Evaluating Flock Dynamics, Offtake-rate, and Farmers’ Perception on Benefits of Community Based Breeding Program in Doyogena District, Central Ethiopia

Research Article

Evaluating Flock Dynamics, Offtake-rate, and Farmers’ Perception on Benefits of Community Based Breeding Program in Doyogena District, Central Ethiopia

Addisu Jimma1,2*, Aberra Melesse1, Aynalem Haile3, Tesfaye Getachew3

1School of Animal and Range Sciences, Collage of Agriculture, Hawassa University, P.O. Box 05, Hawassa, Ethiopia; 2Areka Agricultural Research Centre (ARC), P.O. Box 79, Areka, Ethiopia; 3International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, P.O. Box c/o ILRI 5689. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Abstract | The community-based breeding program (CBBP) is currently active in implementing indigenous breed improvement strategies to achieve genetic progress, economic benefits, and livelihood improvements for smallholders in the pioneer sheep breed improvement cooperatives in Ethiopia. Although the Doyogena sheep CBBP is one of the well-performing breeding cooperatives, there is a lack of up-to-date information regarding farmer perspectives on morphological and reproductive changes (such as conformation, coat color, litter size, growth, and lambing interval), socio-economic benefits, off-take, flock structure, and trends since the CBBP started. To address this gap, a study involving 260 randomly selected farmers, with 130 being CBBP members and 130 non-members owning sheep from similar locations, was conducted. The results revealed significant differences (p<0.05) in various aspects between CBBP members and non-members. CBBP participants showed higher numbers of lambs below 3 months, male lambs between 3-6 months, intact males between 6-12 months, breeding rams, mature ewes, and the mean flock size of sheep at the household level. The major routes of sheep entry into the flocks were birth (81%), and purchase (17%). The total number of entries and births was higher (p < 0.05) in CBBP members (284 vs. 240) than in non-members (148 vs. 112). The off-take rate, representing the proportion of sheep exits from the flock, was significantly higher (p<0.05) in CBBP members (36.45%) compared to non-members (17.35%). Factors such as CBBP participation, gender of the household head, age, flock size, and farm land size influenced flock dynamics and off-take rates. The CBBP was attributed to performance improvements in traits such as growth, coat color, litter size, survival, and lambing interval. Moreover, the program had a positive influence on economic benefits, as CBBP members reported higher annual income from sheep-related activities. This income played a crucial role in supporting farmers’ livelihoods, contributing to house maintenance and providing food for households. In conclusion, the study highlights the positive influence of the Doyogena CBBP on farmers’ livelihoods, thus suggesting the need to scale up the program to benefit a broader community.

Keywords | CBBP, Doyogena-sheep, Flock dynamics, Offtake-rate, Performance traits, Scaling up

Received | December 25, 2023; Accepted | February 16, 2024; Published | March 20, 2024

*Correspondence | Addisu Jimma, School of Animal and Range Sciences, Collage of Agriculture, Hawassa University, P.O. Box 05, Hawassa, Ethiopia; Email: [email protected]

Citation | Jimma A, Melesse A, Haile A, Getachew T (2024). Evaluating flock dynamics, offtake-rate, and farmers’ perception on benefits of community based breeding program in doyogena district, Central Ethiopia J. Anim. Health Prod. 12(1): 108-120.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.jahp/2024/12.1.108.120

ISSN | 2308-2801

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Community-based breeding program (CBBP) was initiated in 2009 in Ethiopia, focusing on four distinct sheep breeds: Bonga, Menz, Afar, and Horro. These breeds were selected to represent different agro-ecologies and production systems, as outlined by Haile et al. (2014). The primary objectives of this program were enhancing sheep productivity and income of smallholders. The preliminary evaluation results of the CBBP have revealed several positive outcomes. Mainly, negative selection has been inverted, breeding rams are retained within the community flock, control mating practices have been adopted, and contributing to improvements in performance traits. Moreover, the selling of selected rams has been carried out at prices higher than the local market, indicating economic benefits for the participants (Haile et al., 2014).

In addition to the core breeding activities, the program has integrated complementary initiatives. These include the introduction of improved forages and feeding options, disease management strategies, and the application of biotechnology tools such as artificial insemination. Furthermore, efforts have been made to facilitate better market access for breeding rams and fattened sheep. Various studies and reports, including those by Rekik et al. (2016), Esayas and Jane (2019), Kassie (2019), and Jane (2019), have documented the design and implementation of these comprehensive activities, contributing to the overall success of the community-based breeding program in Ethiopia.

The community-based breeding program (CBBP) for Doyogena sheep has been actively underway in the Kembata Zone of the Central Ethiopia region since 2013. This program builds upon the promising outcomes observed in previous CBBPs. Evaluation studies, which specifically focused on genetic gain, genetic progress, and the phenotypic performance of growth and some reproductive traits in Doyogena sheep, have shown prominent improvements (Addisu et al., 2021; Kebede et al., 2020, 2022). The documented achievements, as presented in various workshops (https://cgspacecgiar.org/ handle/ 10568/92538), further highlighted the success of the program. These positive developments have driven Doyogena CBBP into a phase of significant progress, attracting attention from institutions that are working on small ruminants.

The success or failure of any genetic improvement program depends on the intuitive knowledge of farmers (Kosgey et al., 2006). However, to achieve successful outcomes, it is important to incorporate participatory implementation supported by empirical data. The implementation process, technical and socioeconomic evaluations for first generation CBBPs, particularly for Bonga, Menz and Horro sheep have been conducted with the participation of sheep producers (Gutu et al., 2015, Haile et al., 2020). However, such information are lacking for Doyogena CBBPs. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to assess flock dynamics, explore farmers’ perceptions regarding morphological and reproductive changes in sheep, examine the socio-economic benefits, and identify constraints associated with Doyogena sheep CBBPs.

Materials and Methods

Description of the study area

The study was conducted at Doyogena district, Kembata Zone in the Central Ethiopia Region. The Doyogena district is situated at 70 20’ N latitude and 370 50’ E longitudes. The altitude ranges from 1900 to 2800 meters above sea level. The mean average annual rainfall is between 1200 and 1600 mm with an average mean temperature of 10 – 16 °C. Enset (Ensete ventricosum) based mixed crop-livestock production system is the dominating production system in the study area (Taye et al., 2016), which is entirely dependent on rainfall. Cattle, sheep, poultry, equine and goats are the major livestock species kept in the district.

Description of the breeding program and breeder cooperatives

For this study, five sheep breeder cooperatives implementing community-based breeding program (CBBP) in Doyogena district, Kembata Zone were randomly selected from the existing eight cooperatives. The five selected CBBPs included Anicha-Sadicho, Murasa-Woyiramo, Hawora-Arara, Serera-Bukata and Lemi-Suticho, all of which have been implementing CBBPs since 2013. The main objective of the breed improvement program is to increase the income of households through enhanced lamb growth, reduced mortality and increased number of lambs born per breeding ewe. The major criteria for enrollment as CBBP member include sheep holding and willingness to pay membership fee (110 ETB). The CBBP has a bylaw that includes paying a membership share, which is 50 ETB, and each member can buy 10-20 shares, contributing at least two breeding ewes, practicing good sheep management, and communicating with enumerators for data collection at different growth stages of the lambs.

Enumerators were hired by the former Southern Regional Bureau of Agriculture for data collection when various events occur. Participant farmers keep newly born lambs until the selection period (six-month age) and bring the animals to the central place for selection to identify the best rams. A team of researchers and selection committee members have been involved in the selection process. Based on growth performance, estimated breeding value (EBV), and breeding objectives, the top 10% of rams have been selected. These rams were purchased by the cooperatives and used to mate ewes, with about 20-30 organized in a mating group under cooperative members.

Sources and procedures of data collection

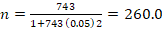

Two sources of data were used for the study: primary and secondary. Primary data was captured through interviews, field observations, group discussions and monitoring animals from December 2021 to November 2022. A semi-structured pre-tested questionnaire was prepared for the formal survey. One group with 8-12 members was organized for group discussion in each cooperative. The discussion was focused on farmers’ perception towards the breeding program, lessons/knowledge acquired during the breeding program, sustainability and suitability of the program, flock management and problems encountered. Data focusing on-flock size and structure, keeping breeding ram and mating system, flock dynamics (incoming and exiting routes of sheep), biological changes such as growth, conformation, survival, litter size, and coat color that farmers have recognized. In addition, change on income from sheep and its contribution to livelihood, and constraints they have faced along with socio-economic characteristics were also collected through formal survey and used as a primary source. Recorded data (number of animal selected, sold animal number and price of selling, members of cooperatives) were obtained from the secondary source and other additional information collected from cooperative’s receipts, invoices, record books and case histories. Among total sheep producers in the study site, a total of 260 sheep producer households were included in the study, from which 130 respondents were selected to represent 358 CBBP members while the rest, 130 respondents were selected from non-CBBP members by using the simple random sampling technique based on probability proportional, following Yamane’s (1967) formula:

Where: n= sample size for the study; N= Total number of sheep producers (743) from selected sites and e is level of precision which was taken to be 5%.

Data analysis

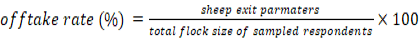

The collected data were entered into an Excel sheet and checked before analysis. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS, 2012) was used for the analysis of the collected data. Descriptive statistics, including means, frequency, and percentile for flock size, flock dynamics, and benefits of sheep (trend of selected rams, CBBP member participation, income, and price of ram per kilogram weight), were conducted. Independent t-tests were carried out to compare quantitative variables, including flock size and structure, and income from sheep, between CBBP members and non-members. Indices were employed to calculate the traits improved through selection, to assess sustainability mechanisms, and constraints of Doyogena CBBP using method mentioned by Kosgey (2004). To obtain the sheep offtake rate, each parameter was calculated using the methods employed by Shigdaf et al. (2012) and Deribe et al. (2021).

Sheep exit parameters (routes of sheep leaving mechanisms from the flock) are sale, slaughter, gift and shareholding-out.

The Poisson regression model was employed to assess the factors influencing flock dynamics, and the income obtained from sheep. Socio-economic characteristics of the respondents, such as , gender, age, education, family size, , and farm land size, were hypothesized to positively or negatively influence the response variables (routes of sheep entry into and exit from the flock, and income) along with CBBP participation and flock size. The Poisson regression model was chosen for the analysis of count data due to its suitability. It can be estimated using the quasi-maximum likelihood approach and can address issues related to over-dispersion (Dubale and Yohannis, 2021; Verbeek, 2004).The model used for Poisson regression is as follows:

Log (y) =β0 + β1x1+β2x2+ β3x3+ β4x4+β5x5 + β6x6+β7x7

Where log(y) is logarithm of predicated mean number of response variables (income, way of sheep entry to the flock and exit from the flock); y is the mean of the response variable, β0 is intercept; β1, β2, β3, β4, β5, β6 and β7 are the coefficients to be estimated. The coefficients represent the change in the logarithm of the expected value of the dependent variable for a one-unit change in each independent variable, holding other variables constant.

Independent variables are CBBP with levels participation level (1=member, 2= non-member), sex of respondent household head (1=male, 2=female), education (1=illiterate, 2= primary and above), age (in number), farm land size (in hectare), family size (in number), flock size (in number).

Results and Discussion

Flock structure and dynamics

Flock structure: The least-square means (SE) of sheep composition per household in the Doyogena district are presented in Table 1. Overall flock size per household in the Doyogena district was 3.84, ranging from 1-14 heads. The castrated sheep had the smallest percentage in the flock, with 1.3%, the higher proportion was recorded for breeding ewes (48.43%) followed by intact males aged 6 to 12 months (15.36%).

Male and female lambs aged 3-6 months made up 7.03% and 5.73% of the total, respectively. The mean number of young lambs below 3 months of age , male lambs aged 3-6 months, intact male aged 6-12 months, female lambs aged 6-12 months, breeding rams, breeding ewes, and the number of lambs per household were higher (p<0.05) in CBBP members compared to non-members.

The distribution of flock structure reflects the management choices made by producers, based on their production goals (Solomon et al., 2010). At the CBBP level, keeping fast-growing lambs has reduced lamb mortality while increasing litter sizes, resulting in significant improvements in flock structure and size (Haile et al., 2014; 2020). In the present study, the average flock size was lower than the values reported by Tibbo et al. (2006) for Bonga (11.3), Horro sheep (8.2), and that of Abebe (1999) for Menz sheep. However, it was comparable to that of Taye (2016), reported in the same study district. The shortage of land for grazing could be one of the reasons for the low flock size in the study area. Gutu et al. (2015) have reported that the flock size of sheep for CBBP member households was higher than non-member households for Bonga, Horro, and Menz sheep, which was similar to the current study. The higher proportion of breeding ewes in the flock is an opportunity for a high number of lamb productions and the need for sustainable household income in the study district. The finding is comparable to the findings reported by Luke (2010), Shenkute et al. (2010), Tasew et al. (2014), and Amare et al. (2019). According to the bylaw of the cooperatives every CBBP member is expected to keep at least two breeding ewes with a good maternal record for genetic improvement for the next generation.

The proportion of intact ram aged 6-12 months was higher than from all except breeding ewes. The reason could be in the CBBPs, keeping male lambs until selection is mandatory and which increase the possibility of getting best-performing animals to be parents for the next generation. In some cases, CBBP members keep selected lambs that were 2–6 months after selection until they get a better market. Retaining breeding ewes and keeping male lambs until selection would enhance selection intensity and improves genetic progress (Haile et al., 2020).

The breeding ram to ewes ration in the study site was 1:24, and farmers practiced year-round breeding with control mating. This practice is attributed to the presence of CBBP. Intensive selection of breeding rams, combined with the acquisition of knowledge by CBBP members through participatory training and direct program involvement, could positively contribute to the success. Our findings are consistent with a similar report by Asrat et al. (2021) for Bonga sheep (25 to 30 breeding ewes), and that the current study ratio is higher than that reported by Aynalem (2021) for Horro sheep (1 to 6.34) at the CBBP.

Flock dynamics and offtake rate: Table 2 shows the flock dynamics and offtake for the Doyogena district. In our study, we identified the major ways through which sheep enter and leave the flock in the study area. The primary methods of sheep entering flocks include the birth of lambs, gifts, shareholding-in (keeping animals for the benefit share obtained from those with a larger flock size), and purchases.

In the Doyogena district, both CBBP member and non-member households indicated that sheep entered flocks more frequently through birth (Table 2). Total entry was significantly affected by CBBP membership. Similarly, membership exerted significant difference only on birth and shareholding-in among routes of entry. In the study district, 352 lambs were born during the 12-month period from December 2021 to November 2022. Of all entries, birth accounted the highest proportion of entry, with 240 (84.51%) lambs for CBBP members and 112 (75.68%) lambs for non-members. Additionally, the cooperatives acquired 39 (13.73%), 4 (1.41%), and 1 (0.35%) through purchasing, shareholding and gift, respectively. Similarly, 36 (24.32%) were entered through purchases for non-members. Parallel to the current study, Kocho et al. (2011) and Deribe et al. (2014) reported that the primary route of entry for sheep in the Alaba zone of southern Ethiopia was birth. The authors’ reports demonstrated that shareholding is an essential method of strengthening the flock within the sheep farming community, consistent with the present study.

The exit routes vary widely among members and non-members. CBBP members had significantly higher (p < 0.05) sheep exiting through sale, slaughter, and shareholding compared to non-members. Out of a 401 and 187 sheep flock, approximately 59% and 75% of sheep left the flock due to sale in CBBP member and non-CBBP member households, respectively. The reason of higher proportion of sheep sale in non-member is that there is no binding rule that can prevent early sales, which could be a potential reason for negative selection in the flock. On the other hand, the cooperative bylaw encourages producers to keep the best-performing animals. Animals with low performance have exited the flock through sale. Reports of other studies confirm that the sale was the major exit route for sheep in central Ethiopia (Legesse et al., 2008; Kocho et al., 2011).

Gift and shareholding as an exit route accounted for 7.9 and 1.49% for CBBP members, respectively, while it was minimal for non-members.

The overall off-take rate for Doyogena sheep was 53% (Table 2). The members of the CBBP in the study district exhibited a higher off-take rate at 36%, in contrast to non-cooperative members at 17%. This higher off-take rate in the breed improvement cooperative can be attributed to the strategic culling of unproductive animals, the implementation of fattening practices tailored for festivals, disseminating improved rams, and collaboration within the group leading to improved market opportunities. In contrast, non-participants tended to sale animals at younger ages, aligning with findings from Deribe et al. (2021) and Kocho et al. (2011), who noted that in Alaba district, sheep and goat keepers sold their animals before reaching breeding age. The off-take rate (53.8%) in this study is higher than other research endeavors. For instance, CSA (2020) reported an off-take rate of 30.8%, while Shigdaf et al. (2012) documented rates of 25.3% and 32.8% for sheep in Farta and Lay Giant districts, respectively. Furthermore, the percentage of sheep sales (18.7%) and slaughter (11.3%) reported by CSA (2020) was comparatively lower and consistent with our findings, respectively.

Factors affecting dynamics of sheep entry routes: The CBBP participation, sex of the household heads, and flock sizes were found to influence the sheep entry routes (Table 3). The study revealed that the participation in the CBBP significantly (p<0.01) influenced the entry routes of sheep into households. Particularly, farmers engaged in the CBBP demonstrated a significant positive correlation with the birth of lambs, indicating that program participants experienced a 44% increase in the number of animals entering their flocks through birth compared to non-participants. This suggests that the CBBP plays a vital role in enhancing the reproductive outcomes within the sheep breeding cooperatives. Additionally, the study highlights the influence of flock sizes on sheep entry routes, showing that farmers with larger flocks are more likely (p<0.001) to accept animals through birth, with a 21% higher tendency compared to those with smaller flocks. This finding shows the importance of flock size management in optimizing sheep breeding outcomes.

Furthermore, the study identified the sex of household heads as a determinant factor in sheep acquisition patterns. Specifically, households with male heads are less likely to accept animals as gifts or for shareholding. This observation may be attributed to cultural or gender-specific roles and preferences within the community. Additionally, the household heads those who have smaller family sizes are less inclined to purchase sheep, with a significant association to the scarcity of labor. This aligns with existing literature, such as reports by Legesse et al. (2008) and Budisatria et al. (2007), who indicated that labor shortages can be a limiting factor in small-scale livestock keeping, particularly in contexts where family members are essential contributors to farming activities.

Factors affecting dynamics of sheep exit and offtake rate: As shown in Table 4, CBBP participation, gender, age, land size, and flock size of the households were shown to influence the offtake and sheep exit routes. Sheep exit through sale, slaughter, gift, and shareholding-out was significantly (p<0.05) affected by CBBP participation. The animal exits through sale in the CBBP members were significantly (P<0.01) higher and 1.52 times more than non-members. This might be associated with the higher number of sheep produced through birth for the CBBP member households due to the use of different production packages and the existence of breeding cooperatives (Rekik et al., 2016; Esayas and Jane, 2019; Jane, 2019). This ensures better market participation of CBBP members than non-members. Similarly, the number of animals slaughtered for household consumption was also higher (p<0.001) for CBBP members.

The number of slaughtered animals within a year in CBBP members was 2.4 times higher than that in non-members. This result aligns with previous findings by Gutu et al. (2015) and Haile et al. (2020), who reported changes in the number of sheep sold per year and the consumption of mutton as a result of CBBP membership compared to non-CBBP members for Bonga, Horro, and Menz sheep in CBBP sites. The CBBP participation significantly influenced the probability of sheep exit through shareholding and gifting (p < 0.01). This could be attributed to the larger flock size of CBBP members. In Doyogena CBBP, the CBBP members provided for other members of CBBP, particularly those with a small number of sheep for shareholding. This might be advantage to keep better-performing animals in breeding cooperative. Shortage of labor and feed could be the reason for animal exit through shareholding.

The gender of the head of the household exerted a favorable influence on animal sales, with males showing a significantly higher tendency to sale animals compared to households led by women (p < 0.001). This aligns with the findings of Ashenaf et al. (2013), who reported that women are primarily responsible for managing tasks such as feeding, herding, and cleaning, while males take on the role of decision-makers in terms of purchasing and selling sheep. Households led by women frequently accept animals instead of selling them, driven by financial difficulties. Debesa (2020) reported that poor market participation, limited technical skill and financial resources affect the role of women compared to men in small ruminant value chain, which is agree with this study.

Table 1: Least square means (SE) of flock size and percentage of flock structure at CBBP member and non-member.

| Sheep flock composition |

CBBP member |

Non-member |

Overall |

P-value |

|||

| N=130 |

% |

N=130 |

% |

N=260 |

% |

||

| Lambs below 3 months | 0.62 ±0.09 | 13.37 | 0.28±0.05 | 9.3 | 0.45±0.07 | 11.72 | 0.001 |

| Male lambs between 3-6 Mths | 0.460 ±0.07 | 9.85 | 0.24±0.05 | 8 | 0.27±0.06 | 7.03 | 0.01 |

| Female lambs between 3-6 Mths | 0.25 ±0.05 | 5.35 | 0.18±0.04 | 6 | 0.22±0.05 | 5.73 | 0.319 |

| Female lambs between 6-12 Mths | 0.23 ±0.048 | 4.93 | 0.12±0.04 | 4 | 0.18±0.04 | 4.9 | 0.0001 |

| Male lambs between 6-12Mths | 0.81 ±0.09 | 17.34 | 0.38±0.05 | 12.1 | 0.59±0.07 | 15.4 | 0.0001 |

| Breeding rams | 0.11±0.03 | 2.36 | 0.05±0.02 | 1.6 | 0.08±0.03 | 2.9 | 0.02 |

| Breeding ewes | 2.03 ±0.08 | 43.47 | 1.68±0.05 | 56 | 1.86±0.07 | 48.44 | 0.003 |

| Castrated | 0.07±0.027 | 1.49 | 0.02±0.01 | 0.6 | 0.05±0.02 | 1.32 | 0.128 |

| Fattened | 0.09±0.04 | 1.93 | 0.04±0.02 | 1.3 | 0.07±0.03 | 1.82 | 0.187 |

| Overall flock size | 4.67 ±0.20 | 3.0 ±0.08 | 3.84±0.14 | 0.0001 | |||

N =number of respondents; Mths=months

Table 2: The proportion of dynamics and offtake rate of sheep flock (%) in CBBP membership.

|

Parameter |

CBBP-member N=130 |

Non-member N=130 |

Overall N=260 |

χ2 |

|||

| N |

% |

N |

% |

N |

% |

||

| Incoming reason | |||||||

| Birth | 240 | 84.51 | 112 | 75.68 | 352 | 81.48 | 29.893*** |

| Gift-in | 1 | 0.35 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.23 | 1.004 |

| Shareholding-in | 4 | 1.41 | 0 | 0.00 | 4 | 0.93 | 4.062* |

| Purchase | 39 | 13.73 | 36 | 24.32 | 75 | 17.36 | 7.00 |

| Total entry | 284 | 100 | 148 | 100 | 432 | 100 | 30.267*** |

| Exiting reason | |||||||

| Death | 40 | 9.97 | 16 | 8.56 | 56 | 9.52 | 7.028 |

| Sale | 238 | 59.35 | 140 | 74.87 | 378 | 64.29 | 31.64*** |

| Slaughter | 83 | 20.7 | 28 | 14.97 | 111 | 18.88 | 23.0*** |

| Predator | 2 | 0.5 | - | - | 2 | 0.34 | 2 |

| Gift-out | 6 | 1.49 | - | - | 6 |

1.02 |

6 |

| Shareholding out | 32 | 7.98 | 3 | 1.6 | 35 | 5.95 | 12.5* |

| Total exit | 401 | 100 | 187 | 100 | 588 | 100 | 41.12*** |

| Offtake-rate | 359 | 35.97 | 171 | 17.13 | 530 | 53.1 | 42.78*** |

N=number of animals, *, ** and *** the proportion of dynamics b/n CBBP level significant at p <0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively.

Table 3: Coefficients (standard errors) and exponential values of Poisson regression for factors contributing sheep entry routes in Doyogena district.

| Factors |

Birth |

Purchase |

Gift and shareholding in |

|||

| Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

|

| CBBP participation |

0.363(0.13)** |

1.44 | 0.021(0.26) | 1.02 | - | |

| Gender | 0.052(0.12) | 1.05 | -0.318(0.25) | 0.73 |

-1.743(1.03)* |

0.17 |

| Family size | 0.002(0.02) | 1.00 | -0.083(0.05)* | 0.92 | -0.249(0.24) | 0.78 |

| Flock size |

0.187(0.23)*** |

1.21 | 0.058(0.06) | 1.06 | -0.213(0.27) | 0.81 |

| Log likelihood | -372.454 | -193.019 | -18.520 | |||

| Chi- square | 114.891 | 6.676 | 12.433 | |||

*, ** and *** mean coefficient significant at the level of p <0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively

Sales were significantly and negatively affected by the respondents’ ages. This demonstrates that younger individuals are more involved in the production of sheep and sale than the older household head, and it offers young farmers looking for work the chance to take part in sheep breeding. This in line with Ayele et al. (2003), who got negative association between age of households and beef cattle market participation. However, it contrasts the finding of Dubale and Yohannis (2020), who found that the older people were more enthusiastic to participate in sheep market than the younger people. As a result, they sell more number of sheep in the market.

The farmers who have larger farm land size had (p<0.01) higher (1.66 times more) number of animals sale than who have smaller land size. Farm land size also significantly (p<0.01) affected the probability of sheep exiting through death. The study confirm that the report indicated by Terfa (2012), who reported that the number of sheep owned significantly and positively affected the intensity of sheep market participation.

The household with a small land size manages their animals by practice tethering in roadside and land-demarked areas most of the year. The feed shortages in the dry season and drought period are the main reasons of sheep exit through death (Addis, 2015; Habite et al., 2019). The influence of flock size was positive on the sale of animals, slaughter, death, and shareholding-out. Farmers with a larger flock size tended to sale a greater number (p<0.001) of animals and likewise had a higher (p<0.001) probability of slaughtering sheep for home consumption. This agrees with the finding reported by Mapiliyao et al. (2012).

Farmers’ perception on benefits of Doyogena sheep CBBP

Trend of Doyogena CBBP and socio economic benefits

The Doyogena Community-Based Breeding Program (CBBP) has shown significant enhancements in various key indicators between 2014 and 2022. These findings collectively indicate positive trends and progress in the Doyogena CBBP. The growth in the number of selected rams (from 56 to 357; Figure 1) and participants (from 35 to 276; Figure 2) shows increasing engagement and interest in the program. The substantial increase in income, from ETB 474,000 (USD 24,126.60) to ETB 3,398,203 (USD 70,958.51) through ram sales (Figure 3), along with the rise in the price per kilogram of live weight (increasing from 70 to 180; Figure 4), further underscores the economic success and viability of the program throughout the studied period. These improvements underscore the positive influence of the Doyogena CBBP on the local economy and the livelihoods of program participants.

Note: At the study period (2022) 1USD = 47.89 ETB and at year of 2014 1USD = 19.65ETB

From the total candidate rams, 20% were selected for genetic improvement, with the top 10% reserved for serving ewes of the members and the remaining 10% distributed for genetic improvement outside the CBBP sites. A comparable trend to the current study in various production systems and sheep breeds at the CBBP was reported (Gutu et al., 2015; Haile et al., 2020; Arab et al., 2021; Asrat et al., 2021).

The higher (p < 0.038) number of participants providing breeding rams to the community every year might have contributed to producing more lamb crops through birth, which is vital for genetic improvement in a progressive manner and ensures the participation of members. The CBBP ensures better participation of smallholder farmers in the breed improvement process and rewards them with better benefits (Merkina et al., 2012; Haile et al., 2018; Getachew et al., 2020). The number of CBBP households participating in the scheme has increased from 35 in the year 2014 to 276 in the year 2022. This might be due to the awareness level of farmers because of the multi-stockholder participation on various activities in the CBBP site. According to Markina et al. (2012), a large number of animal owners and increased participants contributed to the success of the program. Moreover, an increase in the membership of CBBP over time was due to improved benefits and the attraction of the scheme (Bhuiyan et al., 2017; Kaumbata et al., 2021; Wurzinger et al., 2021). Similarly, Gutu et al. (2015) and Arab et al. (2021) observed that the number of participant farmers in different CBBPs in Ethiopia showed increasing trends.

Breeding ram’s price was set on weight basis by the CBBP committee members. The price of one-kilogram live weight of elite ram was sold at a prize of ETB 70 in 2014 while it increased (p<0.01) to ETB 180 in 2022. A total income obtained by the sale of breeding rams was increased considerably (p<0.019) from 474,000 ETB (24,126.6 USD) in the year 2014 to 3,398,203 ETB (70,958.51 USD) in 2022 (Figure 4). Each participant farmer earned an average of 7,728 to 12,312 ETB annually. The increment of income from the sale of breeding ram was because of the increase of farmers’ participation providing breeding rams and strategy of community based breed improvement program. In concurrent to the present study, Haile et al. (2023) reported an increase of 20% on average in the previously established CBBP on Horro, Menz and Bonga sheep since 2009.

Factors affecting annual income: Factors affecting the annual income obtained from sheep sales are indicated in Table 5. Income for CBBP members was positive and significantly (p<0.001) higher (over 48%) than that of non-CBBP member households. This might be due to theconsecutive training offered for CBBP participant households on the breed improvement program and flock performance improvement, which have ensured better market participation in selling elite rams and culling nonproductive animals among member farmers than non-members. The findings reported by Kassa et al. (2021) and Areb et al. (2021) for Bonga sheep; Gutu et al. (2015) for Bonga, Horro, and Menz sheep; and Haile et al. (2020) for Bonga and Menz sheep breeding finds similarity with the current study.

The gender of the household head had a positive influence on the yearly income generated from sheep (p < 0.001). This implies that male household heads sell 1.03 times higher number of animals than female household head.

Respondents with lower educational level (illiterate) generated lower income from sale of sheep than those who had attended primary school and above. This due to education improves the knowledge of sheep producers to involve breed improvement activity and sale more number of animals. Kassa et al. (2021) and Areb et al. (2021), for Bonga sheep for breeding reported parallel with our findings.

Table 4: Coefficients (SE) and exponential values of Poisson regression for factors contributing sheep exit routes from the flock in Doyogena district.

| Factors |

Response variables |

|||||||

| Sale |

Slaughter |

Death |

shareholding out |

|||||

| Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

Coef.(SE) |

Exp(B) |

|

| CBBP | 0.417(0.12)** | 1.52 | 0.858(0.24)*** | 2.358 | 0.37(0.34) | 1.449 | 1.863(0.64)** | 6.443 |

| Gender | 0.277(0.02)* | 1.32 | -0.114(0.21) | 0.892 | -0.665(0.30) | 0.514 | 0.266(0.43) | 1.305 |

| Age | -0.019(0.01)** | 0.98 | -0.001(0.01) | 0.999 | 0.002(0.01) | 1.002 | -0.016(0.02) | 0.984 |

| Land size | 0.508(0.18)** | 1.66 | 0.015(0.38) | 1.015 | 0.984(0.46)* | 2.675 | -1.175(0.87) | 0.309 |

| Flock size | 0.073(0.03)** | 1.08 | 0.133(0.42)*** | 1.142 | 0.173(0.06)** | 1.189 | 0.251(0.07)** | 1.285 |

| Log likelihood | -395.676 | -208.089 | -136.150 | -84.800 | ||||

| Chi- square | 64.421 | 39.437 | 25.479 | 39.878 | ||||

*, ** and *** mean coefficient significant at the level of p <0.05, p<0.01 and p<0.001 respectively

Table 5: Factors influencing the annual income generated from sheep sale.

| Parameter |

Coefficient |

Std. Error |

ExP(B) |

P-value |

|

| CBBP participation level | 0.391 | 0.0022 | 1.48 | 0.000 | |

| Gender of household head | 0.026 | 0.0022 | 1.03 | 0.001 | |

| Education | . | . | |||

| Illiterate | 0.016 | 0.0027 | 1.016 | 0.001 | |

|

Primary school |

0.018 | 0.0023 | 1.018 | 0.000 | |

| Age of respondents | -0.010 | 0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.024 | |

| Family size | 0.020 | 0.0004 | 0.98 | 0.002 | |

| Land size | 0.222 | 0.0033 | 1.25 | 0.000 | |

| Flock size | 0.059 | 0.0004 | 1.06 | 0.000 | |

| Log likelihood | -292827.756 | ||||

| Log likelihood ratio chi- square | 98407.947 | ||||

Table 6: Contribution of income obtained from sheep (ETB) on the livelihoods of CBBP and non CBBP member.

|

Sheep income contribution |

Mean ± SD |

P-value |

|||

| N |

Member |

N |

Non-member |

||

| School fee and input | 62 | 1518.2±1259 | 29 | 1396.6±1462.7 | 0.645 |

| Fertilizer for crop production | 58 | 1763.6±1278.4 | 38 | 1765.6 ±1446.2 | 0.606 |

| Improved crop seed | 48 | 1443.8±1081.9 | 28 | 2204.3± 1446.4 | 0.560 |

| House building and maintenance | 25 | 6743.2±5443 | 16 | 2596.9±2471.4 | 0.001 |

| Family cloth | 59 | 1821.4±1317.9 | 33 | 1607.9 ± 1019.8 | 0.425 |

| For home consumption (variety of diet) | 50 | 4309.6±7114.7 | 29 | 1679.3± 1635.38 |

0.040 |

N= number of respondents

Table 7: Traits improved due to selection in the CBBP of Doyogena sheep improvement program.

| Traits improved |

Respondent rank |

Index |

Rank |

|||||

| Rank 1 |

Rank 2 |

Rank 3 |

Rank 4 |

Rank 5 |

Rank 6 |

|||

| Growth | 46 | 40 | 26 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 0.2183 | 1 |

| Color | 24 | 24 | 18 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 0.2065 | 2 |

| Litter size | 21 | 17 | 19 | 40 | 19 | 11 | 0.1613 | 3 |

| Body size | 13 | 25 | 27 | 18 | 23 | 19 | 0.1521 | 4 |

| Survival | 18 | 13 | 14 | 25 | 24 | 30 | 0.1454 | 5 |

| Lambing-interval | 7 | 9 | 25 | 13 | 33 | 37 | 0.1164 |

6 |

Table 8: Sustainability mechanism of Doyogena CBBP mentioned by members.

| Mechanism |

Rank1 |

Rank2 |

Rank3 |

Index |

Rank |

| Promoting cooperatives to Union | 71 | 10 | 27 | 0.403 | 1 |

| Creating credit access from micro-finance | 19 | 48 | 40 | 0.299 | 2 |

| Engaging multi stakeholders to the program | 20 | 47 | 38 | 0.298 |

3 |

Farm land size of the household had significant (p<0.0001) influence on income, and the household head with larger land size generated 1.25 times more income than those having smaller land size. This is because of households with large land size keep large number of animals, subsequently more number of animal offers to sale. The number of sheep in the household’s flock has a significant (p<0.0001) and positive effect on the annual income generated from sheep sales.

Sheep income contribution on the livelihood of the farmers

In the study district, both groups of farmers (CBBP members and non-members) obtained income from sheep, enabling them to spend more on their basic needs and assets, including school expenses for their children, fertilizer and improved crop seed purchase, house building and maintenance, family cloth, and diet diversification. CBBP participants made significant contributions (P < 0.05) to their livelihoods through income obtained from sheep sales (Table 6). For instance, they constructed new house and maintained existing ones for their families. They also used the money to buy dairy cows, providing animal-driven nutrition for family members and enabling slaughtering for home consumption. A report by Kebede et al. (2022) indicated that in the some districts of this study, farmers participating in CBBP benefited from sheep income, allowing them to provide a varied diet for their families and construct houses for both themselves and their animals. In the Alaba zone, farmers used the income obtained from the sale of small ruminants to purchase inputs for crop production, cloth, and the family’s diet, as well as to cover educational expenses for the children (Deribe et al., 2021), which is similar to the findings of this study.

Traits improved due to CBBP interventions

Traits improved due to selection in the CBBP site for Doyogena sheep are shown in Table 7. All respondents among CBBP members perceived that improvements were made in their sheep flock, with the largest impact seen in the growth performance of their sheep (1st). This was followed by improvements in coat color (2nd), litter-size (3rd), body size (4th), survival (5th), and lambing interval (6th).

The majority of respondents indicated that the coat color (light red and dark red) of the sheep was mentioned among improved trait due to the genetic improvement program. This improvement resulted in fetching a better price when selling the sheep due to the buyers’ preference for the specific color. These findings align with those of Areb et al. (2021), who reported that growth and coat color were the most important traits for the CBBP of Bonga sheep. Coat color is among the most influential factors determining sheep prices in the Bonga CBBP (Kassa et al., 2021) and sheep in the highland of northern Ethiopia (Beneberu et al., 2011). In many Ethiopian livestock markets, the color of live animals sold for slaughter plays a significant role due to various cultural and traditional beliefs. The improvement of litter size of Doyogena sheep of the current study in line with the finding, Gutu et al. (2015) reported that a percentage of CBBP members in Bonga (72.5%) and Horro (65%) mostly reported twin births in their ewes. The improvement in litter size may be associated with the selection favoring the trait responsible for multiple births. The enhancement of performance traits, as a result of the best ram selection, controlled mating practices integrated with feeding, and health intervention activities, could be the reason (Mirkena et al., 2012) and (Weldemariam et al., 2020). Moreover, reported evidence indicated that appropriate selection improved performance on growth rate, lambing interval and reduced mortality in all communities of Eastern and Southern Africa (Haile et al., 2023). Hence, selection of elite animals brought improvement on most economical important traits and coat color of the animals.

Sustainability mechanism of Doyogena CBBP

Sustainability options of Doyogena sheep presented in Table 8. To maintain the sustainability of Doyogena CBBP, promoting cooperatives to form unions was the best course of action as reported by the respondents. This was closely followed by equally valuable responses such as setting up a credit facility and interacting with many stakeholders. The study showed that farmers understood working with cooperative or group is acceptable and improves their livelihoods. Community based breeding program is an important tool for effective utilization of genetic resources. Hence, strengthening the breeding cooperatives and promoting the cooperative to union may help to get more credit access, ensure market participation at domestic and international level, improve bargaining power and develop strong stakeholder integration. Other scholars mentioned additional sustainability mechanisms for different CBBPs (Merkina, 2010; Muller et al., 2015; Haile et al., 2018, 2019).

Constraints affecting Doyogena CBBP

Major constraints encountered by the members of the Doyogena CBBP are presented in Table 9 The major constraints mentioned were audit delaying (Index=0.175), the gap in keeping cooperative bylaw (Index=0.15), lack of trust in CBBP leaders (Index=0.139), lack of market demand for higher weighing rams (I=0.1389), aggressiveness of the breeding rams (Index=0.1134), lack of credit access (Index=0.1061), concentrate feed shortage (Index=0.093), and disease (0.0817).

The delay in auditing poses a significant challenge across all breeding cooperatives. In the CBBP, member farmers have the right to receive the results of cooperative audits on a yearly basis and benefit from the profits. Seed money for revolving purposes was provided to all cooperatives during the implementation period. At the beginning cooperative formation, every participant paid a membership fee and share. Farmers pay a 100 birr margin per animal when they sale the selected rams to and out of the community for breeding.

However, in some cooperatives, members were unaware of their cooperative’s financial progress over the last five to six years. The timely replacement of CBBP leaders by a new committee and the lack of interest from the woreda cooperative office in inspecting and auditing periodically were the main problems. The cooperative bylaws formulated during the establishment of CBBP were accepted by all

Table 9:Major challenges of Doyogena sheep reported by CBBP members.

| Constraints |

R1 |

R2 |

R3 |

R4 |

R5 |

R6 |

R7 |

R8 |

Index |

Rank |

| Delay auditing | 38 | 30 | 22 | 13 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 0.1754 | 1 |

| Gap on keeping bylaw | 19 | 25 | 22 | 20 | 17 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 0.152 | 2 |

| Lack of trusts on CBBP leader | 16 | 17 | 19 | 24 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 4 | 0.1395 | 3 |

| Lack of market demand | 15 | 23 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 11 | 8 | 7 | 0.1389 | 4 |

| Aggressiveness of breeding ram | 13 | 13 | 12 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 13 | 20 | 0.1134 | 5 |

| Lack of credit access | 10 | 9 | 17 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 17 | 0.1061 | 6 |

| Concentrate feed shortage | 10 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 21 | 25 | 20 | 0.093 | 7 |

| Disease | 9 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 23 | 29 | 0.0817 |

8 |

participants and CBBP leaders to govern their breed improvement cooperative under the rule of the bylaws. However, the rules were not fully respected by the members of the CBBP. Some members do not follow to breeding ewe guidelines, cooperative leaders assigned by members are not trusted, and early selling of breeding rams and a shortage of concentrate feed are key bottlenecks in all Doyogena CBBP sites. The constraints mentioned by CBBP members across breeding cooperatives are nearly similar. The results were likely similar to those reported by Areb et al. (2021) for Bonga sheep and Gutu et al. (2015) for Bonga, Menz, and Horro CBBP.

Creating strong link among stakeholders for timely audits and extension support, improving communication channels between cooperative leaders and members to increase awareness of financial progress and decisions affecting the cooperative, provide training and support for cooperative leaders to ensure smooth transitions and effective leadership and arrange awareness creation meeting. By addressing these issues, Doyogena CBBP cooperatives can enhance their efficiency, transparency, and overall success in achieving their breeding objectives.

Conclusion

The CBBP participants working with group in the district generally confirmed the effectiveness, acceptability, and suitability of the breed improvement program. Sheep income contributed significantly to the improvement of the livelihood of farmers, especially for house building and providing food for their households. The CBBP participants had comparatively higher flock size, number of lambs born, and income from the sale of animals, and slaughter for home consumption compared to non-CBBP participants. The CBBP members perceived improvements in growth, coat color, litter size, lamb survival, and lambing interval. The number of selected rams, participant farmers, number of animals sold, and income have shown an increasing trend since the establishment of CBBP. However, the study identified several constraints in the Doyogena CBBP, including audit delays, gaps in bylaw compliance, a lack of trust in CBBP members and committees, and the aggressiveness of breeding rams. To ensure sustainable genetic improvement and effective utilization of resources, efforts should focus on improving stakeholder integration, advancing breeding cooperatives to a union level, and creating awareness among farmers. By involving more farmers in the CBBP and implementing genetic improvement programs, there is a great potential to increase farmers’ income in the Doyogena sheep CBBP and beyond.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Accelerating the Impact of CGIAR Climate Research in Africa (AICCRA) project and CGIAR initiative on “Sustainable Animal Productivity for Livelihoods, Nutrition and Gender inclusion (SAPLING)” for funding this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

novelty statement

We declare that this article is our orginal work and that we have duly acknowledged all sources of material used in this study.

Author contributions

Idea and research protocol: Addisu Jimma, Aynalem Haile, Aberra Melesse, and Tesfaye Getachew

Data collection, analyzing, writing the original draft and revising the final: Addisu Jimma

Checking statistical analysis, reviewing, and editing: All authors

Approved the final paper: All authors.

References

Abebe M. (1999). Husbandry practice and productivity of sheep in Lalo-mama Midir woreda of central Ethiopia. School of Graduate Studies of Alemaya University of Agriculture, Dire Dawa, Ethiopia. (M.Sc. thesis).

Addis G. (2015). Review on Challenges and Opportunities Sheep Production: Ethiopia African J. Basic Appl. Sci., 7(4): 200-205. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.ajbas.2015.7.4.9687.

Addisu J., Mestawet T., Aberra M., Deribe G., Asrat T., Aynalem H. (2021). Growth Performance Evaluation of Doyogena Sheep under Community based Breeding Scheme in Doyogena Woreda. Global J. Sci. Front. Res. Agricult. Vet. Volume 21 Issue 1 Version 1.0 Year 2021. Online ISSN: 2249-4626 & Print ISSN: 0975-5896.

Amare B., Yesihak Y., Wahid M. (2019). Breeding Practices, Flock Structure and Reproductive Performance of Begait Sheep in Ethiopia. J. Reprod. Infertilit. 10 (2): 24-39, 2019.

Areb E., Getachew T., Kirmani M., Haile A. (2021). Farmers’Perception on the Effect of Community-Based Sheep Breeding Program for Smallholder Production System-A Case of Bonga Sheep in Ethiopia. Int. J. Livest. Res., 11(11): 1-10. https://dx.doi.org/10.5455/ijlr.2021724080713 .

Asrat T., Tesfaye G., Aberra M., Mourad R., Barbara R.,Jouram M.M, Zelalem A., Aynalem H. (2021). Estimation of genetic parameters and trends for reproduction traits in Bonga sheep, Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod., https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02445

Ashenafi M., Addisu J., Shimelis M., Hassen H., Legese G. (2013). Analysis of sheep value chains in Doyogena, southern Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: ICARDA.

Ayele S., Assegid W., Belachew H., MA J., MM A. (2003). Livestock marketing in Ethiopia: A review of structure, performance and development initiatives. Socio-economics and Policy Research Working Paper 52. ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. pp.35

Aynalem H. (2021). Evaluation of the Progress of Community-Based Sheep Genetic Improvement Program in Horro Guduru Zone. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11766/66535

Beneberu T., Anteneh G., John A. (2011) Determinants of sheep prices in the highlandsof northeastern Ethiopia: implication for sheepvalue chain development. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. (2011) 43:1525–1533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-011-9837-x

Bhuiyan M.S.A., A.K.F.H. Bhuiyan, J.H. Lee, S.H. Lee (2017). Community based livestock breeding programs in Bangladesh: Present status and challenges. J. Anim. Breed. Genomics, 1: 77-84.

Budisatria I.G.S., H.M.J. Udo, C. Eilers, Z.A.J. VanDer (2007). Dynamics of small ruminant production: A case study of Central Java, Indonesia. Outlook on Agriculture, 36: 145-152.

CSA (2020). Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA): the 2020 Agricultural Sample survey, Report on Livestock and livestock characteristic. Volume II, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Dabesa Wegari Obosha (2020). Review on Gender Roles in Livestock Value Chain in Ethiopia. Ecol. Evolution. Biol. 5 (4): 140-147. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.eeb.20200504.14

Deribe G., A. Girma, T. Azage (2014). Influences of non-genetic factors on early growth of Adilo lambs under smallholder management systems. Trop. Anim. Health Prod., 46: 323-329.

Deribe .G, Girma Abebe, Azage Tegegne, B.S. Gemeda, Asrat Tera (2021). Factors Contributing to Sheep and Goat Flock Dynamics and Off Take Under Resource-Poor Smallholder Management Systems, Southern Ethiopia.

Dubale A., Yonnas A. (2021). Factors affecting the intensity of market participation of smallholder sheep producers in northern Ethiopia: Poisson regression approach. Anim. Husband. Vet. Sci. Res. Article. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2021.1874154

Esaya M., Jane W. (2019). Scaling Improved Sheep Fattening Practices and Technologies in Ethiopian Highlands. Sheep Fattening Business Case for Youth Groups.

Getachew T., Haile A., Tessema T., Dea D., Edea Z., Rischkowsky B. (2020). Participatory identification of breeding objective traits and selection criteria for indigenous goat of the pastoral communities in Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 52: 2145–2155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02243-4

Gutu Z., Haile A., Rischkowsky B., Annet A., Kinati W., Kassie G. T. (2015). Evaluation of communitybased sheep breeding programs in Ethiopia (Issue December). https://doi.org/hdl.handle.net/10568/76233 5.

Legesse G., G. Abebe, M. Siegmund-schultze, A. Vallezarate (2008). Small ruminant production in two mixed-farming systems of southern Ethiopia: status and prospects for improvement. Experimen. Agricult., 44: 399-412.

Luke M. (2010) Sheep Production Practices, Flock Dynamics, Body Condition and Weight Variation in Two Ecologically Different Resource Poor Communal Farming Systems. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Fort Hare, Alice. http://www.secheresse.info/spip.php?article44620.

Habte A., M. Ashenafi, T. Berhan, A. Getnet, F. Feyissa (2019). Feed Resources Availability and Feeding Practices of Smallholder Farmers in Selected Districts of West Shewa Zone, Ethiopia. World J. Agricult. Sci., 15(1): 21-30.

Haile A., Dessie T, Rischkowsky B.A. (2014). Performance of indigenous sheep breeds managed under community-based breeding programs in the highlands of Ethiopia: Preliminary results.

Haile A., Wurzinger M., Mueller J., Mirkena T., Duguma G., Rekik M., Mwacharo J., Mwai O., Sölkner J, Rischkowsky B. (2018). Guidelines for Setting Up community-based small ruminants breeding programs in Ethiopia. ICARDA—Tools and guidelines No.1. Beirut, Lebanon

Haile A, Gizaw S, Getachew T, Amer P, Rekik M B. R. (2019). Community based breeding programmes are a viable solution for Ethiopian small ruminant genetic improvement but require public and private investments. J. Anim. Breed. Genet., 136(5): 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbg.12401

Haile A., Getachew T., Mirkena T., Duguma G., Gizaw S., Wurzinger M., Soelkner J.

Mwai O, Dessie T., Abebe A., Abate Z., Jembere T., Rekik M., Lobo R. N. B.,

Mwacharo J. M., Terfa Z., G. Kassie, G. T., Mueller J. P., Rischkowsk, B. (2020). Community-based sheep breeding programs generated substantial genetic gains and socioeconomic benefits. Animal. (2020), 14:7, pp 1362–1370.

Haile A, Getachew T, Rekik M, Abebe A, Abate Z, Jimma A, Mwacharo JM, Mueller J, Belay B, Solomon D, Hyera E, Nguluma AS, Gondwe T, Rischkowsky B (2023), How to succeed in implementing community-based breeding programs: Lessons from the field in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Jane W. (2019). Scaling up Improved Sheep Fattening Practices and Technologies in Ethiopia. Implementation of Technologies for African Agricultural Transformation (TAAT) Livestock Compact. TAAT Technical Report August 2018 - January 2019.

Kassa Tarkegn (2021). What determine the price of Bonga sheep at the market level in Southwestern Ethiopia? A hedonic price analysis. Agricult. Food Security., December. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40066-021-00337-2.

Kaumbata W., H. Nakimbugwe, W. Nandolo, L.J. Banda, G. Mészáros. (2021). Experiences from the implementation of community-based goat breeding programs in Malawi and Uganda: A potential approach for conservation and improvement of indigenous small ruminants in smallholder farms. Sustainability, Vol. 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031494.

Kebede H., Aynalem H., Manzoor A.K, Tesfaye G. (2020). Estimates of Genetic Parameters and Genetic Trends for Growth Traits of Doyogena Sheep in Southern Ethiopia . Journal of Animal Breeding and Genomics. JABG. 2020 June, 4(2):33-49. https://doi.org/10.12972/jabng.20200004.

Kebede H., Tesfaye G., Aynalem H., Manzoor K., Addisu J. (2022). Reproductive and productive performance of Doyogena sheepmanaged under a community-based breeding program in Ethiopia. Livest. Res. Rural Develop.

Kebede, H., T. Getachew, A. Haile, A. Kirmani, A. Jimma, D. Gemiyo, (2022). Farmers perceptions to community-based breeding programs: A case study for Doyogena sheep in Ethiopia. Asian J. Anim. Sci., 16: 45-54.

Kocho T., G. Abebe, A. Tegegne, B. Gebremedhin (2011). Marketing value-chain of smallholder sheep and goats in crop-livestock mixed farming system of Alaba, Southern Ethiopia. Small Rumin. Res., 96: 101-105.

Kosgey I.S. (2004). Breeding objectives and breeding strategies for small ruminants in the Tropics. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands. (ISBW: 90-5808-990-8) Germany.271p.

Kosgey I S, Baker R L, Udo H M J , Van Arendonk J A (2006). Successes and failures of small ruminant breeding programmes in the tropics: a review. Small Rumin. Res., 61(1): 13-28.

Mapiliyao L., D. Pepe, U. Marume, V. Muchinje (2012). Flock dynamics, body condition and weight variation in sheep in two ecologically different resource-poor communal farming systems. Small Rumin. Res., 104: 45-54.

Mirkena T. (2010). Identifying Breeding Objectives of Smallholders ⁄ Pastoralists and Optimizing Community-Based Breeding Programs for Adapted Sheep Breeds in Ethiopia. University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), Vienna.

Mirkena T., G. Duguma, A. Willam, M. Wurzinger, A. Haile (2012). Community-based alternative breeding plans for indigenous sheep breeds in four agro-ecological zones of Ethiopia. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 129: 244-253.

Mueller J.P, Rischkowsky B., Haile A., Philipsson J., Mwai O, Besbes B, Valle Zarate A., Tibbo M., Mirkena T., Duguma, G., Sölkner J., Wurzinger M. (2015). Community-based livestock breeding programmes: Essentials and examples. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 132: 155–168.

Rekik M., Haile A., Abebe A., Muluneh D., Goshme S., Ben Salem I. (2016). GnRH and prostaglandin-based synchronization protocols as alternatives to progestogen-based treatments in sheep. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 51: 924–929. https://doi.org/10. 1111/rda.12761.

SAS (2012). Statistical Analysis System. SAS for Windows, Release 9.3. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA

Solomon G., Hans Komen, Johan A.M. van Arendonk (2010). Participatory definition of breeding objectives and selection indexes for sheep breeding in traditional systems. Livest. Sci., 128: 67-74.

Shenkute B., Getahun L., Azage T., Hassen A. (2010) Small Ruminant Production in Coffee-Based Mixed Crop-Livestock System of Western Ethiopian Highlands: Status and Prospectus for Improv. Livest. Res. Rural Develop.

Shigdaf M., Zeleke M., Mengisite T., Asresu Y., Habitemariam A., Aynalem, H. (2012). Traditional management system and farmers’ perception on local sheep breeds (Washira and Farta) and their crosses in Amhara region, Ethiopia.

Tassew M, Kefelegn K., Yoseph M., Bosenu A. (2014).Herd Management and Breeding Practices of Sheep Owners in North Wollo Zone, Northern Ethiopia. Middle-East J. Scient. Res. 21 (9). https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2014.21.09.21730.

Taye M. Yilma M., Rischkowsky, B. Dessie T., Okeyo M., Mekuriaw G, Haile A. (2016). Morphological characteristics and linear body measurements of Doyogena sheep in Doyogena district of SNNPR, Ethiopia.

Terfa Z. G. (2012). Sheep Market Participation of Rural Households in Western Ethiopia. African J. Agricult. Res., 7(10): 1504–1511. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajar11.747.

Tibbo M. (2006). Productivity and health of indigenous sheep breeds and crossbreds in the central Ethiopian highlands. Ph D. Thesis. Swedish Univ. Uppsala, Sweden.

Verbeek M. (2004). A Guide to Modern Econometrics (Second Edition ed.). John Wiley and Sons Ltd, TheAtrium, Southern Gate, Chichester.

Weldemariam B., G. Mezgebe (2020). Community based small ruminant breeding programs in Ethiopia: Progress and challenges. Small Rumin. Res., Vol. 196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. smallrumres.2020.106264.

Wurzinger M, Solkner J, Iñiguez L (2011) important aspects and limitations in considering community-based breeding programs for low-input smallholder livestock systems. Small Rumin. Res. 98:170-175.

Wurzinger, M., G.A. Gutiérrez, J. Sölkner, L. Probst, (2021). Community-based livestock breeding: Coordinated action or relational process? Front. Vet. Sci., Vol. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets. 2021.613505

Yamane T. (1967). Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd edition, NewYork:

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?