Women Farmers’ Access to and Control Over Farming Resources and their Role in Decision Making Process in the Rural Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Research Article

Women Farmers’ Access to and Control Over Farming Resources and their Role in Decision Making Process in the Rural Areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Mehnaz Safdar1, Urooba Pervaiz1* and Dawood Jan2

1Department of Agricultural Extension Education and Communication, The University of Agriculture Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; 2Institute of Business and Management Sciences (IBMS), The University of Agriculture Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan.

Abstract | The current research was intended to investigate the access and control over farm input resources by the women farmer and their involvement in decision making in rural areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP)-Pakistan. Three districts namely Bannu, Swabi and Swat from KP were purposively selected and a sample size of 384 women farmers were selected through multistage sampling technique. Descriptive analysis revealed that 305 women farmers were involved in rearing poultry. A 5 point Likert scale was used, showed that women farmers had various constraints out of which Pardah, mobility and lack of information source were ranked on top with Likert score value of 4.12, 4.00 and 3.94, respectively. Due to male dominant society, 62.8% of the decisions were taken by spouse. Results of Chi-square analysis showed a significant association for age and decision making which means with increasing age of the women, their involvement in decision making increases, majority of the rural women were either not taking interest or not given the opportunity of decision making process of farming and family matters. Rural women have less access to farm inputs and less income generating opportunities. It is concluded that non-availability of timely technical knowledge and extension services, low family income, less access to farm inputs and inadequate income generating opportunities were the major constraints. Women farmers should be given easy and quick opportunity to open bank account, credit facilities and agriculture inputs and extension services.

Received | August 17, 2020; Accepted | May 19, 2021; Published | July 03, 2021

*Correspondence | Urooba Pervaiz, Department of Agricultural Extension Education and Communication, The University of Agriculture Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan; Email: [email protected]

Citation | Safdar, M., U. Pervaiz and D. Jan. 2021. Women farmers’ access to and control over farming resources and their role in decision making process in the rural areas of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 37(3): 930-941.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2021/37.3.930.941

Keywords | Women, Decision making, Agriculture and livestock, Extension services

Introduction

In rural areas of Pakistan, Agriculture is the main source of income as this sector accommodates almost 67% of the rural labour force (Sanaullah and Pervaiz, 2019). In Pakistan the main draw backs in this sector are the unequal distribution of cultivable land, disguised unemployment and conventional cultivation procedures resulting in low production (Akram et al., 2011). Women are contributing in almost every field of life but still they have more restrictions in accessing productive resources, markets and services (Damisa et al., 2007; Singh and Vinay, 2012). This “gender biasness” in the society hampers them in getting good production and reduces their share in the agriculture sector and in the attainment of wider financial social development goals. Minimizing the gender differences in the society can have positive effect on agriculture production, ensure food security and boosts economic development (Patil and Babus, 2018).

In the development and growth of rural and national economies women’s role is vital (Badiger and Huilgal, 2004). Mostly rural area’s women are contributing in the income of the family. Rural women’s key profession is agriculture and their immense hard work guarantees their independence (Sharma et al., 2014). Thus, they ought to be given good opportunity and right to utilize natural assets for the expectations’ modification and mitigation of climatic change and their skills must be enhanced with in the cultural limitation for the adaptation of modern technology (Praveena, 2005).

Women holds central position in the economic prosperity of any country but their participation differs from area to area and country to country and to little amount on the various stages of development and growth and to large extent on their traditional civilization (Amin et al., 2009; Akter et al., 2017). Regrettably, in Pakistan because of low education and societal and cultural restrictions, women labor force can’t be used to its high potential in economic practices (Pervaiz et al., 2012). Formerly female were bound to perform their duties within the four walls of a house as a mother and wife but now new reforms of the societies are demanding new role from the women. Economic and financial crises have forced female to work beside male in earning of living in under developed countries (Zia, 2000). Women are not given the opportunity of getting quality education and their responsibilities are limited to household activities (Akter et al., 2017). Most of the developmental projects are launched without active involvement and participation of women and as a result woman can’t be benefited from these projects and programs (Amin et al., 2009). Women are basically working or searching for employment in agriculture and non-agriculture sector to meet the family needs and increase income (Nazly et al., 2004; Mugede, 2013; Anaglo et al., 2014; Anderson et al., 2017).

In the developing countries, societies are male dominant and men and women have different roles and responsibilities due to the conventional model of society (Pervaiz et al., 2012; Gebre et al., 2019). Due to this gender inequity women lack access to resources and cannot take part in new economic opportunities as compared to men (FAO, 2010). Women cannot purchase better agricultural inputs like chemical fertilizers, oxen, plough etc. due to non-availability of financial resources (Akter et al., 2017; Gebre et al., 2019). Only 2 percent of the women all over the world hold ownership of the land, usually they do not have the right in the inheritance of property (Steinzor, 2003). Likewise, gender differences in the society hinder the attainment of large financial and social growth objectives. This also has an effect on women’s share and production in the agriculture sector (Dillon and Quinones, 2010). Women mostly do the labor work by themselves as they do not have enough financial resources to hire labors. Main problems faced by women are the specific land and property rights (World Bank, 2008).

For obtaining better agriculture productivity, justifiable and equal sharing of the reproductive resources among men and women is vital but in most of the development projects launched for small farmers, women’s accessibility to resources is usually ignored (Quisumbing and Pandolfelli, 2010). Participation of men and women in agricultural activities is noteworthy but their opportunities to the reproductive resources varies (Deere and Doss, 2006; FAO, 2010; Bala, 2010; Singh and Vinay, 2012).

Objectives of the study were to identify women’s roles and responsibilities in agriculture and livestock, explore women’s access to and the control over these resources and to investigate the extent of women’s involvement in decision making related to agriculture and livestock.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The universe of the study was Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, it is situated at 34.45°N 71.7°E. Due to diverse agro-climatic conditions and topography, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province is divided into five Agro-Ecological Zones (AEZs). For the present research study four stages of multi sampling technique i.e. Zones, Districts, Tehsils, and Union Councils were adopted for the selection of sample. In Stage I: Selection of Agro- Ecological Zones were made, out of the total five zones, three zones i.e. Zone A, Zone C and Zone D were selected purposively. Zone B and E were skipped due to conservative nature and low accessibility. In Stage II: Selection of districts were made, one district was randomly selected from each zone, from Zone A; District Swat was randomly selected, from Zone C; District Swabi and from Zone D; District Bannu was selected randomly. In Stage III: Two tehsils were randomly selected from each selected district. In Stage IV: two union councils were randomly selected from each selected tehsil.

Sample size

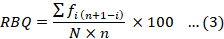

Women farmers were taken as the study respondents. For unknown population the sample size was collected on guess variability i.e. 50% for maximum sample size. The sample for the unknown population was obtained through formula.

Whereas N= Total size of sample; D= Estimate acceptable margins (5%); Z= Error of the confidence level limit or Normal variation (95%) and constant for this value is 1.96; V= Assumption of variability with regard of farmer’s locality which is (50%); N= (1.96)2× (50)2 / (5)2 = 384.

Total number of 384 women respondents were selected from the three districts by applying Equation 1. In order to get equal representation 384 respondents were divided equally on each district i.e. 384/3= 128. So, from each district 128 women respondent were taken.

It is pertinent to note that these Union Councils do not have formal data regarding women employment, the selection of sample was based on the selection of every 3rd house randomly. From each selected union council, those women (who were directly or indirectly involved in farming and/or livestock) were selected for data collection. If a woman was not involved in farming and/or livestock, that house was excluded and the next was selected.

Data collection tools

Primary data was collected through a well-structured interview schedule (Sanaullah and Pervaiz, 2019). The interview schedule was developed according to the study objectives. Secondary data were obtained from the web portal and research findings of other researchers (Khan et al., 2019; Sanaullah et al., 2020). Efforts were taken to keep the questionnaire simple and understandable. Questions were asked in local language to get the authentic information from the selected respondents .

Data analysis

The collected data was analyzed through Statistical Software (SPSS v.20) and the results were obtained in frequencies and percentages. A 5-point Likert scale was used to show various constraints women farmers were facing i.e. 1= strongly disagree 2= disagree 3= undecided 4=Agree 5= strongly agree.

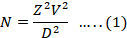

To find out the association among different variables Chi-Square test was applied with the following formula.

Formula for Chi-Square test statistics is as under:

This test under the null hypothesis (Hₒ) follows a x2-distribution with (r-1)(c-1) degrees of freedom, in Equation 2, Oij indicates the observed frequency and eij shows the expected frequency.

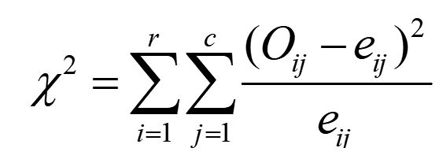

Ranked based quotient

Ranked Based Quotient (RBQ) technique was used to quantify the data collected by Preferential Ranking Technique. The following formula is given by Sabarathnam (1988).

Where; fi = Number of respondents reporting the ith rank; N= Number of respondents; i= Number of rank; n= Number of constraints identified.

Results and Discussion

Women in livestock/poultry

Women mostly use milk, eggs and poultry meat for their own household consumption and have strong control over the income they get from the marketing of these products. Maybe this is the reason large developmental projects focus on small scale poultry and dairy projects with the basic purpose to improve the life of rural women. Usually women have dominant role in poultry management (Guèye, 2000; Tung, 2005) and livestock (Tangka et al., 2000).

In Pakistan, rural areas women have strong contribution in poultry and livestock management. Table 1 represents the number of livestock animals and poultry owned by the respondents in the study area. The questions regarding livestock and poultry rearing were asked and their responses were recorded. One respondent can have many responses for multiple options in the question asked; therefore, total number of responses is presented which are more than total number of the respondents. The data regarding poultry in district Bannu revealed that 122 respondents had poultry out of 128, followed by cows owned by 111 respondents. In same way, 28 responses were about having buffalos, 38 household owned goats and 43 women responded they had sheep in their houses. In district Swabi, majority (97) responses were about rearing poultry hen, followed by poultry (87), buffalos (40), goats (23) and sheep (22). Accordingly, women in district Swat were interviewed regarding this question where 96 women household rear poultry hen, followed by cows (72), buffalo (33), goat (23) and sheep (17) respondents in their houses. Summing up the total responses, 305 respondents had reared poultry, followed by 280 responses who owned cow. This data depicts that women farmers also depends on livestock and poultry besides crop farming. The importance of cattle and poultry as shown by the ownership of these animals is an indication of its need and necessity for rural economy as well as for domestic uses.

Table 1: Sampled distribution regarding livestock/poultry they rear.

|

District |

Livestock/poultry reared |

Total |

||||

|

Buffalos |

Cows |

Goats |

Sheep |

Poultry |

||

|

Bannu |

28 |

111 |

38 |

43 |

122 |

342 |

|

Swabi |

40 |

97 |

30 |

22 |

87 |

276 |

|

Swat |

33 |

72 |

23 |

17 |

96 |

241 |

|

Total |

101 |

280 |

91 |

82 |

305 |

859 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Sale of livestock/poultry products

Rural women are dependent on their male members of the family for living. They don’t have any business involvement or proper govt. or private jobs to earn for themselves. But on small scale they can get income form sell of the own raised livestock and poultry. Therefore, data regarding sell of livestock/poultry products were collected and presented in Table 2. Milk, Desi ghee, eggs and chicks are local livestock/poultry products used domestically and sold for getting income. Multiple responses were responded by women in the selected three districts of KP. In district Bannu, 47 respondents responded that they sell milk, while desi ghee, eggs and chicks were sold by 68, 38 and 32 respondents respectively. Similarly, in district Swabi, 42 respondents reported they sold milk, followed by 45, 25 and 21 respondents who sold desi ghee, eggs and chicks, respectively. Likewise, in district Swat majority i.e. 51 respondents had sold desi ghee, milk by 36 respondents; eggs by 23 and 19 respondents reported that they sold chicks in the study area.

Table 2: Sampled distribution regarding selling the type of livestock/poultry products.

|

District |

Livestock/poultry products sold |

Total |

|||

|

Milk |

Desi ghee |

Eggs |

Chicks |

||

|

Bannu |

47 |

68 |

38 |

32 |

185 |

|

Swabi |

42 |

45 |

25 |

21 |

133 |

|

Swat |

36 |

51 |

23 |

19 |

129 |

|

Total |

125 |

164 |

86 |

72 |

447 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Income from sale of farm/ livestock/ poultry products

Information regarding income of the women was collected in the three selected districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Their income was presented in Table 3 and categorized in three categories i.e. up to Rs. 25000, 25001-50000 and above 50000. In district Bannu majority (13.8%) of the respondents were having income up to Rs. 25000 from various livestock/poultry products per season, followed by 10.2% respondents who had income above 50000, while 9.4% respondents were found having income between Rs. 25001-50000. Similarly, in district Swat, majority (15.9%) of the respondents had income up to Rs. 25000 from various livestock/poultry products per season, followed by 10.7% respondents who had income between Rs. 25001-50000, while 6.8% of the respondents were found having income above Rs. 50000. In district Swabi, 13.5% of the respondents had income up to Rs. 25000 from various livestock/poultry products per season, followed by 12.2% respondents who had income in range of 25001-50000, while 7.6% respondents were having income above Rs. 50000. Overall, 43.2% of the respondents had low income that is up to Rs.25000. It is due to the low skilled practices and modern farming information. Women in Pakistan are contributing in rural economic activities by performing in the sector of livestock, crop production and cotton industry besides their basic household responsibilities (Jamali, 2009).

Table 3: Distribution of sampled respondents regarding their income from selling of farm/livestock/poultry products.

|

District |

Income from selling of farm/livestock/poultry products (Rs.) |

Total |

||

|

Up to 25000 |

25001-50000 |

Above 50000 |

||

|

Bannu |

53(13.8) |

36 (9.4) |

39 (10.2) |

128 |

|

Swabi |

61(15.9) |

41 (10.7) |

26(6.8) |

128 |

|

Swat |

52(13.5) |

47(12.2) |

29(7.6) |

128 |

|

Total |

166(43.2) |

124 (32.3) |

94(24.5) |

384 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages.

Purchase of agricultural inputs

Table 4 shows data regarding various mixed questions. Initial two questions were asked in dummy while the third question was given in closed ended options. Out of the total 384 respondents, only 24.0% respondents had access to purchase agricultural inputs in which 88.5% reported that their husband supports them for purchase of agricultural inputs, the remaining 11.5% were either widows or divorced who were mostly self-supporting. Respondents were asked of market place for purchase of these inputs where 69.5% of the respondents had purchased necessary inputs from relatives, followed by 25.3% respondents who purchased inputs form neighbours and only 5.2% respondents who had access to local nearby market. Butt et al. (2010) recommended that government and extension department should work in collaboration to provide convenient market access to women in rural areas.

Sale of agricultural products

Table 5 shows distribution of the respondents regarding selling of farm products, buyers of farm products and control of money obtained from sell of farm products. It is concluded that 63.3% of the respondents did not sell agricultural products, while 36.7% respondents used to sell farm products. Of the total 384 respondents 14.8% of them sold their products to relatives, followed by 13.8% respondents who sold their products to local market, while 8.1% respondents were recorded who sold their products to other people anyone neighbours etc. Table 5 also shows data regarding control of money obtained from sell of agricultural products, 22.4% of the respondents responded that their husband control money obtained from selling agricultural products, followed by 7.6% respondents who reported that they themselves control the money, while 6.8% respondents were of the view that anyone else like family elder or son controls the money.

Table 4: Distribution of the respondents regarding purchase of agricultural inputs.

|

District |

Access to purchase agricultural inputs |

Spouse financial support to purchase these inputs |

Place of purchase |

||||

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Market |

Relatives |

Other farmers/ neighbours |

|

|

Bannu |

20(5.2) |

108(28.1) |

115(39.9) |

13(3.4) |

4(1.0) |

96(25.0) |

28(7.3) |

|

Swabi |

33(8.6) |

95(24.7) |

112(29.2) |

16(4.2) |

9(2.3) |

80(20.8) |

39(10.2) |

|

Swat |

39(10.2) |

89(23.2) |

113(29.4) |

15(3.9) |

7(1.8) |

91(23.7) |

30(7.8) |

|

Total |

92(24.0) |

292(76.0) |

340(88.5) |

44(11.5) |

20(5.2) |

267(69.5) |

97(25.3) |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages.

Table 5: Distribution of the respondents regarding sell of agricultural products.

|

District |

Sell farm products |

Buyers of farm products |

Control of money obtained from sell of agri. Products |

|||||

|

Yes |

No |

Market |

Relatives |

Any other |

Herself |

Husband |

Any other |

|

|

Bannu |

69(18.0) |

59(15.4) |

30(7.8) |

25(6.5) |

14(3.6) |

13(3.4) |

50(13.0) |

6(1.6) |

|

Swabi |

32(8.3) |

96(25.0) |

6(1.6) |

15(3.9) |

11(2.9) |

7(1.8) |

17(4.4) |

8(2.1) |

|

Swat |

40(10.4) |

88(22.9) |

17(4.4) |

17(4.4) |

6(1.6) |

9(2.3) |

19(4.9) |

12(3.1) |

|

Total |

141(36.7) |

243(63.3) |

53(13.8) |

57(14.8) |

31(8.1) |

29(7.6) |

86(22.4) |

26(6.8) |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages.

Female extension worker

Agricultural extension is termed as information delivery system aimed to transfer new findings of agricultural research to farming community. Well- organized and efficient communication is pre-requisite in any extension work (Yahaya, 2001).

Data in Table 6 show information about female extension worker in the three selected districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The study outputs revealed that all of the study respondents reported no female agriculture/livestock extension worker was available in their area. It means that female extension worker position does not exist in agricultural extension department in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Table 6: Availability of female extension worker and their need.

|

District |

Female extension worker available |

Need rank for female extension worker |

|

|

Yes |

No |

||

|

Bannu |

0 (0) |

128 (33.3) |

4.56 |

|

Swabi |

0 (0) |

128 (33.3) |

4.40 |

|

Swat |

0 (0) |

128 (33.3) |

3.98 |

|

Total |

0 (0) |

384(100) |

12.94 (4.31 average) |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages.

In the light of this field observation, there is dire need to establish female extension staff and ensure active participation of female farmers in field activities. For this reason, second question was asked from respondents about their need for these female extension field staff. A five-point Likert scale (denoting from strongly disagree to strongly agree where 1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: undecided, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree) was used to identify the eagerness for this demand. In district Bannu the average Likert scale value was 4.56 which is near to 5 (strongly agree), so means that women in Bannu were more enthusiastic towards female extension workers’ need in the area. District Bannu had the highest Likert scale value and it might be due to the reason that district Bannu is more conservative hard remote area in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where it is more likely for women to work under female extension worker instead of male. The mean Likert scale value measured for district Swabi was 4.40, ranked on second position out of the three districts. It was also near to strongly agree which means that women in Swabi showed strong willingness for the need of female extension worker. Similarly, average of 3.98 Likert scale value was estimated for district Swat. This computed value is near to agree which means that there is need for female extension staff in the area. The overall average Likert scale calculated was 4.31 which mean that almost all of the study respondents showed strong willingness for the need of female extension staff.

Similar results were recorded by Sadaf et al. (2006) who stated that access to information is a due right of both men and women farmers, but unfortunately in Pakistan, men’s access and control over the resources makes their roles and responsibilities different than women. Santra and Kundu (2001) also reported that women cannot respond to new opportunities due to lack of access to resources as compared to men because of gender biasness. In the context of the above discussion, government should take bold and appraisable decisions to formulate a separate female extension directorate under female Director General (DG) and all other female staff that will work in coordination with male directorate. In this way our agricultural system will be strengthened as mostly women are involved in various agricultural and farming practices in rural area for which they don’t have proper training or knowledge.

Constraints faced by respondents in livestock/poultry

Data concerning different problems/constraints faced by the women farmers while operating livestock/poultry activities were presented in Table 7 and it shows that maximum respondents i.e. 300 recorded low family income as their main constraint, 165 respondents stated that cattle disease is their major problem in livestock agriculture, 210 respondents reported animals caring and rearing problems in their area, 202 respondents reported animals’ drinking water shortage as the major issue, while 293 respondents reported about lack of timely technical information as the main constraint in carrying livestock/poultry operations.

Table 7 shows that women were having different issues in rearing their livestock/poultry. They reported that low income of the family and non-availability of timely technical knowledge which may be due to the non-availability of extension services are the major constraints they are facing. Women farmers urged for the solution of their problems. In this respect, extension workers have major responsibility of helping them and address their problems/issues to minimize the yield loss. Improper organizational structure of the extension agencies, un-understandable program objectives and lack of mobilization power of the extension staff make it difficult for the farmers to utilize their services (Shah et al., 2010; Swanson and Rajalahti, 2010; Horlings and Marsden, 2011).

Constraints faced by the respondents in farming

Farmers have always some issues in their farming whether at home or in field. Women are more likely to have more farming issues and problems as compared to men. Table 8 presents data regarding constraints faced by women in carrying out their field operations especially field activities.

Table 8 depicted that most respondents i.e. 335 were having mobility as their main constraint, followed by 300 and 295 respondents who reported that lack of timely technical information and lack of inputs were their major constraints in field operation, respectively. Similarly, 221 respondents were found having irrigation problem for their crops in their area, while 198 respondents indicated low landholding as their main problem in carrying their farming operations.

Suggestions by respondents

Table 9 contains data regarding farmer’s suggestions, out of the total 384 respondents, majority i.e. 352 of respondents suggested the need female extension staff in their respective districts, 312 respondents emphasized on subsidized inputs especially fertilizers and pesticides, 318 respondents suggested that they should be provided interest free loans, 321 respondents urged the need for female training programs, while 228 respondents stressed on the market facilities in the study area.

The suggestions of the farmers in this study were transcribed and presented in Table 9 Farmer’s vast experience of the farming practices and field

Table 7: Distribution of respondents on the basis major constraints faced in low livestock/poultry production.

|

District |

Major constraints in low livestock/poultry production |

Total |

||||

|

Cattle diseases |

Low family income |

Animals caring and rearing problems |

Drinking water shortage for animals |

Lack of timely technical information |

||

|

Bannu |

56 |

124 |

76 |

89 |

102 |

447 |

|

Swabi |

47 |

99 |

68 |

55 |

98 |

367 |

|

Swat |

62 |

77 |

66 |

58 |

93 |

356 |

|

Total |

165 |

300 |

210 |

202 |

293 |

1170 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Table 8: Distribution of respondents regarding constraints faced by them in field/farm.

|

District |

Major constraints in farming operations |

Total |

||||

|

Mobility |

Lack of inputs |

Lack of timely technical information |

Irrigation problem |

Low landholding |

||

|

Bannu |

119 |

104 |

110 |

90 |

65 |

488 |

|

Swabi |

100 |

98 |

102 |

61 |

74 |

435 |

|

Swat |

116 |

93 |

88 |

70 |

59 |

426 |

|

Total |

335 |

295 |

300 |

221 |

198 |

1349 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Table 9: Distribution of respondents on the basis of their suggestion for overall improvement.

|

District |

Suggestions of the respondents for improvement |

Total |

||||

|

Female extension staff |

Subsidized inputs |

Interest free loans |

Female trainings |

Market facilities |

||

|

Bannu |

123 |

101 |

120 |

113 |

78 |

535 |

|

Swabi |

119 |

112 |

100 |

97 |

84 |

512 |

|

Swat |

110 |

99 |

98 |

111 |

66 |

484 |

|

Total |

352 |

312 |

318 |

321 |

228 |

1531 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

operations makes them good observer of all the farming activities. The same statement was supported by the researcher herself as the researcher belongs to the same province. Therefore, farmers suggestions and recommendations should be given due importance for future improvement.

Constraints faced by women farmers in getting technical knowledge

Farmers especially women farmers faces various problems in carrying out farming practices like lack of technical assistance, costly inputs they can’t afford, irrigation water and many more (Bravo-Baumann, 2000). Data regarding various constraints faced by the women in getting technical knowledge and attending trainings were presented in Table 10. Likert scale method was applied to assess the intensity or significance of these constraints. The data exhibited that majority of the respondents in district Bannu reported Pardah as a main constraint due to which women couldn’t attend trainings or could go to extension office for assistance with highest likert scale value of 4.73, followed by language barrier (4.54) and mobility (4.51). Similalry, in Swabi, highest likert scale value (4.20) was estimated for pardah, followed by illiteracy (4.18) and mobility (3.99). Similar questions were asked from women in district Swat and their responses were recorded. In five point likert scale, mobility was ranked top with likert scale value of 4.12, followed by pardah and non-availability of information source as main constraints in getting technical information with likert scale value of 4.00 and 3.94, respectively.

Table 10: Different constraints face by women in getting technical knowledge and trainings.

|

Constraints in getting technical knowledge or trainings |

District with likert scale rank |

||

|

Bannu |

Swabi |

Swat |

|

|

Likert scale rank |

Likert scale rank |

Likert scale rank |

|

|

Pardah (Hijab) |

4.73 |

4.20 |

4.00 |

|

Mobility |

4.51 |

3.99 |

4.12 |

|

Illiteracy |

4.42 |

4.18 |

3.91 |

|

Language barrier |

3.54 |

2.89 |

3.26 |

|

Information source not availability |

4.10 |

3.76 |

3.94 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018.

Decision making

In rural areas of Pakistan, family matters are settled by men, while women mostly work as housewives. Data regarding involvement of women in decision making were collected and presented in Figure 1. The depicted data showed that majority i.e. 62.8% of the decisions are done by spouse, followed by 29.7% herself and 7.6% decision making is by anyone else that could be son, siblings or any other family elder. Women involvement in farming is very essential and their contribution should be acknowledged. These observations show resemblance with that of Pervaiz et al. (2012) who concluded that women were deprived of their due right of decision making in agriculture. In the study area women had little or no autonomy in many decision making process of the household. Women were not only dominated by their husbands but other males from the family. Similarly, Gebre et al. (2019) mentioned that regarding gender-based decision-making, 43% were male, 21% female, and 36% were joint decision-making households in their area of study. Our results are in contrast with Kalpana (2000) and Kavita (2006) who reported that majority of rural women take part in decision making. Chayal et al. (2013) argued that involvement of Indian farm women in agricultural decision-making was very limited, due to the fact that they faced male dominancy and have very little or no access to latest farm techniques.

Reasons for not involving in decision making

Table 11 shows various reasons responsible for no or less involvement of women in the decision making processes. Out of the stated reasons, male dominancy was the main reason mostly reported by majority (368) of the study respondents, followed by unskillfulness (265) and ego which was reported by (241) respondents in study area.

Table 11: Frequency distribution regarding reasons for not involving in decision making.

|

District |

Reasons for not involving in decision making |

Total |

||

|

Male dominancy |

Unskillfulness |

Ego |

||

|

Bannu |

120 |

97 |

86 |

303 |

|

Swabi |

123 |

101 |

73 |

297 |

|

Swat |

125 |

67 |

82 |

274 |

|

Total |

368 |

265 |

241 |

874 |

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018.

Note: The total may not tally due to multiple answers by the respondents.

Association of age and literacy with decision making

To investigate the association among various demographic and non-demographic attributes, Chi square statistics were applied and their results were presented in respective tables. To know the association between age and main decider regarding agriculture and livestock matters, chi square test was applied and the results are shown in Table 12. The results show a significant association between the tested variables with significance value of 0.023. It means that by increasing age of the respondents, the tendency towards involvement in decision making increases. It is common in our culture that older women are more involved in decision making of family and other farming or field operations. Same conclusions were drawn by Pervaiz et al. (2012) who stated that women in household gained more decision making power as they grow older.

Similarly, association between literacy and decision making was tested and a non-significant association was obtained which means that literacy have no effect on the decision making power of women farmers. Our results represent the same as that of Pervaiz et al. (2012) that women’s education had negative relationship with women’s decision making in household. Chayal et al. (2013) also argued that involvement of farm women in agricultural decision making is very low, they faced male dominancy and limited access to new and improved farm technology irrespective of their education.

Table 12: Association of age and literacy with main decider regarding agriculture and livestock matters.

|

Variables |

Categories |

Main decider regarding agriculture and livestock matters |

Total |

||

|

You |

Spouse |

Anyone else |

|||

|

Age |

Upto 30 years |

17(4.4) |

22(5.7) |

5(1.3) |

44 |

|

31-40 years |

12(3.1) |

113(29.4) |

14(3.6) |

139 |

|

|

41-50 |

33(8.6) |

86(22.4) |

8(2.1) |

127 |

|

|

above 50 |

52(13.5) |

20(5.2) |

2(0.5) |

74 |

|

|

Total |

114(29.7) |

241(62.8) |

29(7.6) |

384 |

|

|

x2= 5.13 P= 0.023 |

|||||

|

Literacy |

Literate |

65(19.9) |

145(37.8) |

18(4.7) |

228 |

|

Illiterate |

49(12.8) |

96(25.0) |

11(2.9) |

156 |

|

|

Total |

114(29.7) |

241(62.8) |

29(7.6) |

384 |

|

|

x2= 0.412; P= 0.814NS |

|||||

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018.

Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages. NS: Non-significant.

Association of barriers with attending trainings

Chi square test was used to know the association effect of various barriers on the probability to attend trainings or other activities and a significant association among the two variables was obtained. By analysing the chi square test, -1 correlation was observed for these two variables. It means that increasing probability of various barriers especially cultural constrains, the tendency of women farmers to attend trainings or other agricultural activities outside their homes become lower.

The test findings in Table 13 indicate that increasing the level of barriers is lowering the chances of attending agricultural trainings and other events. Therefore, it is recommended that separate female training opportunities must be provided. This could be possible by hiring local female extension officers and female field staff that will know the local traditions and customs to avoid any inconvenience to them.

Table 13: Association of barriers with attending trainings or other farming activities.

|

Barriers to attend trainings or other farming activities |

To attend trainings/other farm activities |

Total |

|

|

Yes |

No |

||

|

Male dominancy |

25(6.5) |

114(29.7) |

139 |

|

Cultural constraints |

26(6.8) |

192(50.0) |

218 |

|

Ego |

4(1.0) |

23(6.0) |

27 |

|

Total |

55(14.3) |

329(85.7) |

384 |

|

x2 =10.56, P= 0.033 |

|||

Source: Calculated by Author, 2018. Note: Values in parenthesis are percentages.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The current study inferred that in Pakistan rural women are either not taking interest or not involved in decision making process of farming and family matters. It is concluded that women are participating in all field and farm activities but their efforts are mostly unpaid. Rural women have less access to farm inputs and have less income generating opportunities as compared to men whereas they are dependent on their males for money. Majority of them are found involved in livestock and poultry related activities which are actually their domestic chores. It is concluded thatnon-availability of timely technical knowledge and extension services, low family income were the major constraints women farmers were facing. Women face various constraints in getting modern agricultural information due to male dominant society and low literacy of women. Government should establish proper mechanism for women farmers in order to facilitate them in getting technical information and performing farm operations. They may provide techniques and skill education to women in order to make them use to the latest technology in agriculture. They should be made aware of their legal rights, land ownership and access to credit facilities. Women labour work should be recognized the same as men and should be paid according to the labour law. Furthermore, they should be given easy opportunity to reproductive resources, open bank accounts and subsidized agriculture inputs like seeds, fertilizers etc. Agriculture and livestock extension services availability should be made easy to rural women. Public sector education department should strategize their policies to increase women literacy rates. Women should be empowered enough to take part in decision making process of the household that have the potential to bring about structural changes. Extension department is supposed to arrange separate female trainings/workshops and seminars for women in the selected districts.

Novelty Statement

This research focused on women farmers, their access to farming resources and role in decision making process in rural areas. Further, major constraints faced by women farmers are also reported i.e. non-availability of technical knowledge and lack of extension service in the study area.

Author’s Contribution

Mehnaz Safdar: Conducted research and wrote the manuscript as a part of PhD study.

Urooba Pervaiz: Major supervisor who developed the main idea, checked/edited the manuscript and supervised the whole research.

Dawood Jan: Helped in analysis and interpretation of data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

Akram, W., I. Naz and S. Ali. 2011. An empirical analysis of household income in rural Pakistan: Evidences from Tehsil Samundri. Pak. Econ. Soc. Rev., 49(2): 231-249.

Akter, S., P. Rutsaert, J. Luis, N.M. Htwe, S.S. San, B. Raharjo and A. Pustika. 2017. Women’s empowerment and gender equity in agriculture: A different perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy. 69: 270-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2017.05.003

Amin, H., T. Ali, M. Ahmad, and M.I. Zafar. 2009. Participation level of rural women in agricultural activities. Pak. J. Agric. Sci., 46(4): 30-42.

Anaglo, N.J., S.D. Boateng and C.A. Boateng. 2014. Gender and access to agricultural resources by small holder farmers in the Upper West Region of Ghana. J. Educ. Pract., 5(5): 17-22.

Anderson, C.L., T.W. Reynolds and M.K. Gugerty. 2017. Husband and wife perspectives on farm household decision-making authority and evidence on intra-household accord in rural Tanzania. World Dev., 90: 169-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.09.005

Badiger, P.L. and H.P. Huilgal. 2004. Participation of farm women in agriculture and animal husbandry. Indian Res. J. Ext. Educ., 4(1 and 2): 124.

Bala, N. 2010. Selective discrimination against women in Indian Agriculture. A review. Agric. Rev., 31(3): 224-228.

Bravo-Baumann, H. 2000. Gender and livestock. capitalisation of experiences on livestock

projects and gender. Working document. Swiss Development Cooperation, Bern.

Butt, M.T., Z.Y. Hassan, K. Mehmood and S. Muhammad. 2010. Role of rural women in agricultural development and their constraints. J. Agric. Soc. Sci., 6(3): 24-29.

Chayal, K., B.L. Dhaka, M.K. Poonia, S.V.S. Tyagi and S.R. Verma. 2013. Involvement of Farm Women in Decision-making in Agriculture. Stud. Home Commun. Sci., 7(1): 35-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/09737189.2013.11885390

Damisa, R. Samndi and M. Yohana. 2007. Women participation in agricultural production. A probit analysis. J. Appl. Sci., 7(3): 412-416. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2007.412.416

Deere, C.D. and C.R. Doss. 2006. Gender and the distribution of wealth in developing countries. UNU-WIDER Research Paper No. 2006/115. Helsinki. pp. 23-25.

Dillon, A. and E. Quinones. 2010. Gender- differentiated asset dynamics in Northern Nigeria. Background paper prepared for The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–11. Rome: FAO. pp. 14-17.

FAO. 2010. The State of Food and Agriculture- Women in agriculture closing the gender gap for development. Rome.

Farid, 2009. Nature and extent of rural women’s participation in agricultural and non-agricultural activities. Agric. Sci. Digest., 29(4): 254-259.

Gebre, G.G., H. Isoda, Y. Amekawa and H. Nomura. 2019. Gender differences in the adoption of agricultural technology: The case of improved maize varieties in southern Ethiopia. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum, 76: 102264-102270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2019.102264

Guèye, E.F. 2000. The role of family poultry in poverty alleviation, food security and the promotion of gender equality in rural Africa. Outlook Agric., 29(2): 129-136. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000000101293130

Horlings, L.G. and T.K. Marsden. 2011. Towards the real green revolution. Exploring the conceptual dimensions of a new ecological modernization of agriculture that could feed the world. Glob. Environ. Change, 21(1): 441-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.004

Jamali, K. 2009. The role of rural women in agriculture and its allied fields: A case study of Pakistan. Eur. J. Soc. Sci., 7(3): 74-75.

Kalpana, M. 2000. Role of women in farm and home decision. M.Sc. (Agri.) thesis (Unpub.), Dr. Punjabrao Deshmukh Krishi Vidya peeth, Akola (M.S.).

Kavita, R. 2006. A study on the women participation of farm operations and decision making in agriculture. Ext. Educ. Manage., 15(4): 26-30.

Khan, A., S. Sanaullah, S.A. Ali, S.A. Shah and S.U. Khan. 2019. Determinants of farmers’ perception about climate change in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa-Pakistan. Pure Appl. Biol., 8(4): 2159-2168. https://doi.org/10.19045/bspab.2019.80161

Lal, R. and A. Khurana. 2011. Gender issues: The role of women in agriculture sector. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manage. Res., 1(1): 29-39.

Mugede, S.M., 2013. The role of rural women in agriculture. http://www.wfooma.org/women-in-agriculture/articles/the-role-of-rural women-inagriculture.html.

Nazly, Y., A. Shafique, S. Salim and A.A. Maan. 2004. Awareness among working women about their exploitation in home based industry of Faisalabad, Pakistan. Int. J. Agric. Biol., 6(3): 53-59.

Patil, B. and V.S. Babus. 2018. Role of women in agriculture. Int. J. Appl. Res., 4(12): 109-114.

Pervaiz, U., D. Jan, M.Z. Khan and A. Khan. 2012. Women in agricultural decision making: Pakistan’s experience. Sarhad J. Agric., 28(2): 361-364.

Praveena, V. 2005. Decision making pattern of rural women in farm related activities. Agric. Ext. Rev., 3: 3-7.

Quisumbing, A.R. and L. Pandolfelli. 2010. Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers: resources, constraints, and interventions. World Dev., 38: 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.10.006

Sabarathnam, V.E. 1988. Manual on field experience training for ARS Scientists, National Academy and Agricultural Research Management (NAARM), Hyderabad.

Sadaf, S., A. Javed and M. Luqman. 2006. Preferences of rural women for agricultural information sources: a case study of District Faisalabad-Pakistan. J. Agric. Soc. Sci., 2(3): 145-149.

Sanaullah and U. Pervaiz. 2019. An effectiveness of extension trainings on boosting agriculture in Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) of Pakistan: An evidence from Bajaur Agency. Sarhad J. Agric., 35(3): 890-895. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2019/35.3.890.895

Sanaullah, U. Pervaiz, S. Ali, M. Fayaz and A. Khan. 2020. The impact of improved farming practices on maize yield in federally administered tribal areas, Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 36(1): 34-43. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2020/36.1.348.358

Santra, S.K. and R. Kundu. 2001. Women’s empowerment for sustainable agriculture development. Manage. Ext. Res. Rev. India, 20(2): 131–146.

Shah, M.T.A., M. Israr, N. Khan, N. Ahmad, M.M. Shafi and S. Raza. 2010. Agriculture extension curriculum: An analysis of agriculture extension students views in the agricultural universities of Pakistan. Sarhad J. Agric., 26(3): 435-442.

Sharma, A., D. Singh and G.S. Solanki. 2014. Role of farm women in agricultural operations and decision making pattern. Indian Res. J. Ext. Educ., 14(2): 1-3.

Singh, D. and D. Vinay. 2013. Gender participation in Indian agriculture: An ergonomic evaluation of occupational hazard of farm and allied activities. Int. J. Agric. Environ. Biotechnol., 6(1): 157-168.

Steinzor, N. 2003. Women’s property and inheritance rights: improving lives in a changing time. Final synthesis and conference proceedings paper. USAID and WID tech. pp. 45-56.

Swanson, B.E. and R. Rajalahti. 2010. Strengthening agricultural extension and advisory systems: procedures for assessing, transforming and evaluating extension systems. The World Bank, Washington DC, USA. pp. 18-21.

Tangka, F.K., M.A. Jabbar and B.I. Shapiro. 2000. Gender roles and child nutrition in livestock production systems in developing countries: A critical review. Socio-economics and Policy Research Working Paper 27. International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya.

Thornton, P.K., R.L. Kruska, N. Henninger, P.M. Kristjanson, R.S. Reid, F. Atieno, A.N. Odero and T. Ndegwa. 2002. Mapping poverty and livestock in the developing world. International Livestock Research Institute, Nairobi, Kenya. pp. 124.

Tung, D.X. 2005. Smallholder poultry production in vietnam: Marketing characteristics and strategies. Paper presented at the workshop Does Poultry Reduce Poverty? A Need for Rethinking the Approaches, 30-31 August. Copenhagen, Network for Smallholder Poultry Development.

World Bank. 2008. Gender and agriculture source book, Washington, DC. pp. 234-246.

Yahaya, K.M. 2001. Media pattern of women farmers in Northern Nigeria: imperatives for sustainable and gender sensitive extension delivery. Afr. Crop Sci. Conf. Proc., 5(1): 747-754.

Zaheer, R., A. Zeb and S.W. Khattak. 2014. Women participation in agriculture in Pakistan: An overview of the constraint and problems faced by rural women. J. Bus. Manage., 16(2): 1-04. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-16220104

Zia, Q. 2000. Role of rural skilled and unskilled factory working women in the rural economy. Unpublished M.Sc (Hons) thesis, Rural Sociology Department University of Agriculture Faisalabad. pp. 35-39.

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?

..... (2)

..... (2)