Reducing Poverty Through Irrigation Investment: A study of Palai Dam Irrigation Canal, District Charsadda

Research Article

Reducing Poverty Through Irrigation Investment: A study of Palai Dam Irrigation Canal, District Charsadda

Muhammad Jamal Nasir*, Anwar Saeed Khan, Atiq Ur Rahman, Waqar Akhtar and Hafizullah Khan

Department of Geography and Geomatics, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | Construction of the dam brings far-reaching changes in the economy and lifestyle of the dam command area. Palai dam is constructed some 16 km from Tangi town and 40 km north of Charsadda city on river Jindai in 2011. The main purpose of the dam is to irrigate 4600 acres of agricultural land in four villages of district Charsadda. This paper is aimed to study the socio-economic impact of Palai Dam on village Qilla and Palai Nasratzai located in tehsil Tangi, district Charsadda, falling in the command area of the dam. The study is based on both primary and secondary data. The primary data regarding household characteristics and socio-economic conditions was collected through a structured and pre-tested questionnaire and focus group discussions. Whereas the secondary data was acquired from the revenue office Tehsil Tangi. According to field survey and analysis of primary data, in Palai Nasrat Zai, the total revenue generated per household from both Kharif and Rabbi crops was PRs. 488511.68 in 2008-09 which increased to Rs.1089252.42 after the dam construction in 2016-17. In Village Qilla the net per household revenue from both Rabi and Kharif crops in 2008-09 was PRs. 33796.05 which increased to PRs. 66541.74 in 2016-17 after the dam construction. The net income is almost doubled after the dam construction. Thus, this increase in net income is reflected in the socio-economic condition of both villages. Moreover, the area showed the growth of private schools. Also, people are availing the private medical facilities. Furthermore, the proportion of Pacca houses also increased after the dam construction.

Received | November 29, 2023; Accepted | May 24, 2024; Published | July 16, 2024

*Correspondence | Muhammad Jamal Nasir, Department of Geography and Geomatics, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.; Email: [email protected], [email protected]

Citation | Nasir, M.J., A.S. Khan, A.U. Rahman, W. Akhtar and H.U. Khan. 2024. Reducing poverty through irrigation investment: A study of Palai dam irrigation canal, district Charsadda. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 40(3): 799-809.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2024/40.3.799.809

Keywords | Socio-economic impact, Revenue record, Palai Dam, Rabi cropping, Kharif Cropping, Socio-economic development

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Water is significant for the 850 million global poor’s mainly for those practicing agriculture. Irrigation water is the main constraining factor in desirable agricultural output and income in many low and middle-income countries (LMIC). Agriculture and livestock production, fishing, recreations, industrial processing, and human well beings are all influence by the quantity and quality of water (Namara et al., 2010). Irrigation’s socioeconomic influence is extremely complicated and diversified (Saleth et al., 2003). In this regard, several factors are responsible including land holding, crop type, cropping intensity, land and labor productivity, etc. In some cases, irrigation increases the utilization of agricultural inputs i.e. fertilizers and high-yielding varieties which can improve agricultural production and in turn contributes to poverty alleviation. Besides, the impact of irrigation is especially pertinent for areas with highly variable rainfall both in time and space (Gebregziabher et al., 2009).

The literature on irrigation and its influence on agricultural productivity and farmer socioeconomic situations are diverse and contradictory. Government irrigation expenditures, according to Fan et al. (2000), have a minimal influence on agricultural performance. Similarly, Songging et al. (2002) find no link between irrigation development and agriculture production. Higginbottom et al. (2021) evaluate the performance of 79 irrigation schemes from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and find out that investment in irrigation schemes failed to deliver the desired results. Pender et al. (2004) also reported the same findings. It is feasible, however, to enhance agricultural yield and productivity by providing a reliable as well as a year-round source of irrigation water. Many studies have conveyed the positive influence of irrigation on agricultural output and, as a result, the lives of diverse farmer communities in Africa (Awulachew and Merrey, 2007; Kassam et al., 2011; Amede, 2015; Garbero and Songsemasawas, 2018; Balana et al., 2020).

Numerous studies indicate that irrigation boosts agricultural production and has a beneficial influence on household income and poverty alleviation i.e. Bhattarai and Moorthy (2003); Smith (2004); Huang et al. (2006); Hussain et al. (2006); Tesfaye et al. (2008); Hagos et al. (2012); Haque (2015); Amede (2015); Tefera and Cho (2017); Gidey (2020); Rizal et al. (2021). Dhawan (1988), believe that because there is no economic theory of irrigation and its effects, empirical data are judged against researchers’ prior thinking, which generates great uncertainty when the outcomes of an empirical inquiry contradict expectations. The lack of consensus on the relationship between irrigation and poverty reduction appears to reflect the broader dispute concerning agriculture’s role in economic development processes (Diao et al., 2007). For example, Christiaensen et al. (2006) claim that, whereas most impoverished people in low and middle-income nations, notably in Sub-Saharan Africa rely directly on agriculture, for their livelihood. There is no universal agreement on the importance of agriculture in socioeconomic development and poverty reduction.

The methodology also has an impact on the findings of the impacts of irrigation development on family poverty. Regional studies seldom discover substantial correlations between irrigation investment and social and economic development. Pender et al. (2000) investigated the impact of irrigation projects in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, and discovered significant improvements in terms of increased output due to these projects. Owusu et al. (2011) investigate the effects of sufficient availability of irrigation water on poverty alleviation in the Savannah area of Ghana. The research reveals an enhanced agricultural income and suggests that irrigation projects be built to relieve poverty. Hussain et al. (2006) studied the effects of irrigation development on poverty alleviation in peri-urban districts of Punjab. The study suggests that rain-fed farmland has a greater poverty rate than irrigated farmland. Ashraf et al. (2004, 2007), assessed the influence of Dhok Sandaymar, Jawa, and Khasala dams on the dam command area in Punjab. The research revealed increased cropping and land-use intensity, yield, and production. Moreover, it show that increase in farm income and also determines that the water table rose in the command areas of the dams.

Palai dam is constructed some 16 km from Tangi town and 40 km north of Charsadda city on river Jindai. It is geographically located at 34°-26 N latitude and 71°-41′E longitude (Figure 1). The dam’s construction began in 2009 and was finished in 2011. It has a catchment area of approximately 142.45 km2 and is intended to have a command area of 4600 acres (GoKP, 1994). The dam’s primary role is to supply water to 4,600 acres of farmland in four communities of district Charsadda. A total of 30 cubic feet per second (cfs) water is scheduled to be provided to two feeding canals. The right bank canal is 3.5 km long and gets 6.5 cubic feet per second of water, which irrigates 1000 acres of land. The left bank canal is 11.7 km long and gets 23.5 cubic feet of water per second from the dam, which is meant to irrigate 3680 acres of land. Prior to the dam’s construction, just 125 acres of agricultural land were irrigated by lift irrigation from the Jindai River, with the remainder being rainfed agriculture. According to the administration, cultivation intensity of 130 percent was predicted by 2016, GoKP (1994).

The current study’s goal is to look at the socioeconomic impact of the Palai Dam on the communities of Qilla and Nasratzai. Qilla is a tiny hamlet in Tehsil Tangi, District Charsadda that is under the jurisdiction of the Palai dam. Mohammand agency is located to the west of village Qilla. District Malakand is located to the north, village Palai Nasratzai to the south, and village Dobandai is to the east. Geographically, the settlement is situated between 34°03,05″ to 34°28′ 00″ N latitude and 71°20, 00″ to 71°28′00″ East longitudes. The community of Palai Nasratzai is located in the south of village Qilla in tehsil Tangi district Charsadda. Geographically it lies between 34°, 24, 20″ to 34° 24′40″ N latitude and 71°,40,20″ to 71°,41,00″ E longitude. Both communities are agricultural, with virtually every home owning a plot of land. Wheat, tomato, onion, and vegetables are the major crops (GoP, 2000). Figure 1 depicts the research area’s location.

Materials and Methods

The present research is empirical in nature demonstrated with both primary and secondary data. Secondary data regarding crops grown in Kharif and Rabi season, area under different crops before and after dam construction, irrigated area, type of irrigation, etc. was acquired from revenue office Tangi, district Charsadda. The collected data was then used to determine the area under different crops before and after dam construction which in turn was utilized to compute the revenue generated before and after dam construction. The following steps were involved in the methodology:

- Scanning of Cadastral map of both the villages and subsequently imported to ArcMap 10.2.1, followed by geo-referencing in the projected coordinate system (WGS-1984 UTM Zone 42N)

- Creation of Geodatabase and subsequent creation of feature class with village name, geometry type Polygon projection UTM Zone 42N.

- Digitization of parcels and revenue data entry in attribute table connected to parcels i.e. Crop type in 2008-09 and 2016-17.

- Cross attribute table operation to calculate the changes that took place from 2008-09 to 2016-17 in the area under different irrigation sources, and area under different crops.

- Preparation of various maps showing Rabi and Kharif crops. Figures 2A, B, 3A, B, 4A, B, 5A, B show Rabbi crops 2008-09 and 2016-17 and Kharif crops 2008-09 and 2016-17 of both villages Palai Nasratzai and village Qilla, respectively.

Table 1: Selected villages total population, no of household and sample size.

|

Name of village |

1998 census |

2017 census |

|||

|

Total population |

Total No of household |

Total population |

Total No of household |

Sample size |

|

|

Palli Nasrat Zai |

1,982 |

231 |

3680 |

494 |

100 |

|

Qilla |

1,092 |

114 |

1035 |

108 |

58 |

The primary data regarding household characteristics and socio-economic conditions including spending on health and education, occupation and housing condition, etc. were gathered using a pre-tested structured questionnaire and focus group discussion. The questionnaire is developed to analyze the impact of the Palai Dam Project on two selected villages i.e. Pali Nasratzai and Qilla. The data was collected from individuals with an average age of 45. Focus group discussions (FGDs) were held with revenue officials and elders from the research region to validate and corroborate the findings.

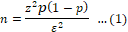

According to the 1998 census, the total population of both villages was 3074 with 345 households. The average household size was 8.9 (GoP, 2000). According to the 2017 census, the population of both villages increases to 4,715, with a total of 602 households. The average household size is 7.8 (GoP, 2018). The sample size is determined by Equation 1, Naing et al. (2006).

Where; z is the z score, ε is the margin of error, N is the population size and p̂ is the population proportion.

According to Equation 1, with a confidence level of 75 percent (z score of 1.28), 50percent proportion of the population, 5.2percent margin of error, the sample size for two selected villages is given in Table 1. For field surveys, the current study employed a purposive sampling approach. Purposive sampling is the most often used approach in qualitative research for identifying and selecting informative respondents (Patton, 2002; Mustafa et al., 2018). Almost all the respondents have agricultural land and practice agriculture. A total of 100 respondents were surveyed in Pali Nasratzai and 55 in village Qilla.

Results and Discussion

Provision of irrigation water has a positive effect on growth, benefiting the poor farmers as well as poor landless in long run in both relative and absolute terms. The progress in irrigation technologies, such as delay action dams (DAD), the building of small irrigation dam construction, micro-irrigation systems has firm anti-poverty potential (Hussain and Hanjra, 2004; Hanjra et al., 2009; Tolera, 2019).

The majority of respondents surveyed had been engaged in agriculture for 40 to 50 years and had noticed changes in agricultural practice and patterns as a result of the availability of enough irrigation water after dam construction. By bringing cultivable wasteland under the plough and boosting agricultural productivity and production in the area, this dam proved to be a significant source of income. As a result of the construction of the dam, new crops have also been introduced to the region, including onion and sugarcane in village Qilla. Due to the increased availability of irrigation water, farmers may now make more money than ever before.

Ex-post impact of Palai Dam on revenue generation

The primary source of revenue in both localities has always been agriculture. The main crops in the study region include wheat, maize, sugar cane, onion, tomato, and cucumber. All of these crops were grown locally prior to the dam’s construction to ensure self-sufficiency with minimal to no commercialization. According to field survey wheat production per acre was 1450 kilograms (Kg) before dam construction, and it jumped to 2300 kg after dam construction. Responses indicate that the adoption of high-yielding wheat varieties and the availability of adequate water are the main causes of this increase in production.

Based on the 2008 price per kg of PKRs. 16, it was projected that the total revenue from wheat for Palai Nasratzai would be PKRs. 23,200. In 2008–09, there were 2241 acres of land that was planted to wheat. A total of PKR 51991200 was earned from wheat. The wheat revenue per family was calculated to be PKRs. 225070 for a total of 231 households (census of 1998). This income rose to Rs. 250,732/household in 2016–17. Tables 2 and 3 show the revenue generated by different Rabi and Kharif crops in the Pali Nasrat Zai before and after the construction of the dam. Tables 4 and 5 show the revenue generated by the various Rabi and Kharif crops in the community of Qilla before and after the construction of the dam.

Reviewing Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 reveals that during the Kharif and Rabi seasons, a large rise in the area planted with all major crops was seen. As a result, both Village Qilla and Palai Nasratzai had a considerable gain in revenue. A field study and data analysis in ArcMap 10.2 revealed that, before the dam’s construction in Palai Nasratzai, the income per family from both the Kharif and Rabi crops was PKR 488511.68 (or PKR 56935.51/Capita), and that it climbed to PKR 1089252.42 (or PKR 146220.29/Cipita) following the dam’s completion in 2016–17. The net revenue roughly doubled once the dam was completed. After the dam was completed, the net per household income from the combined Rabi and Kharif crops in Village Qilla climbed to PKRs. 66541.74 (PKRs. 6943.38/capita), from PKRs. 33796.05 (PKRs. 3528.16/capita) in 2008-2009.

The healthcare situation of the studied region before and after dam building

It is true that wherever revenue is produced, it will unquestionably have an effect on the community’s housing, economic standing, and access to healthcare, education, and other services. The field survey and focus group discussions (FDG’s) revealed that in both villages’ the health conditions improved with rising per capita income. After the Pali Dam was completed, it seems that people are spending more on health-related issues.

Table 2: Pali Nasrat Zai, revenue generated from Rabbi Crops 2008-09 and 2016-17.

|

|

Wheat |

Onion |

||

|

2008-09 Before Dam |

2016-17 After Dam |

2008-09 Before Dam |

2016-17 After Dam |

|

|

♦ Per Acre Prod. /Kg (a) |

1450 |

2300 |

2600 |

4350 |

|

♦ Price per Kg (b) |

16 |

29 |

35 |

45 |

|

●Area under Crop (Acre) (c) |

2241 |

1857 |

221 |

722 |

|

Total Production in kg (a*c) |

3249450 |

4271100 |

574,600 |

3,140,700 |

|

Total revenue in PKR. (d) (a*b*c) |

51991200 |

123861900 |

20,111,000 |

141,331,500 |

|

*Number of Households (e) |

231 |

494 |

231 |

494 |

|

Per household income (d/e) |

225070 |

250,732 |

87,060 |

286,096 |

|

Change PKR |

25662 |

199,036 |

||

|

*Population (f) |

1982 |

3680 |

1982 |

3680 |

|

Revenue /Capita (d/f) |

26231 |

33658 |

10146 |

38405 |

|

Change PKR/capita |

7427 |

28259 |

||

*1998 and 2017 households and population acquired from district census reports. ● The area under crops acquired from revenue record 2008-09 and 2016-17. ♦ Acquired through fieldwork. Source field survey, 2017 and GOP, 1998, 2017.

Table 3: Palai Nasrat Zai, revenue generated from Kharif crops 2008-09 and 2016-17.

|

|

Maize |

Sugarcane |

Cucumber |

Tomato |

||||

|

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-9 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

|

|

♦ Per Acre Prod. /Kg (a) |

1200 |

1850 |

1900 |

3050 |

1150 |

1950 |

1250 |

1850 |

|

♦ Price per Kg (b) |

15 |

27 |

45 |

70 |

35 |

40 |

45 |

50 |

|

●Area under Crop (Acre) (c) |

133 |

374 |

89 |

953 |

167 |

251 |

427 |

337 |

|

Total Production in kg (a*c) |

159600 |

691900 |

169100 |

2906650 |

192050 |

489450 |

533750 |

623450 |

|

Total revenue in PKR(d) (a*b*c) |

2394000 |

18681300 |

7609500 |

203465500 |

6721750 |

19578000 |

24018750 |

31172500 |

|

*Number of Households (e) |

231 |

494 |

231 |

494 |

231 |

494 |

231 |

494 |

|

Per household income (d/e) |

10363 |

37816 |

32941 |

411873 |

29098 |

39631 |

103977 |

63102 |

|

Change PKR |

27453 |

378932 |

10533 |

-40875 |

||||

|

*Population (f) |

1982 |

3680 |

1982 |

3680 |

1982 |

3680 |

1982 |

3680 |

|

Revenue /Capita (d/f) |

1208 |

5076 |

3839 |

55290 |

3391 |

5320 |

12118 |

8471 |

|

Change PKR/capita |

3869 |

51450 |

1929 |

-3648 |

||||

*1998 and 2017 households and population acquired from district census reports. ● The area under crops acquired from revenue record 2008-09 and 2016-17. ♦ Acquired through fieldwork. Source field survey, 2017 and GOP 1998, GOP, 2017.

Table 4: Qilla, revenue generated from Rabbi crops 2008-09 and 2016-17.

|

|

Wheat |

Onion |

||

|

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

|

|

♦ Per Acre Prod. /Kg (a) |

1450 |

2300 |

2600 |

4350 |

|

♦ Price per Kg (b) |

16 |

29 |

35 |

45 |

|

●Area under Crop (Acre) (c) |

58 |

70 |

4● |

12● |

|

Total Production in kg (a*c) |

84100 |

161000 |

10400 |

52200 |

|

Total revenue in PKR. (d) (a*b*c) |

1345600 |

4669000 |

36400 |

2349000 |

|

*Number of Households (e) |

114 |

108 |

114* |

108** |

|

Per household income (d/e) |

11804 |

43231 |

319 |

21750 |

|

Change PKR |

31428 |

|||

|

*Population (f) |

1092 |

1035 |

1092* |

1035** |

|

Revenue /Capita (d/f) |

1232 |

4511 |

33 |

2270 |

|

Change PKR/capita |

3279 |

2236 |

||

*1998 and 2017 households and population acquired from district census reports. ● The area under crops acquired from revenue record 2008-09 and 2016-17. ♦ Acquired through fieldwork. Source field survey, 2017; GOP, 1998, 2017.

Table 5: Qilla, revenue generated from Kharif Crops 2008-09 and 2016-17.

|

|

Sugarcane |

Tomato |

Vegetables |

|||

|

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

2008-09 Before dam |

2016-17 After dam |

|

|

♦ Per Acre Prod. /Kg (a) |

1200 |

3050 |

1250 |

1850 |

1300 |

1850 |

|

♦ Price per Kg (b) |

45 |

70 |

45 |

50 |

40 |

45 |

|

●Area under Crop (Acre) (c) |

0 |

17 |

43 |

52 |

1 |

11 |

|

Total Production in kg (a*c) |

0 |

51850 |

53750 |

96200 |

1300 |

20350 |

|

Total revenue in PKR. (d) (a*b*c) |

0 |

3629500 |

2418750 |

4810000 |

52000 |

915750 |

|

*Number of Households (e) |

114 |

108 |

114 |

108 |

114 |

108 |

|

Per household income (d/e) |

0 |

33606 |

21217 |

44537 |

456 |

8479 |

|

Change PKR |

33606 |

23320 |

8023 |

|||

|

*Population (f) |

1092 |

1035 |

1092 |

1035 |

1092 |

1035 |

|

Revenue /Capita (d/f) |

0 |

3507 |

2215 |

4647 |

48 |

885 |

|

Change PKR/capita |

3507 |

2432 |

837 |

|||

*1998 and 2017 households and population acquired from district census reports. ●The area under crops acquired from revenue record 2008-09 and 2016-17. ♦ Acquired through fieldwork. Source field survey, 2017 and GOP, 1998, 2017.

The survey results revealed that more respondents now use private medical services than they did before the dam construction. A question on the impact of the Palai dam construction on the overall health of the study area was asked during the field survey. The results show that within Pali Nasratzai, 57 percent of all participants agreed that their health has improved as a consequence of more money being spent on and access to private healthcare, 12 percent stated that they were content with their health, and the remaining 31 percent think there has been no change in their healthcare situation since the construction of the dam. The results of the survey, which are summarized in Table 6, were almost identical in the village of Qilla.

Table 6: Impact of Palai Dam on health condition of the respondents in the study area.

|

Health condition |

Pali Nasrat Zai |

Village Qilla |

||

|

No. of respondents |

% of total respondents |

No. of respondents |

% of total respondents |

|

|

Improved/ Good |

57 |

57 |

24 |

43.63 |

|

Bad |

31 |

31 |

13 |

23.63 |

|

Satisfactory |

12 |

12 |

18 |

32.72 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

Source: Field survey 2017

Impact of Dam on the education of respondents children’s

Before the dam was built, there were two public schools and one private school in Palai Nasratzai. However, the number of private schools increased to four once the dam was completed. Before the dam was built, the majority of respondents children (60 percent of all respondents children) attended public schools, while only 20 percent of respondents children attended private schools, and the other 20 percent of respondents children were not sent to school at all. Following the dam’s completion, 54 percent of children were enrolled in private schools, 32 percent in government schools, and 14 percent were not enrolled in any school.

Table 7: The housing condition of the study area before and after the construction of the dam.

|

Housing conditions |

Census |

Field survey |

||||

|

1998 |

Percentage |

2008-09 |

Percentage |

2017 |

Percentage |

|

|

Palai Nasrat Zai |

||||||

|

Kacha |

72 |

31 |

70 |

70 |

40 |

40 |

|

Semi Pacca |

02 |

01 |

08 |

08 |

13 |

13 |

|

Pacca |

157 |

68 |

22 |

22 |

47 |

47 |

|

Total |

231 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Village Qilla |

||||||

|

Kacha |

107 |

93 |

30 |

54 |

15 |

27 |

|

Semi Pacca |

04 |

04 |

02 |

04 |

05 |

09 |

|

Pacca |

03 |

03 |

23 |

42 |

35 |

64 |

|

Total |

114 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

Source: Field survey 2017 and GOP, 2000

Similar outcomes were noted in Qilla, a village with just one public school and two private schools, in the academic year 2008–09. In contrast, the number of private schools rises to three and the number of government schools to two in 2015–16. According to the findings of the field survey, 57 percent of respondents’children were enrolled in public schools, 27 percent were enrolled in private schools, and 16 percent were not enrolled at all. Nevertheless, the percentage of kids attending private schools increased to 47%, the percentage attending government schools to 33%, and the percentage of not enrolled students to 20% after the Dam construction. The results of the field survey and FDGs indicate that residents’ preferences for education increase as net wealth increases and most of respondents are increasingly making financial investments in education by putting their children in private schools.

Impact of dams on the housing conditions in the study region

Another key socioeconomic factor to study the impact of the dam was the change in respondents’ housing conditions before and after the dam construction. According to a field study conducted in the hamlet of Pali Nasrat Zai, 22 percent of respondents dwellings were Pakka, 70 percent were Kachha, and the remainder 08 percent were semi-pucca buildings prior to the dam’s construction. However, when the dam was built, the number of Pakka homes rose, with 47 percent of total respondents now having Pakka houses, 40 percent still having Kachha, and 13 having partly Pacca houses. Prior to dam construction, 42 percent of respondents in Village Qilla had Pacca homes, 54 percent had Kachha houses, and 04 percent had Semi Pacca buildings. Following dam building, 64 percent of respondents now live in Pacca homes, while 27 percent still live in Kachha dwellings.

Respondents’ family status before and after dam completion

The Palai dam had an influence on another variable used to analyze the socio-economic impact of the dam on the respondents family status, i.e. whether they have a joint family or live as a single-family. This indicator is based on the assumption that poor families choose to live in a joint family structure to meet expenditures. According to a field survey prior to dam completion, 52 percent of respondents’ families were living as joint, 49 percent as single, and 13 percent as extended family. However, after dam completion, 39 percent of respondents were now living as joint, 51 percent as single, and only 10 percent as extended family. Table 8 displays the results.

Table 8: Family status of the study area before and after the construction of dam.

|

Housing conditions |

2008 |

Percentage |

2017 |

Percentage |

|

Palai Nasrat Zai |

||||

|

Single family |

35 |

35 |

51 |

51 |

|

Joint family |

52 |

52 |

39 |

39 |

|

Extended family |

13 |

13 |

10 |

10 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Village Qilla |

||||

|

Single family |

30 |

55 |

20 |

37 |

|

Joint family |

02 |

03 |

02 |

03 |

|

Extended family |

23 |

42 |

33 |

60 |

|

Total |

55 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

Source: Field survey 2017.

Impact of dam on the respondent’s occupation in the study area

Occupation is also an excellent indication of a community’s affluence and socioeconomic status. During the field, a question concerning the sort of profession and people’s proclivities toward off-farm work in the Ex-Post scenario of the Palai Dam was posed. According to the field survey, just 25 percent of respondents were involved in farming or on-farm work in 2008-09, which increased to 39 percent in 2017. According to respondents, prior to dam construction, due to a lack of irrigation water, a large portion of the cultivated area remained fallow, resulting in net revenue from farming that was insufficient to sustain a living. As a result, the responders must complement their agricultural income with off-farm work. In terms of Village Qilla, the field survey yielded very identical results. The survey findings are summarized in Table 9. According to the findings, respondents’ reliance on agriculture rose with the building of the Palai dam. Despite having agricultural land, the lack of sufficient irrigation water, they were forced to live hand to mouth. With enough irrigation water, the area under Kharif and rabi crops (Tables 2, 3, 4, 5) expanded dramatically, and agriculture is now a viable activity in both communities. Aside from that, sugarcane was absent from the fields in 2008-09 but has since become a key revenue crop in 2017. Irrigation water transforms agriculture from sustenance to commercial and market-oriented, and it becomes a source of consistent revenue.

Table 9: Occupation in the study area.

|

Occupation |

2008-09 |

%age in 2008-09 |

2017 |

%age in 2015-16 |

|

Pali Nasrat Zai |

||||

|

Farming |

25 |

25 |

39 |

39 |

|

Teaching |

33 |

33 |

29 |

29 |

|

General Labor |

29 |

29 |

24 |

24 |

|

Others |

13 |

13 |

8 |

8 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

Village Qilla |

||||

|

Farming |

11 |

20 |

21 |

38 |

|

Teaching |

25 |

45 |

26 |

29 |

|

General Labor |

09 |

16 |

11 |

20 |

|

Others |

10 |

18 |

7 |

13 |

|

Total |

55 |

100 |

55 |

100 |

Source: Field survey 2017.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The study concludes that there has been a noteworthy increase in farmer’s earnings from both Kharif and Rabi crops in both communities since the completion of the Palai Dam. The money earned from both the Rabi and Kharif crops rose as a result of the Palai irrigation canal’s construction, which influences the socioeconomic status of the studied region. The study suggests that prior to the building of the dam in Palai Nasratzai, the total revenue earned per family from both Kharif and Rabbi crops was PKRs, 488511.68 (PKRs. 56935.51/capita), which increased to PKRs. 1089252.42 (PKRs. 146220.29/capita) after the dam was completed in 2016-17. After the dam was built, the net income nearly quadrupled. In Village Qilla, the net per family income from combined Rabi and Kharif crops in 2008-09 was PKRs.33796.05 (PKRs. 3528.16 /capita), which increased to PKRs. 66541.74 (PKRs. 6943.38/capita) after the dam was built. This rise in net income is mirrored in both villages socioeconomic conditions. The neighborhood experienced an increase in the number of private schools. People are increasingly turning to private medical care following the dam’s completion, the number of Pacca homes grew as well. The assessment of revenue records and primary data obtained indicates that the Palai dam has a substantial influence on selected communities. The same sort of influence was observed in both villages; however, the impact is more noticeable in one of the larger settlements, Palai Nasratzai. Tube wells and rainfed irrigation were the primary sources of irrigation in both villages prior to dam building.

However, since the dam’s completion, canal irrigation has accounted for more than half of the irrigated area. This has a significant impact on the cropping patterns of the selected communities. The conventional cropping system underwent yield modifications as a result of adequate water availability. With the addition of sugarcane in Kharif and Onion in Rabi, farming has now been commercialized. The research indicates that dams like the Palai dam are much desired and suggests that smaller dams be built wherever they are needed in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. However, appropriate irrigation water management is strongly advised. Both the communities studied can increase crop productivity.

Novelty Statement

The research brings novelty by examining the impact of a small dam on the poverty alleviation of the communities located in the dame command area. The study quantitatively determines the increase in per capita income as a result of sufficient water availability after the construction of the dam.

Author’s Contribution

Muhammad Jamal Nasir: Supervised the research, analysis and discussion. Draft of the manuscript.

Anwar Saeed Khan: Statistical data analysis, and major findings.

Atiq Ur Rahman: Designing of research methodology.

Waqar Akhtar: Helped in field work and data collection.

Hafizullah Khan: Thematic mapping and explanation.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Amede, T., 2015. Technical and institutional attributes constraining the performance of small-scale irrigation in Ethiopia. Water Resou. Rural Dev., 6: 78-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wrr.2014.10.005

Ashraf, M., M.A. Kahlown and A. Ashfaq. 2004. Impact evaluation of water resources development in the command areas of small dam. Pak. J. Water Resour., 8(1): 23-38.

Ashraf, M., M.A. Kahlown and A. Ashfaq. 2007. Impact of small dams on agriculture and groundwater development: A case study from Pakistan. Agric. Water Manage., 92(1-2): 90-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2007.05.007

Awulachew, S.B. and D.J. Merrey. 2007. Assessment of small scale irrigation and water harvesting in Ethiopian agricultural development. International Water Management Institute (IWMI), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Balana, B.B., J.C. Bizimana, J.W. Richardson, N. Lefore, Z. Adimassu and B.K. Herbst. 2020. Economic and food security effects of small-scale irrigation technologies in northern Ghana. Water Resour. Econ., 29: 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wre.2019.03.001

Bhattarai, M. and A.N. Moorthy. 2003. Irrigation impact on agricultural growth and poverty alleviation: Macro level impact analyses in India. In: IWMA–Tata Workshop, January, 2003.

Christiaensen, L., L. Demery and J. Kuhl. 2006. The role of agriculture in poverty reduction an empirical perspective. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4013

Dhawan, B.D., 1988. Irrigation in India’s agricultural development: Productivity, stability, equity (No. 45). Sage Publications (Pvt) Ltd.

Diao, X., P.B. Hazell, D. Resnick and J. Thurlow. 2007. The role of agriculture in development: Implications for Sub-Saharan Africa. Intl Food Policy Res Inst. Vol. 153.

Fan, S., L. Zhang and X. Zhang. 2000. Growth and poverty in rural China: The role of public investments (No. 581-2016-39487).

Garbero, A. and T. Songsermsawas. 2018. Impact of modern irrigation on household production and welfare outcomes: Evidence from the Participatory Small-Scale Irrigation Development Programme (PASIDP) project in Ethiopia. IFAD Res. Ser., (31): 1-47.

Gebregziabher, G., R.E. Namara and S. Holden. 2009. Poverty reduction with irrigation investment: An empirical case study from Tigray, Ethiopia. Agric. Water Manage., 96(12): 1837-1843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2009.08.004

Gidey, G., 2020. Impact of small scale irrigation development on farmers livelihood improvement in Ethiopia: A review. J. Resour. Dev. Manage., 62: 10-18.

GoKP, 1994. Palai Dam Project, Feasibility Report. Peshawar Irrigation Department, Small Dams Directorate, Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

GoP, 2000. District Census Report, Charsadda. Population census organization statistics division, Government of Pakistan Islamabad.

GoP, 2018. Population and household detail from block to district level: Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Charsadda District) (Pdf). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Government of Pakistan Islamabad. (2018). Retrieved 23 April 2020 from http://www.pbs.gov.pk/content/block-wise-provisional-summary-results-6th-population-housing-census-2017-january-03-2018

Hagos, F., G. Jayasinghe, S.B. Awulachew, M. Loulseged and A.D. Yilma. 2012. Agricultural water management and poverty in Ethiopia. Agric. Econ., 43: 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2012.00623.x

Hanjra, M.A., T. Ferede and D.G. Gutta. 2009. Reducing poverty in sub-Saharan Africa through investments in water and other priorities. Agric. Water Manage., 96(7): 1062-1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2009.03.001

Haque, S., 2015. Impact of irrigation on cropping intensity and potentiality of groundwater in Murshidabad District of West Bengal, India. Int. J. Ecosyst., 5(3A): 55-64.

Higginbottom, T.P., R. Adhikari, R. Dimova, S. Redicker and T. Foster. 2021. Performance of large-scale irrigation projects in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat. Sustain., 4(6): 501-508. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00670-7

Huang, Q., S. Rozelle, B. Lohmar, J. Huang and J. Wang. 2006. Irrigation, agricultural performance and poverty reduction in China. Food Policy, 31(1): 30-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2005.06.004

Hussain, I. and M.A. Hanjra. 2004. Irrigation and poverty alleviation: Review of the empirical evidence. Irrig. Drain., 53(1): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ird.114

Hussain, M., Z. Hussain and M. Ashfaq. 2006. Impact of small scale irrigation schemes on poverty alleviation in marginal areas of Punjab, Pakistan. Int. Res. J. Finan. Econ., 6(6).

Kassam, A., W. Stoop and N. Uphoff. 2011. Review of SRI modifications in rice crop and water management and research issues for making further improvements in agricultural and water productivity. Paddy Water Environ., 9(1): 163-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-011-0259-1

Mustafa, K., M.C. Oguz, A. Kan, H. Ergun and E. Demiroz. 2018. Multidimensions of poverty for agricultural community in Turkey: Konya province case. Pak. J. Agric., 55(1). https://doi.org/10.21162/PAKJAS/18.5600

Naing, L., T. Winn and B.N. Rusli. 2006. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. J. Orofac. Sci., 1: 9-14.

Namara, R.E., M.A. Hanjra, G.E. Castillo, H.M. Ravnborg, L. Smith and B.V. Koppen. 2010. Agricultural water management and poverty linkages. Agric. Water Manage., 97(4): 520-527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2009.05.007

Owusu, E.S., R.E. Namara and J.K. Kuwornu. 2011. The welfare-enhancing role of irrigation in farm households in northern Ghana. J. Int. Divers, 1: 61-87.

Patton, M.Q., 2002. Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd Ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pender, J. and B. Gebremedhin. 2004. Impacts of policies and technologies in dryland agriculture: Evidence from northern Ethiopia. Challenges and Strategies of Dryland Agriculture, (challengesandst), pp. 389-416. https://doi.org/10.2135/cssaspecpub32.c24

Pender, J., P. Jaggera and B. Gebremedhinb. 2000. Agricultural change and land management in the highlands of Tigray: Causes and implications. Policies Sustain. Land Manage. Highl. Ethiopia, pp. 24.

Rizal, A., E. Rochima., M. Rahmatunnisa and B. Muljana. 2021. Impact of irrigation on agricultural growth and poverty alleviation in West Java Province, Indonesia. Sci. World J., 151: 64-77.

Saleth, R.M., R.E. Namara and M. Samad. 2003. Dynamics of irrigation-poverty linkages in rural India: Analytical framework and empirical analysis. Water Policy, 5(5-6): 459-473. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2003.0029

Smith, L.E., 2004. Assessment of the contribution of irrigation to poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods. Int. J. Water Resour. D, 20(2): 243-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/0790062042000206084

Songging, J., S. Huang, J.R. Hu and S. Rozelle. 2002. The creation and spread of technology and total factor productivity in China’s agriculture. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 84(4): 916-930. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8276.00043

Tefera, E. and Y.B. Cho. 2017. Contribution of small scale irrigation to households income and food security: Evidence from Ketar irrigation scheme, Arsi Zone, Oromiya Region, Ethiopia. Afr. J. Bus. Manage., 11(3): 57-68. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2016.8175

Tesfaye, A., A. Bogale, R.E. Namara and D. Bacha. 2008. The impact of small-scale irrigation on household food security: The case of Filtino and Godino irrigation schemes in Ethiopia. Irrig. Drain. Syst., 22(2): 145-158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10795-008-9047-5

Tolera, T., 2019. The problems, opportunities and implications of small scale irrigation for livelihood improvement in Ethiopia. A review. Civil. Environ. Res., 9: 12, 2017.

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?