th day intervals. While Complete Randomized Design (CRD) having three replications. Three fruits were taken from each treatment for quality analysis.

| Factor A= Locations | Factor B=Storage duration (days) |

|

L1= Torwarsak (Buner) |

D1=0 |

|

L2= Rabat (Lower Dir) |

D2=12 |

|

L3= Wartair (Malakand) |

D3=24 |

|

L4= Palai (Malakand) |

D4=36 |

|

D5=48 |

Study parameters

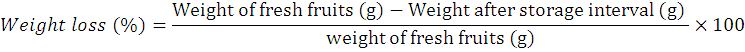

Weight loss (%): Electric balance was used for determining the weight loss of sweet orange. The weight loss was calculated by AOAC (1994) standard method.

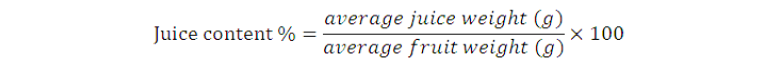

Fruit juice content (%): Fruit juice content was recorded by the procedure given by Rehman et al., (2007).

Fruit firmness (kgcm-2): Fruit firmness was determined with the help of digital Penetrometer. (Model-Wagner FT-327, capacity 28. lbs.).

Total soluble solids (0Brix): Hand Refractometer apparatus was used for determination of TSS.

Ascorbic acid content (mg/100ml): Ascorbic acid content was investigated by titration method AOAC (1990).

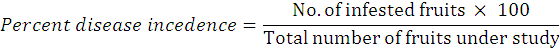

Disease incidence (%): Disease incidence was recorded of all location’s fruits by visual observations at every 12 days of storage duration.

The data recorded were subjected to analysis of variance technique using statistical software STATISTICS 8.1 (Steel et al., 1997 ).

Results and Discussion

Fruit weight loss

The effect of location on Physico -chemical component and storage condition of sweet orang is shown (Table 1). The maximum fruit weight loss (16.37%) was investigated in Location-3 (Wartair, Malakand) which was statistically at par with fruit weight loss (15.98%) observed in Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner), While minimum fruit weight losses (11.13%) was recorded in Location-4 (Palai, Malakand). In case of storage intervals, the weight loss (%) increases with increased in storage duration. The maximum losses (28.12%) of sweet orange was recorded after 48th days storage, which was followed by weight losses (20.22%) in fruit stored up to 36th days. While, zero percent weight loss was recorded in freshly harvested fruit.

Fruit firmness

Similarly, the maximum fruit firmness (5.41 kg cm-2) was recorded in Location-2 (Rabat, Lower Dir), followed by fruit firmness (3.95 kg cm-2) in Location-3 (Wartair, Malakand). While, the minimum fruit firmness (3.72 kg cm-2) was documented in Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner). In case of storage duration, the fruit firmness decreased with increase in storage duration. The highest fruit firmness (5.06 kg cm-2) was recorded from the first day of storage, followed by fruit firmness (4.77 kg cm-2) up to12th day of storage. On the 48th days of storage, the least fruit firmness (3.13 kg cm-2) was recorded.

Total soluble solid

Likewise, the average values of location revealed that maximum total soluble solid (9.85 0Brix) was recorded in Location-4 (Palai, Malakand), which was statistically identical with total soluble solid (9.81 0Brix) observed in Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner). While, the minimum total soluble solid (9.21 0Brix) was recorded in Location-2 (Rabat, Lower Dir). In case of storage durations, the total soluble solids (0Brix) of fruits showed increasing trend with storage duration in Table 1.

Ascorbic acid content (mg/100ml)

The Ascorbic acid content (mg/100ml) loss increased (43.08 mg/100ml) in Location-4 (Palai, Malakand), followed by (36.98 mg/100ml) in Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner) and Location-2 (Rabat, Lower Dir) respectively. However, the minimum ascorbic acid content (34.93mg/100ml) was observed in Location-3 (Wartair, Malakand). Similarly, in storage durations, the increased trend was recorded from the up to the end storage in Table 1.

Disease incidence (%)

Location significantly influenced the disease incidence in sweet orange. The maximum percent disease incidence (13.87%) was recorded in Location-1 (Torwarsak, Buner) (Table 1). While the least percent disease incidence (6.93%) was observed in Location-4 (Palai, Malakand). However, percent disease incidence in fruits increased with storage duration. The highest percent disease incidence (21.0%) was observed in fruit stored for 48th days, followed by while, no incidence of disease (0.00%) were observed in fresh harvested fruits of sweet orange.

The Fruit weight loss (%) increase with storage intervals. When the storage duration increases the moisture and weight loss content in fruits also increases due to water loss and respiration, which reduce the visual appearance, cause turgor pressure and later on the fruit become soft (Ghafir et al., 2009). The decreased in fruit weight due to the loss of moisture (Jan et al., 2012). Ali et al. (2017) also investigated decreasing trend physiological weight loss in different potato cultivars during 90 days of storage at 15 days interval. Fruit firmness is important feature that affects the consumer acceptance of freshly harvested fruits and associated with water content and metabolic variations (Rojas-Grau et al., 2008). The variation in fruit firmness across various location might be due variation in temperature, rainfall and humidity which effect plant performance, water and nutrients availability and ultimately the fruit quality. These results are supported by Reddy et al. (2012) who studied the impact of climatic variation on fruit firmness. The analysis of total soluble solids of during storage reveals a general tendency of increase in soluble solids as the fruits develop to ripening and senescence (Nawaz, 1971). The increase in total soluble solids might be because of the transformation of starch into sugars or might be due to less moisture content or the accumulation of soluble solids due to moisture loss (Rab et al., 2012 ). The increase in sugar content of juice during storage could be due to hydrolysis of cell wall (Tariq et al., 2001). The development of physiological fruit disorders in citrus is greatly influenced by the environment (Austin, 1999). The results are further supported by Wicklow (1995) who observed high incidence of fruit diseases in storage condition. Increase in storage duration also enhances the occurrence of disease in fruits (D’hallewin and Schirra, 2000). The ascorbic acid content decreases with increase in the shelf life after harvest of fruits. According to (Ishaq et al., 2009) the decrease in ascorbic acid content during storage might be due to the transformation of dehydroascorbic acid to diketogulonic acid by oxidation. One of the most important components of citrus and other fruits is ascorbic acid (Gupta et al., 2000) and is quickly used during storage (Kaul and Saini, 2000). The ascorbic acid content of sweet orange as affected by storage duration which may have decreased the rate of respiration (Petracek et al., 1998). The development of physiological fruit disorders in citrus is greatly influenced by the environment (Austin, 1999). The results are further supported by Wicklow (1995) who observed high incidence of fruit diseases in storage condition. Increase in storage duration also enhances the occurrence of disease in fruits (D’hallewin and Schirra, 2000). The variation in disease incidence in sweet orange fruits across of different location might be attributed to climatic condition that in turn effect pathogen development and survival rates (Coakley et al., 1999).

Table 1: Physio- chemical properties of sweet orange fruit as influenced by location and storage durations.

| Storage duration | Weight loss (%) | Fruit firmness (kg cm-2) | Total soluble solids (0Brix) | Vit. C (mg/100ml) | Disease incidence |

| 0 | 0.00 e | 5.06 a | 8.50 e | 50.82a | 0.00 ad |

| 12 | 6.23 d | 4.77 b | 9.00 d | 43.61b | 2.33 d |

| 24 | 14.26 c | 4.35 c | 9.68 c | 37.76c | 8.67 c |

| 36 | 20.22 b | 3.93 d | 10.06 b | 31.19d | 15.00 b |

| 48 | 28.12 a | 3.13 e | 10.58 a | 25.58c | 21.00 a |

| LSD | 0.54 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.88 | 4.45 |

| Locations | |||||

|

L1 |

15.98 a | 3.72 c | 9.81 a | 36.98b | 13.87 a |

|

L2 |

11.57 b | 5.41 a | 9.21 c | 36.21b | 9.60 b |

| L3 | 16.38 a | 3.95 b | 9.38 b | 34.93c | 7.20 b |

|

L4 |

11.13 b | 3.92 b | 9.85 a | 43.08a | 6.93 b |

| LSD | 0.48 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.72 | 3.98 |

L1: Torwarsak (Buner); L2: Rabat (Lower Dir); L3: Wartair (Malakand); L4: Palai (Malakand).

Conclusions and Recommendations

The sweet orange juice were taken from different locations of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. The statistical analysis of Physico-chemical of sweet orange with storage duration revealed that results were highly significant of weight loss (%), fruit firmness (kg cm-2), TSS, ascorbic acid, disease Incidence after 36th days in Palai (Malakand) fruits. It is determined that Palai (Malakand) fruits from different locations can be best stored at room temperature (20±1 0C with relative humidity of 45-50 %) for 30 days.

Acknowledgments

I would like to pay my tributes to Abdur Rab , whose dynamic supervision and encouragement made my research work possible. Special thanks are due to my friend Shujaat Ali for their helpful co-operation, consistent encouragement and healthy suggestions throughout my studies.

Authors Contribution

Abdur Rab: Supervised the research. Aurang Zeb: Designed and performed experiments and co- review the analyzed data, wrote the paper.

References

Austin, M., 1999. Pre-harvest factors affecting postharvest quality of citrus fruit. Advances in postharvest diseases and disorders control of citrus fruit. Trivandrum: Res. Signpost. pp.1-34.

Ali, S., R. Abdur, T.A. Jan, T. Hussain, S.A.S. Bacha, B. Zeb and T.H. Khan. 2017. Changes in physio-chemical composition of potato tubers at room storage condition. Sci. Int. (Lahore). 29: 179-183.

AOAC, 1990. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists, 15th ed.’ Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem., Arlington V.A. pp. 1058-1059.

AOAC. 1994. Official methods of analysis. Association of official analytical chemists. 1111 North 19th Street, Suite 20, 16th Edi. Arlington, Virginia, USA. 22209.

Coakley, S.M., H. Scherm and S. Chakraborty. 1999. Climate change and plant disease management. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 37: 399-426. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.399

D’hallewin, G. and M. Schirra. 2000. Structural changes in epicuticular wax and storage response of ‘marsh seedless grapefruits after ethanol dips at 21 and 50° C. IV Int. Conf. Postharvest Sci. 553: 441-442. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2001.553.103

Ehler, S.A., 2011. Citrus and its benefits. J. Bot. 5: 201-207.

Ghafir, S.A., 2009. Physiological and anatomical comparison between four different apple cultivars under cold-storage conditions. Acta Biol. Szeged. 53: 21-26.

GOP. 2009. Agric. statistics of Pakistan, Statistic Div. Islamabad., pp. 98.

Gupta, A., B. Ghuman, V. Thapar and K. Ashok. 2000. Quality changes during non-refrigerated storage of Kinnows. J. Res. Punjab Agric. Univ. 37: 227-231.

Ishaq, S., H.A. Rathore, S. Majeed, S. Awan and S.S.A. Zulfiqar. 2009. The studies on the Physico-chemical and organoleptic characteristics of apricot (Prunus Americana L.) produced in Rawalakot, Azad Jammu and Kashmir during storage. PJN. 8: 856-860. https://doi.org/10.3923/pjn.2009.856.860

Kalt, W., 2005. Effects of production and processing factors on major fruit and vegetable antioxidants. J. Food Sci., 70: R11-R19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb09053.x

Nawaz. R., 1971. Effect of heat on the quality of pectin in mango juice. M.Sc (Hons) thesis, Univ. Agric. Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Nicolosi, E., Z. Deng, A. Gentile, S.M. La, G. Continella and E. Tribulato. 2000. Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 100: 1155-1166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001220051419

Petracek, P.D., H. Dou and S. Pao. 1998. The influence of applied waxes on postharvest physiological behavior and pitting of grapefruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 14: 99-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(98)00018-0

Reddy, B.M.C., 2012. Physiological basis of growth and fruit yield characteristics of tropical and sub-tropical fruits to temperature. Trop. Fruit Tree Spec. Clim. Change. pp. 45.

Rehman, M.M., N. Khan and I. Jan. 2007. Post-harvest losses in tomato crop. Sarhad J. Agric. 23(4):1279-1283.

Rojas-Grau, M.A., M.S. Tapia and O. Martin-Belloso. 2008. Using polysaccharide- based edible Coatings to maintain quality of fresh-cut Fuji apples. LWT 41: 139-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2007.01.009

Salunkhe, D.K., S.K. Pao, G.G. Dull and W.B. Robinson. 1973. Assessment of nutritive value, quality, and stability of cruciferous vegetables during storage and subsequent to processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 4: 1-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408397309527152

Sudheer, K.P. and V. Indira. 2007. Post-harvest technology of horticultural crops, Vol. 7. New India Publishing.

Tariq, M., F. Tahir, A.A. Asi and M. Pervez. 2001. Effect of curing and packaging on damaged citrus fruit quality. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 1: 13-16. https://doi.org/10.3923/jbs.2001.13.16

Wicklow. 1995. Effect of Post-Harvest heat treatment on food quality, surface structure and fungal disease in Valencia oranges. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 34(8): 1182-1190. https://doi.org/10.1071/EA9941183

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?