Does Women’s Participation in Livestock Management Enhance their Empowerment? An Insight from the Tribal Belt of Pakistan

Shaista Naz1*, Noor P. Khan1, Himayatullah Khan1 and Azra2

1Institute of Development Studies (IDS), The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; 2Department of Economics, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | Women served as the major participant in livestock management at the domestic level and supporting rural livelihoods with the provision of multiple products for consumption and sale. However, the question arises that women’s participation in livestock management has some relation to their empowerment or it is not a debatable issue. To address the issue, this research is carried out in the tribal areas of Pakistan for which data were collected from 323 randomly selected female respondents from 323 randomly selected households in Mohmand Agency. The collected data were analyzed using percent participation, descriptive statistics, and Decision Making Index (DMI). The results showed that the decisions related to livestock management were mostly taken by both women and men jointly (44%), followed by men alone (27 %) and women (25%) independently. It has been found that six kinds of livestock management activities such as milk/by-products and its marketing, milk handling and processing, animal health problems, animals keeping place, and number and breed of animals were more significant for assessing women empowerment as depicted by the high DMI value of above 0.80. Moderate level of women empowerment was observed in the activities of animals’ purchase (0.57), animals’ sale (0.59), and livestock income utilization (0.63) due to their low level of mobility and technical know-how. Almost all the household activities were directly related to the power of men due to the DMI value of below 0.50. The average DMI was 0.98 for livestock management activities as compared to 0.42 for household matters which indicate that women were enjoying a high level of decision-making power/empowerment in livestock management as compared to household matters. The study concludes that women’s participation enhances women’s empowerment. However, the provision of technical knowledge and guidance to women are suggested to increase their participation in the decisions related to livestock management activities and ultimately for women empowerment. Moreover, there is still a need to enhance women’s decision-making power at the household level for the development of Pakistani society.

Received | January 04, 2018; Accepted | July 03, 2020; Published | August 07, 2020

*Correspondence | Shaista Naz, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; Email: [email protected]

Citation | Naz, S., Khan, N.P., Khan, H. and Azra. 2020. Does women’s participation in livestock management enhance their empowerment? An insight from the tribal belt of Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 36(3): 823-831.

DOI | http://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.3.823.831

Keywords | Rural women, FATA, Women empowerment, Livestock management and Household matters

Introduction

Social scientists have contended that the balance of power within the household is inclined by the resources that each bring to the partnership. The power rests with those who had more resources (Mahadi et al., 2015). If a woman contributes more to the household income, her power should be improved which is considered as the decision-making authority within the household. In tradtional societies, like Pakistan, men generally enjoy the decision-making authority due to patriarchy (Anwar et al., 2013). The situation prevails more in the ruarl areas where women’s literacy and educational levels were found low due to the various religious, socio-cultural, and economic constraints (Iqbal et al., 2013). In the recent era of development, the literacy and educational levels of women showed progress.

The overall female literacy rate of women in the country stands for 58% as compared to 60 % in the previous year (2015). The litaercy rate for urban women stands much hihgher than rural women. Thus, women in urban areas due to high literacy status and educational rates changing their lives day by day by attaining employment in the various government and non-government sectors (GoP, 2016-17). Acquiring a paid job, these women in urban areas are enjoynig high level of decsion-making power not only over their own lives but also influencing other household decisions (Ali et al., 2015). By attaing high level of decsion-making power they are called empowered women. The situation is reverse for rural women (Iqbal et al., 2013).

Women, in the rural areas do not only have low levels of literacy and education but also their mobility is restricted. These women are more bound in culture, religion and patriarchy which controlled their lives (Adeel et al., 2013). Despite, all these boundness and unfavourable situation for progress, rural women still have a lot to do. They work not only inside their home premises but also work outside (Naz and Khan, 2018). They work for longer hours than men in the various fields of agriculture (Ahmad, 2014; Zahoor et al., 2013; Khan et al., 2012). However, they are mostly the unpaid labour force of agriculture (FAO, 2015).

Just like other agricultural activities, women in rural areas are predominantly involved in livestock production and management. They work for longer hours as compared to their male counterparts in the livestock sector (Naz and Khan, 2018; Andaleeb et al., 2017; Ahmad, 2014; Zahoor et al., 2013). Without the help of women, the livestock activities cannot be completed (FAO, 2015). In fact, women support their male counterparts in every sphere of work especially in livestock management and thus contribute to household’s income and livelihoods (Ahmad, 2014; UNICEF, 2008). Their obvious role in livestock management can be shown from the fact that a total of more than 8 hours/day is required for all the livestock management activities (Amin et al., 2010) of which major time share comes from women’s side (Andaleeb et al., 2017). Animal raising mode and ecosystem are responsible for the varying role of women in livestock production and management (Jamali, 2009).

The literature confirmed that women are highly participating in livestock management (Naz et al., 2018; Andaleeb et al., 2017; Ahmad, 2014; Batool, 2014; Zahoor et al., 2013; Amin et al., 2010). However, women’s improved status and empowerment is significantly related to their participation in the decision-making process (Mahadi et al., 2014; Begum, 2002) but generally, women had low level of participation in the livestock related decisions (Riasat et al., 2014). Their low level of involvement in the decision-making process resulted in the exclusion of their specific interventions in the policies and laws and thus lowering their levels of empowerment. The contribution of rural women in livestock management is very important and fundamental. However, a question arises in mind that is women have low levels of decision making power in livestock management in the tribal belt too? This question further requires information that if it is not the case then does women’s participation in livestock management enhance their empowerment? Especially, in the most underdeveloped areas of the country such as Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) where women were more bound to cultural and patriarchal norms.

The tribal belt of Pakistan, is one of the neglected parts of the country not only politically but also at developmental aspects. The militancy and Talibanization also severely affected the economic conditions of the area. The male population of the area leave their homes due to the bad economic conditions and left behind their women. These women not only perform the inside home duties but also work outside like agricultural activities. Due to the cultural constraints, women of the area have no interaction with the outside world like other parts of the country. They spend their whole lives within the boundaries of their respective areas. These women are illiterate and have no prospects of paid work. Agricultural activities like livestock management in which these women are involved is totally unpaid work (FAO, 2015). The common perception about these women is that they are the most oppressed, deprived, and differentiated group with low or even no empowerment. To identify the true picture of their level of empowerment in livestock management the present study is conducted. Although the work performed by these women in livestock management is unpaid, but by managing it they support their families in terms of food, fuel and income etc. (Naz and Khan, 2018). Thus, their support can increase their decision-making power or empowerment. Moreover, women’s level of empowerment is also measured in the selected household matters to compare it with the livestock management.

Keeping in view the above discussion, it is known that women highly participated in livestock management in the tribal belt of the country (Naz and Khan, 2018; FAO, 2015). However, women’s role in livestock related decisions has not been properly explored yet. Keeping in view all this, the present research study is designed to answer these research questions: 1) To what extent the women are empowered in livestock management; 2) In which aspects of livestock management they are empowered; and 3) Are women more empowered in livestock management as compared to household other matters? These questions further answered the main research question of this research study “does women’s participation in livestock management enhance their empowerment in the tribal belt of the country?”.

Materials and Methods

Study area description

The study was conducted in the rural areas of FATA, Pakistan. It was selected as the study area because it is one of the underdeveloped areas of the country and having 64 % of its population living below the poverty line (Markey and Daniel, 2008). Due to high prevalence of poverty male population mostly seek overseas employment. Women of the area left at home and had splendid work to do not only inside the home premises but outside too. The household activities of the women included care of children, cooking, washing, cleaning homes etc. and the most important one of livestock rearing. They perform various livestock activities like feeding, watering, shed cleaning, bathing, milking and milk products preparation. The outside activities were mostly of agricultural like vegetable production and watering animals (FAO, 2015). All the work is unpaid. The cultural factors restrained women not only from education attainment but also from getting a paid job. The literacy rate of women is only 12.5 % which is very low (Planning and Development Department FATA, 2014) and thus women had to play the traditional roles inside and outside their homes as mentioned earlier. It is believed that women of the area are the most deprived, differentiated and disregarded group of Pakistani society. However, women’s role in agriculture and mostly in livestock management provided them with opportunities to prosper and get a chance of say in the important decisions. Women’s empowerment/decision making power was not previously measured by the researchers. Thus, measuring women’s empowerment level in livestock management is desirable. FATA consists of seven Agencies (Mohmand, Khyber, Kurram, Bajaur, Orakzai, North Waziristan and South Waziristan) and six Frontier Regions (FRs) which are FR Peshawar, FR Kohat, FR Bannu, FR Lakki Marwat, FR Tank and FR Dera Ismail Khan. The current study is conducted in a randomly selected Mohmand Agency. The Agency shares a border with the Bajaur Agency to the north, the Dir district to its east, the district of Peshawar to its south-east and Afghanistan to the west. The agency had two administrative units i.e. Lower Mohmand and Upper Mohmand. Lower Mohmand consists of four Tehsils namely Yakka Ghund, Pindiali, Utman Khel, and Pranghar while, Upper Mohmand comprises of three Tehsils i.e.; Safi, Halimzai, and Upper Mohmand (Figure 1).

Sampling and data collection

The primary data were collected during the period of February and May 2016. Through multistage sampling technique, a sample size of 323 households was selected. In the first stage of the sampling, Mohmand Agency was selected as mentioned earlier. In the second stage, two tehsils i.e. Halimzai and Pindiali were selected randomly. In the third stage, three sub-tribes were selected randomly from each tehsil. In the fourth and final stage, households from the selected sub-tribes were selected randomly using the list of households provided by the Planning and Development Department of FATA and Livestock and Dairy Department of Mohmand Agency. The sample size was proportionally distributed among the sampled sub-tribes as seen in Table 1.

Table 1: Distribution of sampled households in the selected sub-tribes.

|

Selected tehsil |

Selected sub-tribe |

Livestock rearing households |

Sampled households |

|

Halimzai |

Kachi Khel |

1189 |

48 |

|

Hamza Khel |

448 |

18 |

|

|

Kuz Kadi Khel |

2654 |

106 |

|

|

Pindiali |

Isa Khel |

2100 |

84 |

|

Bar Burhan Khel |

1000 |

40 |

|

|

Kuz Burhan Khel |

666 |

27 |

|

|

Total sampled households |

323 |

||

Data collection was done from women respondents through a pretested structured questionnaire. Women were selected as the respondents of the study due to their high participation in livestock management. The women were face to face interviewed in the context of shared research principles and research ethics (Khan et al., 2017). The interviews were conducted from the willing respondents by explaining the purpose and objectives of the study and usage of data for the research purpose. The respondents who refused to provide any answer at the briefing stage were replaced with the other households.

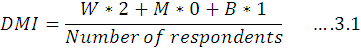

Analytical techniques

Decision Making Index (DMI) was used to measure women empowerment in the livestock management and household matters. Empowerment of rural women is indicated by the significant change in DMI which reveals more power on various aspects of women. For the determination of DMI, a three points scale (i.e.; decision taken by women alone was assigned 2, men and women together 1 and men alone was assigned 0) was employed (Mahadi et al., 2014). The formula of DMI is given in Equation 3.1 as follow;

Where;

DMI is, the decision-making index, W denotes decision is taken by women alone, M shows that decision was taken by men alone and B indicates that decision was taken by both men and women jointly. The DMI value ranges between 0-1. The DMI value with “0” depicts that women have no empowerment while, the DMI value “1” indicates perfect empowerment of women. Looking in to the traditional nature of the society, for the easiness, this study divided the DMI values in to values of “0.80” which showed high level of women empowerment, “0.60” indicated medium or moderate level of women empowerment. For the no empowerment or low level of women empowerment the value of “0.40” was assigned. The average DMI value for all the decisions in the categories of livestock management activities and household matters was used for comparison.

Moreover, percent participation of women in the decisions related to livestock management and household matters were also estimated.

Description of decision-making areas

Here, women empowerment was measured in the two categories i.e. livestock management and household matters to get a clearer picture of the situation. The detail of the decision-making areas regarding livestock management and household matters is given as follow:

Livestock management decisions: The decisions regarding livestock management activities included purchase of animals, sale of animals, number and breed of animals, animals’ keeping place, breeding, animals’ treatment, milk processing and handling, marketing of milk and milk products, and livestock income utilization (Table 2).

Household matters decisions: Food expenditures, children education, family planning, marriage, house repairing, household assets purchase, and other business activities were the main decision-making areas of household matters (Table 3).

A three-point scale was used to record women participation in decision-making regarding livestock management and household matters. Decisions were recorded as; taken by women (independent decision), men (independent decision) and both by women and men (Joint decision).

Limitations of the study

The research study focused on one Agency of the tribal areas, thus results cannot be representative of the whole FATA. However, the results can be generalized for the geographical areas having same socio-economic conditions like the study area. Almost all the respondents were illiterate, so there is a chances of memory lapses of the respondents during data collection. Moreover, the skeptical respondents were made sure about the secrecy of information and the usage of data for the research purpose only.

Results and Discussion

Percent participation of women in the livestock management decisions

Data in Table 2 show that the overall decision-making process in all livestock management activities was 44% of both men and women, followed by 29% of men and 27% for women. In the case of livestock activities, data in Table 2 denote that both men and women’s participation in decision-making process were found high for number and breed of animals (59%) followed by animals’ keeping place (56%). The results are supported by Upadhyay and Desai (2011) who found that rural women jointly made decisions with their husbands regarding the selection of animals in district Anand of Gujarat, India. In the case of feeding practices and livestock income utilization 52% and 50% respondents were made joint decisions with their household heads. On the other hand, men’ participation in the decision-making process was found to the medium level for animals’ purchase (52%) and animals’ sale (50%). The activities of animals’ purchase and animals ‘sale are outdoor activities which require traveling outside the home and technical know-how. Due to this, female participation was found low in these activities. Moreover, these activities are time-consuming and rural women have other domestic and livestock related responsibilities inside their homes. Therefore, the decisions are mainly taken by male independently. The results are like Arshad et al. (2010) who reported that rural women had relatively low participation in animals’ sale in Pakistan. Similarly, Katiyar et al. (2008) noted that female had a low level of participation in the decisions related to the animal purchase and sale in India.

The participation of rural women in decision making process was higher for milk handling and processing (61%) and marketing of milk and by products (67%). The results imply that rural women were not only involved in livestock management but also, they have to take care of the dietary supplies, needs, and preferences of other household members. This influence and become the apparent reason of women’s participation in decision-making process of the activities; quantity of milk to be used for home consumption and type of milk product to be made. Mulugeta and Amsalu (2014) reported that rural women were mostly involved in the final decisions of milk and milk products’ sale in Ethopia. These findings are also supported by Sarma and Payeng (2012) and Singh and Srivastava (2012) who also reported that in India that women are prime actors in milk handling and processing at household level. The results imply that both men and rural women decided for most of the livestock activities jointly; however, the men were found dominant in the important decisions like animals’ purchase and sale, while women are enjoying higher participation in the decisions of milk handling and processing and marketing of milk and by-products in the study area.

Table 2: Percent participation of men, women, and both in decision-making regarding livestock activities.

|

Livestock management decisions |

Men (%) |

Women (%) |

Both (%) |

|

Animal’s purchase |

52 |

8 |

40 |

|

Animal’s sale |

50 |

9 |

41 |

|

Number and breed of animals |

22 |

19 |

95 |

|

Animals keeping place |

20 |

24 |

56 |

|

Feeding practices |

36 |

12 |

52 |

|

Milk handling and processing |

5 |

61 |

34 |

|

Milk and by products marketing |

3 |

67 |

30 |

|

Animal health problems and treatment |

29 |

35 |

36 |

|

Livestock income utilization |

44 |

6 |

50 |

|

All decisions |

29 |

27 |

44 |

Percent participation of women in household matters’ decisions

Women’s participation in the decision-making process regarding household matters served as an important indicator of women’s empowerment (Adeel et al., 2013). Household welfare can be achieved by the distribution of the equal share of participation between the couples. The data in figure Table 3 revealed that overall participation in decision making was 6%, 62%, and 32% of rural women, men and both regarding household activities. It shows that men were the major decision makers in the study area for household matters. The results are in line with Hoque and Itohara (2008) who stated that women are less involved in family decisions than men in Bangladesh. The data in Table 3 further show that men were dominant in all the decisions related to food expenditure, children education, family planning, marriage, house repairing, household assets purchase and business purpose activities with the respective percent participation of 64, 61, 59, 53, 66, 66 and 65. The findings are in line with Nosheen et al. (2009) who noted that in the case of household activities the decisions were mainly taken by a male in Punjab Province of Pakistan.

Table 3: Percent participation of men, women, and both in decision-making regarding household activities.

|

Household matters’ decisions |

Men (%) |

Women (%) |

Both (%) |

|

Food expenditures |

64 |

6 |

30 |

|

Children education |

61 |

6 |

33 |

|

Family planning |

59 |

7 |

34 |

|

Marriage |

53 |

7 |

40 |

|

House repairing |

66 |

5 |

29 |

|

Household assets purchase |

66 |

5 |

29 |

|

Business |

65 |

5 |

30 |

|

All decisions |

62 |

6 |

32 |

Women empowerment

Women’s decision making power is an important indicator for assessing women empowerment. The better empowerment status of women can be shown by the significant change in DMI which further revealed more power on different household aspects of women (Mahadi et al., 2014). In the present study, DMI and women empowerment was positively related with each other. It is evident from the data in Table 4, that six kinds of activities regarding livestock management such as milk/by-products and its marketing, milk handling and processing, animal health problems, animals keeping place, and number and breed of animals were more significant for assessing women empowerment due to the high DMI value of above 0.80. Among these, three decisions of milk/by-products and its marketing, milk handling and processing, animal health problems showed higher DMI values of above 1 which are due to the women’s independent decisions. Furthermore, the DMI values for the livestock activities of animals’ purchase (0.57), animals’ sale (0.59), and livestock income utilization (0.63) indicate for a moderate level of women empowerment due to the DMI value of below 0.60. The results show that for these important activities, women decision making power needs consideration. On the other hand, food expenditure, education of children, house repairing, purchasing household assets, and business activities were directly related to the power of men due to the DMI value of below 0.50. Only two decisions of family planning and marriage showed the DMI value above 0.50 which indicates the moderate level of women empowerment. The data in Table 4 further shows that the average DMI values stands 0.98 for livestock management activities as compared to 0.42 for household matters. These findings are similar to the findings of Mahadi et al. (2014) who found a higher DMI value (1.03) for livestock and poultry rearing as compared to household matters (0.98) in Bangladesh. The results of the present study indicate that women were enjoying a high level of empowerment in livestock management due to their financial and other contribution to household by managing livestock. However, in household matters women had low level of empowerment. It further implies that by increasing women’s financial contribution their decision-making power may be enhanced and thus their level of empowerment.

Table 4: Comparison of DMI between livestock and household matters in the study area.

|

Variables |

Men (No) |

Women (No) |

Both (No) |

DMI |

|

|

Livestock Activities |

|||||

|

Animal purchase |

166 |

27 |

130 |

0.57 |

|

|

Animal sale |

162 |

29 |

132 |

0.59 |

|

|

Number and breed of animals |

71 |

62 |

190 |

0.97 |

|

|

Animal keeping place |

66 |

77 |

180 |

1.03 |

|

|

Feeding practices |

116 |

39 |

168 |

0.76 |

|

|

Milk handling and processing |

15 |

199 |

109 |

1.57 |

|

|

Milk/by-products’ marketing |

10 |

219 |

98 |

1.63 |

|

|

Animal health problems |

95 |

141 |

114 |

1.06 |

|

|

Livestock income utilization |

141 |

20 |

162 |

0.63 |

|

|

Average DMI |

0.98 |

||||

|

Household activities |

|||||

|

Food expenditures |

226 |

19 |

78 |

0.36 |

|

|

Children education |

209 |

19 |

95 |

0.41 |

|

|

Family planning |

182 |

27 |

114 |

0.52 |

|

|

Marriage |

159 |

24 |

140 |

0.58 |

|

|

House repairing |

222 |

19 |

82 |

0.37 |

|

|

Household assets purchase |

234 |

18 |

71 |

0.33 |

|

|

Business |

226 |

18 |

79 |

0.36 |

|

|

Average DMI |

0.42 |

||||

Conclusions and Recommendations

It is concluded that both men and women took joint decisions of livestock management while, the decisions related to household matters were dominated by male. The results of DMI show that women had higher level of empowerment in livestock management while, in household matters they had low level of empowerment. Six activities of livestock management such as milk/by-products and its marketing, milk handling and processing, animal health problems, animals keeping place, and number and breed of animals were more significant for assessing women empowerment due to the high DMI value. Among these, three decisions of milk/by-products and its marketing, milk handling and processing, animal health problems showed for higher DMI values of above the threshold which are due to the women’s independent decisions. Only in the livestock management activities of animal’s purchase, animal’s sale and livestock income utilization women showed moderate level of empowerment due to their limited mobility and low level of technical know-how.

The study concluded that women’s participation in livestock management enhances women empowerment as they played a significant role in the decision-making concerning the livestock management as compared to the household matters. The provision of technical knowledge and guidance to women are suggested to increase their participation in the decisions related to livestock management activities and ultimately for higher levels of women empowerment. Furthermore, there is still a need to enhance women’s level of empowerment at household level for the development of tribal as well as Pakistani society.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely thankful to the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), The University of Agriculture, Peshawar, Pakistan, Planning and Development Department of Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan, and local households’ women representatives for their effective support and coordination in organizing and conducting successful household interviews and completion of this research study.

Novelty Statement

This research highlighted provision of technical knowledge and guidance to women of Tribal Areas of KP-Pakistan in order to increase their participation in livestock activities. It would ultimately enhance women empowerment at household level.

Author’s Contribution

Shaista Naz conceived the idea of research which has been refined by Noor P. Khan. Shaista Naz also did data collection, its entry and analysis. The writing and overall management of the article were also done by the first author. Noor P. Khan also provided the technical support. Himayatullah Khan had done reviewing and technical guidance. Azra helped in writing and data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Adeel, M. and Y.G.O. Anthony and F. Zhang. 2013. Gender, mobility and travel behavior in Pakistan: Analysis of 2007 Time Use Survey. MPRA, Paper No. 55474.

Ahmad, T.I., 2014. The role of rural women in livestock management: Socio-economic evidences from diverse geographical locations of Punjab (Pakistan). Geography. Universit´e Toulouse le Mirail - Toulouse II, 2013.

Ali, H., R. Bajwa and U. Hussain. 2015. Women’s empowerment and human development in Pakistan: An elaborative study. Asian J. Manage. Sci. Educ., 4(4): 23-30.

Amin, H., T. Ali, M. Ahmad and I.Z. Muhammad. 2010. Gender and development: Roles of rural women in livestock production in Pakistan. Pakistan J. Agric. Sci., 47: 32-36.

Andaleeb, N., M. Khan and S.A. Shah. 2017. Factors affecting women participation in livestock farming in District Mardan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 33(2): 288-292. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2017/33.2.288.292

Anwar, B., M. Shoaib and S. Javed. 2013. Women’s autonomy and their role in decision making at household level: A case of rural Sialkot, Pakistan. World. Appl. Sci. J., 23(1): 129-136.

Arshad, S., S. Muhammad, A. Mahmood, I.A. Randhawa and M.C.H. Khalid. 2010. Rural women’s involvement in decision-making regarding livestock management. Pak. J. Agric. Sci., 47(2): 1-4.

Arshaq, S.M., A. Ashfaq, M. Saghir, M.A. Ashraf, H. Lodhi, Tabassum and A. Ali. 2010. Gender and decision-making process in livestock management. Sarhad J. Agric. 26(4): 693-696.

Batool. Z., H.M. Warriach, M. Ishaq, S. Latif, M.A. Rashid, A. Bhatti, N. Murtaza, A. Arif and P.C. Wynn. 2014. Participation of women in dairy farm practices under smallholder production system in Punjab, Pakistan. J. Anim. Plant Sci., 24(4): 1263-1265.

Begum, A., 2002. Views on women’s subordination and autonomy: Blumerg re-visited, Empowerment. 9: 85-96.

Biradar. N., M. Desai, L. Manjunath and M.T. Doddamani. 2013. Assessing contribution of livestock to the livelihood of farmers of western Maharashtra. J. Hum. Ecol. 41(2): 107-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2013.11906557

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2015. Women in agriculture in Pakistan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Islamabad, 2015.

FAO, 2011. The state of food and agriculture 2010-11. Women in agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development. FAO, Rome, Italy.

GoP (Government of Pakistan). 2015-16. Economic Survey of Pakistan. Ministry of finance. Islamabad.

GoP (Government of Pakistan). 2016-17. Economic survey of Pakistan. Finance division, Islamabad.

Hoque, M. and Itohara, Y. 2008. Participation and decision making role of rural women in economic activities: A comparative study for members and non-members of the micro-credit organizations in Bangladesh. J. Soc. Sci., 4(3): 229-236.

Iqbal, S., A. Mohyuddin, Q. Ali and M. Saeed. 2013. Female education and traditional attitude of parents in rural areas of Hafiz Abad Pakistan. Middle-East J. Sci. Res., 18(1): 59-63.

Jamali, K., 2009. The role of rural women in agriculture and its allied fields: A case study of Pakistan. Eur. J. Soc. Sci., 7: 74-75.

Katiyar, S., G.P. Acharya and S.N. Tripathi. 2008. Role of farm women in decision making concerning farm and home activities. Rajasthan J. Ext. Educ., 16: 195-198.

Khan, W., N. Khan and S. Naz. 2017. Beekeeping in Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan; Opportunities and Constraints. Sarhad. J. Agric., 33(3): 459-465. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2017/33.3.459.465

Khan, M., M. Sajid, B. Hameed, N.M. Khan and A.U. Jan. 2012. Participation of women in agriculture activities in district Peshawar. Sarhad J. Agric., 28(1): 121-127.

Mahadi, M.S.A., R. Khanum and K. Akhi. 2015. Participation in livestock and poultry rearing: A study on haor women in Bangladesh. J. Chem. Biol. Phys. Sci., 4 (4): 3850-3860.

Markey and S. Daniel. 2008. Securing Pakistan’s tribal belt. Council on foreign relations. p. 5. ISBN 0-87609-414-0.

Mulugeta, M. and T. Amsalu. 2014. Women’s role and their decision making in livestock and household management. J. Agric. Ext. Rural. Dev., 6(11): 347-353.

Naz, S. and N.P. Khan. 2018. Financial contribution of livestock at household level in Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan: An empirical perspective. Sarhad. J. Agric., 34(1): 1-9. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2018/34.1.1.9

Naz, S., N.P. Khan, N. Afsar and A.A. Shah. 2018. Women’s participation and constraints in livestock management: A case of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 34(4): 917-923. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2018/34.4.917.923

Nosheen, F., T. Ali, M. Ahmad and H. Nawaz. 2009. Exploring the gender involvement in agricultural decision making: A case study of district Chakwal, Pakistan. J. Agric. Sci., 45(3): 101-106.

Pal, S., 2013. Participation of rural women in agriculture and livestock in Burdwan district, West Bengal, India: A regional analysis. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Interdisciplin. Res. 2(4): 66-80.

Riasat, A., M.I. Zafar, I.M. Khan, R.M. Amir and G. Riasat. 2014. Rural development through women participation in livestock care and management in district Faisalabad. J. Glob. Innovative Agric. Soc. Sci. 2(1): 31-34. https://doi.org/10.17957/JGIASS/2.1.458

Sarma, J. and S. Payeng. 2012. Women dairy farmers and decision making pattern in Sonitpur District of Assam. Indian J. Hill. Farming. 25(1): 58-62.

Singh, B. and S. Srivastava. 2012. Decision making profile of Ummednagar village of Jodhpur district. Indian Res. J. Ext. Educ., Special Issue, 1: 235-137.

Upadhyay, S. and C.P. Desai, 2011. Participation of farm women in animal husbandry in Anand district of Gujarat. J. Com. Mobiliz. Sustain. Dev., 6(2): 117-121.

UNICEF. 2008. An Analysis of the Situation of Women and Children in Balochistan. United Nation International Children Education Fund. UNICEF Pak. Ann. Rep. pp. 6-36.

Zahoor, A., A. Fakher, S. Ali and F. Sarwar. 2013. Participation of rural women in crop and livestock activities: a case study of tehsil Tounsa Sharif of southern Punjab (Pakistan). Int. J. Adv. Res. Manage. Soc. Sci., 2(12): 98-121.

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?