Factors Influencing IFMC Farmer’s Attitude towards Government Extension Services in Bangladesh

Research Article

1Md. Faruq Hasan, 2Nazmunnahar Kolpona, 3*Atia Shahin, 3Md. Rayhan Sojib and 3Susmita Sarmin

1Professor, Department of Agricultural Extension, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh; 2Former MS Fellow, Department of Agricultural Extension, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh; 3Lecturer, Department of Agricultural Extension, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh.

Abstract | The Integrated Farm Management Component (IFMC) programme under the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) aimed to enhance agricultural productivity among landless, marginal, and small farming households primarily by promoting agricultural growth and employment and enhancing the credibility of government extension services. The objective of this study was to determine the attitude of IFMC-beneficiary farmers towards government extension services as well as identify the socioeconomic factors influencing these farmers’ attitude towards the services provided by the government. The attitude statements were constructed using Thurston’s equal-appearing interval technique. Sixteen statements were used to assess the attitude of the farmers using a Likert scale. One hundred twenty-five (125) IFMC farmers from Phulbari upazila in Dinajpur district receiving government extension services were selected for data collection using a multi-stage random sampling procedure. The percentages, means, and standard deviations were employed to summarise the data gathered during the interviews. The inferential statistical investigation involved using correlation analysis and multiple regression analysis. The findings revealed that a significant proportion (72.8 percent) of the respondents held a moderately to highly unfavourable attitude towards government extension services. The key factors influencing farmers’ attitude were individual extension contact, training experience, educational qualification, farm size, annual income, and mass media contact, respectively. Thus, to enhance farmer engagement and trust in government extension services, policy formulation should be aimed at proactive and collaborative communication, emphasising tailored solutions, building a strong extension network, maintaining transparency, arranging digital platforms, targeted awareness campaigns, and practical training.

Received | January 17, 2024; Accepted | July 11, 2024; Published | October 04, 2024

*Correspondence | Atia Shahin, Lecturer, Department of Agricultural Extension, Hajee Mohammad Danesh Science and Technology University, Dinajpur, Bangladesh; Email: atia.hstu@gmail.com

Citation | Hasan, M.F, N. Kolpona., A. Shahin., M.R. Sojib. and S. Sarmin. 2024. Factors influencing IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services in Bangladesh. Sarhad Journal of Agriculture, 40(4): 1181-1195.

DOI | https://dx.doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2024/40.4.1181.1195

Keywords | Attitude, DAE, IFMC farmer, Government extension services, Likert scale

Copyright: 2024 by the authors. Licensee ResearchersLinks Ltd, England, UK.

This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Bangladesh is widely regarded as one of the less developed countries globally, with a population of 165 million, making it one of the most densely populated nations (BBS, 2022). Agriculture is widely recognized as the backbone of Bangladesh’s economy, as it constitutes the dominant economic activity and is considered crucial to the country’s well-being (Pawlak and Kołodziejczak, 2020). As the leading private enterprise in Bangladesh, the agricultural sector encompasses crops, livestock, fisheries, and forestry, makes up approximately 11 percent of the country’s GDP, and supports the livelihoods of around 45 percent of the workforce (Bangladesh Economic Review, 2023). In light of its pivotal role in generating employment opportunities and alleviating poverty, this sector’s impact on the national income continues to be significant, despite its comparatively modest contribution (Uddin et al., 2016).

The advancement of agriculture is profoundly dependent on the delivery of high-quality extension services (Agholor et al., 2013). Agricultural extension services emerged on a global scale as an institutional mechanism aimed at promoting rural development and modernising agriculture (Baiyegunhi et al., 2019). Extension services offer farmers relevant and up-to-date information to help them solve farming-related issues and make better agricultural decisions (Moyo and Salawu, 2018). The government of Bangladesh places significant emphasis on agricultural development through agricultural extension services delivered to farmer’s doorsteps, which are operationalized by various public sector organisations. The Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE), a pivotal agency operating within the Ministry of Agriculture, performs a critical function in enhancing the standard of living of agricultural communities (Kabir and Islam, 2023). The DAE encourages and supports the grassroots planning and execution of all agricultural extension activities and provides unified extension services to farmers nationwide (Uddin et al., 2016). The DAE also collaborates with government organisations, non-government organisations, and the private sector to achieve its objectives (Chowdhury et al., 2014). One such programme was the Integrated Farm Management Component (IFMC), which aimed to improve the sustainability, profitability, and productivity of farming systems by integrating and optimising resource utilisation and integrating the most advanced agricultural technologies and practices (Nordic Consulting Group, n.d.).

The IFMC was the largest component of the Agricultural Growth and Employment Programme (AGEP), funded by Danida for the development of the agricultural sector in Bangladesh. The IFMC programme was implemented by the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) under the Ministry of Agriculture, Bangladesh. It promoted the concept of Integrated Farm Management through Farmer’s Field Schools (FFSs), along with considering the objective of increased agricultural production and diversification among female and male members of landless, marginal, and small farming households. About 1 million female and male farmers from 373 upazilas of 61 districts have participated in 20,000 FFSs under this program (AGEP, 2013). It is needless to say that the farmers who tirelessly toil in the fields are the true heroes of the nation, having successfully achieved self-sufficiency in food for the growing population using ever-diminishing agricultural land (Hossain, 2017). Farmers must be informed about technologies to improve agricultural productivity (Takahashi et al., 2020). The IFMC initiated comprehensive initiatives aimed at educating and training farmers on cutting-edge agricultural methodologies, innovative instruments, and sustainable approaches to maximise yields and optimise resource utilisation (NCG, n.d.).

The collaboration of extension personnel as professional leaders and farmers is crucial for the effective dissemination of innovation. At this time, the research and extension delivery system are devoting significant resources to bolster agricultural output within the nation. Nevertheless, the precise surge in output will be contingent upon the farmer’s receptiveness to the extension services rendered by governmental organisations. This is because the farmer’s attitude plays a pivotal role in facilitating the diffusion of innovations and the process of adaptation (Biswas et al., 2021). Considering the substantial influence that farmer’s attitudes exert on the dissemination of innovations and practices, the manner in which farmers perceive extension services is a vital element in ensuring the efficient spread of agricultural innovations (Robi et al., 2023).

Several studies have been conducted on farmer’s attitudes towards extension services in different parts of the world (Rebecca, 2012; Kaur et al., 2014; Sebeho,

2016; Pandey et al., 2020; Onyemekihia et al., 2021; Masanja et al., 2023). Nonetheless, relatively little research has been carried out in Bangladesh on farmer’s attitude towards extension services, e.g., Arifullah et al., 2014; Das et al., 2021. None of the research was conducted on IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services in Bangladesh. Considering these facts and their practical usefulness, the present study was undertaken to determine the attitude of IFMC-beneficiary farmers towards government extension services and to identify the socioeconomic factors influencing these farmer’s attitude towards government extension services.

Materials and Methods

In conducting this study, an explanatory cross-sectional research design was employed. The methodology is further expanded in the subsequent subsections:

Study area

The study was carried out in the Phulbari upazila (administrative unit) of Dinajpur district in the northern part of Bangladesh. This is where the IFMC programme administered by the Department of Agricultural Extension is most prominent. The upazila is covered by three Agro-ecological zones. These were AEZ 3 (Tista Meander Floodplain), AEZ 25 (Level Barind Tract), and AEZ 27 (North-Eastern Barind Tract). Phulbari upazila is at 25.50° North latitude and 88.95° East longitude, and it covers an area of about 228.49 square kilometres. In the upazila, 52.6 percent of people are literate, with men of being 54.6 percent and 50.5 women of being percent, and 68.83 percent of the people in the upazila make their living from farming, and the main crops they grow are rice, wheat, jute, sugarcane, potatoes, pulses, oil seeds, and vegetables (Banglapedia, n.d.). The maps of the study area have been presented in Figure 1.

Sampling design

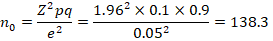

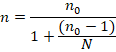

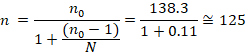

For this study, we employed a multi-stage random selection technique. Out of seven unions in Phulbari upazila, four were selected for data collection. An updated list of all the farmers participating in the IFMC program in these four unions was collected from the Upazila Agriculture Office. There were 1206 enlisted farmers receiving agricultural extension services under the IFMC program, which constituted the population of the study. To pick a sample of farmers, Cochran’s (1977) sample size calculating formula was used. The Cochran formula is:

Where, no is Cochran’s sample size recommendation.

For this study,

Confidence level = 95%

e (the margin of error) = 5%

p (proportion of the population) = 10%

q = (1 - p) = (1 - 0.1) = 0.9

The Z-value for 95% confidence level is 1.96

Thus,

Thus, the sample size for this study is:

Here, n is the new adjusted sample size.

N is the population size, and here it is 1206.

So, the sample size is 125. In addition, a reserve list containing 10 percent of the sample (13 farmers) was made to use in case the original sampled farmers were unavailable for interview. The detailed distribution of the population and sample is shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Distribution of the population and sample.

|

Unions |

Population |

Sample farmers |

Reserve list |

|

Aladipur |

270 |

27 |

3 |

|

Eluary |

393 |

40 |

4 |

|

Betdighi |

331 |

35 |

4 |

|

Khayerbari |

212 |

23 |

2 |

|

Total= |

1206 |

125 |

13 |

Research instrument and data collection

For the purpose of collecting data, an interview schedule was utilised. Both open and closed form questions and scales were used in the interview schedule according to the need. The interview schedule focused on assembling data on different profile characteristics of the IFMC farmers. In addition, the inclination or feeling of the farmers towards agricultural extension services provided by the DAE was determined to capture their attitude towards government extension services. The interview schedule was pretested with 24 farmers (other than the sample farmers) in the study area. Prior to completing the interview schedule, required adjustments and amendments were made based on the pre-test. The interviews were individually conducted with the respondents at their respective residences from September 2019 to February 2020.

Measurement of independent variables

Twelve variables were evaluated to describe the profile characteristics of the sample farmers. The measuring techniques and probable scales for these properties are shown in Table 2.

Measurement of the dependent variable

The dependent variable of the study was IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services. The variable was measured through a Likert scale (Likert, 1932). The scale was constructed by following the ‘equal-appearing interval’ scaling technique, which was developed by Thurstone and Chave (1929). In this study, attitude was operationalized as the mental predisposition of the farmers to the extent of knowledge, belief, and action tendency towards government extension services in varying degrees of favourableness or unavoidableness. Possible statements concerning the government extension services with respect to information dissemination, information service, skill development, credibility of information and services, etc., were collected based on a review of the literature. Primarily, a total of 42 statements were constructed to be used in the construction of the attitude scale and then screened following the criteria suggested by Edwards (1957). Based on the screening, a total of 28 statements were selected for judge’s ratings by 30 judges selected from different related disciplines. The judge rating assesses the appropriateness of the statements regarding the farmer’s attitude towards government extension services using a 9-point continuum scale. There were a total of 24

Table 2: Measurement techniques for different independent variables.

|

Scoring method |

Scale/Score |

|

|

Age |

Number of years since the birth |

- |

|

Educational qualification |

Year of schooling |

1 = Each year of completion, 0.5 = Can sign name only, 0 = Cannot read and write |

|

Family size |

Number of members in the family |

- |

|

Farm size |

Hectare |

- |

|

Farming experience |

Number of years |

- |

|

Training experience |

Number of days |

- |

|

Annual income |

Thousand BDT* |

- |

|

Organisational participation |

The score calculated by multiplying the extent of participation by the duration of participation |

Score |

|

Agricultural knowledge |

Twenty-four questions of different weights regarding different aspects of agriculture were generated following Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom, 1956) |

Score |

|

Individual extension contact |

The score was computed based on a respondent’s extent of contact with 15 selected individual extension sources |

Frequently = 3, Occasionally = 2, Rarely = 1, Not at all= 0 |

|

Group extension contact |

The score was computed based on a respondent’s extent of contact with 15 selected group extension sources |

Frequently = 3, Occasionally = 2, Rarely = 1, Not at all = 0 |

|

Mass extension contact |

The score was computed based on a respondent’s extent of contact with 15 selected mass extension sources |

Frequently = 3, Occasionally = 2, Rarely = 1, Not at all = 0 |

* Thousand BDT = Approximately $9.04

judges who responded. The scale values and Q values were calculated for the 28 statements in accordance with the methodology proposed by Edwards (1969).

Computation of scale values

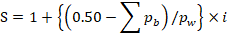

The scale values (S) for 28 attitude statements were determined by computing the medians of the ratings given by 24 judges who rated the statements using equal-appearing intervals. Statements with low S values were rejected for inclusion in the scale.

Where, S= the median or scale value of the statement, l= the lower limit of the interval in which the median falls, Σpb=sum of proportions below median interval, pw=proportion within the median interval, and i=the width of the interval (1.0).

Calculation of Q values

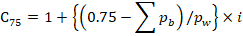

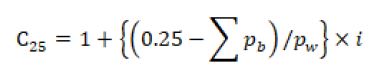

Since relying solely on the median value for the scale value does not ensure an equal appearing interval, it is necessary to account for ambiguity, uncertainty, or disagreement among the judges regarding the ordering of each statement (Edwards, 1969). The interquartile range (Q), which served as a measure of dispersion for the statements on the scale, was utilised to accomplish this. The statements that possessed high Q values were omitted from the scale. The interquartile range comprises the central 50% of judgements regarding a given statement, serving as an indicator of the variability in the judgement distribution. For the purpose of calculating Q, the 75th and 25th centiles must be acquired.

Where, C75 = 75th centile, l= the lower limit of the interval in which the 75th centile falls, Σpb=the sum of the proportions below 75th centile interval, pw =the proportion within the 75th centile interval, i=the width of the interval (1.0).

Table 3: Computation of equal-appearing intervals (S-values and Q-values of 28 Statements), statement analysis and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α)

|

Statement number |

S values |

Q values |

Decision to put in pre-test |

t values |

Decision to put in final scale |

Cronbach’s α if item deleted |

|

1 (+) |

5.25 |

3.14 |

Yes |

5.814 |

Yes |

0.933 |

|

2 (-) |

8.50 |

6.08 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

3 (-) |

8.00 |

2.00 |

Yes |

4.602 |

Yes |

0.943 |

|

4 (+) |

8.50 |

3.30 |

Yes |

1.597 |

No |

- |

|

5 (-) |

7.50 |

4.00 |

Yes |

3.841 |

Yes |

0.943 |

|

6 (-) |

4.83 |

4.67 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

7 (+) |

6.00 |

4.00 |

Yes |

4.919 |

Yes |

0.935 |

|

8 (-) |

5.17 |

2.50 |

Yes |

3.402 |

Yes |

0.948 |

|

9 (+) |

8.00 |

3.00 |

Yes |

1.431 |

No |

- |

|

10 (-) |

9.50 |

4.83 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

11 (-) |

6.50 |

1.40 |

Yes |

4.602 |

Yes |

0.937 |

|

12 (+) |

7.50 |

2.67 |

Yes |

1.597 |

No |

- |

|

13 (-) |

6.17 |

1.67 |

Yes |

3.841 |

Yes |

0.943 |

|

14 (-) |

4.00 |

5.00 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

15 (+) |

7.70 |

2.40 |

Yes |

4.919 |

Yes |

0.935 |

|

16 (+) |

5.50 |

3.67 |

Yes |

3.402 |

Yes |

0.935 |

|

17 (-) |

8.00 |

1.33 |

Yes |

5.534 |

Yes |

0.943 |

|

18 (+) |

9.00 |

3.67 |

Yes |

4.385 |

Yes |

0.938 |

|

19 (+) |

6.00 |

2.50 |

Yes |

1.348 |

No |

- |

|

20 (+) |

9.00 |

3.75 |

Yes |

5.394 |

Yes |

0.944 |

|

21 (-) |

7.50 |

2.00 |

Yes |

1.597 |

No |

- |

|

22 (-) |

6.50 |

4.00 |

Yes |

3.503 |

Yes |

0.943 |

|

23 (-) |

6.00 |

3.83 |

Yes |

4.392 |

Yes |

0.948 |

|

24 (+) |

5.50 |

2.00 |

Yes |

4.385 |

Yes |

0.935 |

|

25 (+) |

8.50 |

6.00 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

26 (-) |

4.50 |

2.00 |

No |

- |

- |

- |

|

27 (+) |

5.50 |

3.67 |

Yes |

1.319 |

No |

- |

|

28 (+) |

9.50 |

3.25 |

Yes |

2.445 |

Yes |

0.935 |

Where, C25 = 25th centile, l= the lower limit of 25th centile interval, Σpb =the sum of the proportions below 25th centile interval, pw =the proportion within 25th centile interval, i=the width of the interval (1.0). The computed scale (S) and interquartile range (Q) values are tabulated in Table 3.

Selection of attitude statements based on S and Q-values

The primary indication that a statement was ambiguous, according to Thurstone and Chave, (1929), were a low scale value (S) and a high Q-value. Twenty-two statements, whose Q-values varied from 1.33 to 4.00 and whose scale values spanned from 4.50 to 9.50, were included in the current study in accordance with the mentioned criteria. Statements with a Q-value of less than 4.57 (mean + standard deviation = 3.30 + 1.27), and a scale value greater than 5.32 (range greater than 6.91 – 1.59), were chosen based on the evaluations of the judges.

Statement analysis using Likert’s summated rating method

For the final scale selection, 22 statements were selected based on scale values and Q-values and evaluated using Likert’s Summated Ratings Technique. The claims were evaluated using pre-test data provided from 24 farmers. The farmers, who were administered the statements were chosen at random and did not correspond to the sample farmers in the current study, but they were representative of the research population. Statement analysis consisted of calculating the frequency distribution of scores based on pretest responses to all statements. The top 25% of respondents with the highest scores (high group) and the bottom 25% of respondents with the lowest scores (low group) served as criterion groups for evaluating individual claims. The crucial ratio (t-value) was computed using the following formula proposed by Edwards (1957). The value of ‘t’ represented the degree to which a particular statement distinguished between the high and low categories. Edwards (1957) recommended discarding items with ‘t’ values < 1.75. The attitude towards government extension services scale was validated by selecting statements with ‘t’ values > 1.75, ensuring its content validity.

Internal reliability by Cronbach’s alpha

The scale item’s internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. It was discovered that the 16 statement’s Cronbach’s alpha was 0.951, which was higher than 0.9. Excellent reliability is indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha value of > 0.9 (George and Mallery, 2003). Nevertheless, eliminating any of the factors has no effect on raising or increasing the Cronbach’s alpha value from 0.951. As a result, it may be concluded that the assertions of internal consistency or reliability were sufficient. It indicates that the scale created by the aforementioned methods was trustworthy.

Owing to this, 16 statements, comprising 8 positive and 8 negative statements, were included in the final attitude scale regarding government extension services (Table 3). For the purpose of allowing for genuine emotions free from bias, these chosen statements were positioned in the scale at random. A final scale was employed with the following response options: ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘undecided’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree’ with corresponding scores of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, and the negative statements were given a reverse score. Hence, the cumulative attitude score of a farmer could range from 16 to 80; where 16 indicates a highly unfavourable attitude and 80 indicates a highly favourable attitude towards government extension services. Besides this, Attitude Index (AI) and Rank Order (RO) were also calculated. The Attitude Index (Al) was utilised to signify the scores of specific assertions, which were calculated by adding together all of the responses (Hasan et al., 2019, Hasan et al., 2020). The AI scores for each of the 16 statements were distributed as Rank Order (RO) 1 through 16, starting with the highest scores and working their way down. The AI was computed using the following formula:

Attitude Index (AI) for positive statements = NSA×5 + NA×4 + NU×3 + ND×2 + NSD×1

Attitude Index (AI) for negative statements = NSA×1 + NA×2 + NU×3 + ND×4 + NSD×5

Where, NSA= Number of farmers responding ‘strongly agree’, NA= Number of farmers responding ‘agree’, NU= Number of farmers responding ‘undecided’, ND= Number of farmers responding ‘disagree’, NSD= Number of farmers responding ‘strongly disagree’

Data analysis

Various descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and inferential statistics such as correlation and multiple linear regression (enter and stepwise method) were employed in this study. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to manage multicollinearity. Overall, version 25 of the Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences (SPSS) programme was used to analyse the data.

Results

IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services

IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services was the dependent variable of the study. The attitude score varied from 18 to 79, against a possible range of 16 to 80. The mean score of farmer’s attitude towards government extension services was 44.82 with a standard deviation of 11.75. The respondents were divided into five categories, as shown in Table 4, using equal distributions of the possible range of attitude score.

Table 4: Distribution of the IFMC farmers according to their attitude score.

|

Categories |

Respondents (n=125) |

Mean |

SD |

|

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|||

|

Highly unfavourable (16–31) |

20 |

16.0 |

44.82 |

11.75 |

|

Moderately unfavourable (32-47) |

71 |

56.8 |

||

|

Neutral (48) |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Moderately favourable (49-64) |

28 |

22.4 |

||

|

Highly favourable (65-80) |

6 |

4.8 |

||

|

Total |

125 |

100.0 |

||

SD= Standard deviation

Table 5: The ranking of statements regarding the attitude of farmers.

|

Sl. No. |

Statements |

Score (AI) |

Rank (RO) |

|

1 (+) |

Participation in government agricultural training programs is effective to produce more qualitative products |

294 |

10 |

|

2 (-) |

I feel family restriction to participate in agricultural meetings arranged by SAAO or AEO |

286 |

14 |

|

3 (+) |

Communication with the government extension personnel (like SAAO, AEO) for sharing agricultural information will improve our agricultural knowledge |

359 |

8 |

|

4 (-) |

The agricultural technologies/information provided by DAE are not appropriate for all kinds of farmers |

291 |

11 |

|

5 (+) |

Extension agents of DAE have sufficient quality to provide extension services |

402 |

6 |

|

6 (-) |

DAE is not impartial to farmer selection for their extension activities |

288 |

13 |

|

7 (+) |

I feel proud to participate in the agricultural extension activities of DAE |

444 |

4 |

|

8(-) |

Resource poor farmers are not allowed to take training of agricultural activities from DAE |

467 |

2 |

|

9(+) |

SAAO can motivate farmers to adopt new technologies |

330 |

9 |

|

10(-) |

Extension services of DAE are not credible for agricultural information |

248 |

16 |

|

11(+) |

SAAO’s guidance can be obtained when there is an urgent need for information |

363 |

7 |

|

12(-) |

Government extension service’s current infrastructure and accommodations are insufficient to satisfy farmer’s information requirements |

289 |

12 |

|

13(+) |

Government extension can successfully demonstrate improved technologies to farmers |

406 |

5 |

|

14(-) |

Year after year, SAAO’s extension services appear to remain consistent |

285 |

15 |

|

15(+) |

Extension services provided by SAAO are reliable, practical and for solving farmer’s problems |

448 |

3 |

|

16(-) |

Government extension services cannot provide all possible solutions to the farmer’s problems |

468 |

1 |

AI=Attitude Index, RO=Rank Order

The findings implied that around three quarters (72.8 percent) of the respondents were clustered around the moderately to highly unfavourable attitude towards government extension services category. A little more than a quarter (27.2 percent) of the respondents had a favourable (moderate to high) attitude towards government extension services; however, none had a neutral attitude.

The farmer’s attitude statements were evaluated by calculating their total score and ranking them. Table 5, corresponds to each statement used to measure IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services.

The statements with the highest agreement level were, “Government extension services cannot provide all possible solutions to the farmer’s problems”, “Resource poor farmers are not allowed to take training of agricultural activities from DAE” and “Extension services provided by SAAO are reliable, practical and for solving farmer’s problems”. Conversely, there was a contradiction with the statement, “Extension services of DAE are not credible for agricultural information”. Similarly, farmers disagreed with the statement, “Year after year, SAAO’s extension services appear to remain consistent”.

Socio-economic demographics of the IFMC farmers

The findings of the twelve (12) selected characteristics of the farmers are presented in Table 6. The respondents were classified in suitable categories for describing their selected characteristics.

The findings implied that the overwhelming majority of the farmers in the study area were young to middle aged (95.2 percent), and the majority could sign their name only. Around 40 percent of the respondents had an education of primary to secondary level. Majority of the farmers had small to medium sized families (88.8 percent) and possessed small sized farms. The farmers had 1 to 2 decades of farming experience and had an experience of above daylong training. An overwhelming majority of the farmers had medium

Table 6: Distribution of the IFMC farmers based on their selected characteristics scores (n =125).

|

Characteristics |

Observed range |

Categories |

Respondents (Percentage) |

Mean |

SD |

|||

|

Age |

22-59 |

Young (≤ 35) |

32.8 |

39.80 |

9.32 |

|||

|

Middle (36-55) |

62.4 |

|||||||

|

Old (> 55) |

4.8 |

|||||||

|

Educational qualification |

0.5-12 |

Can sign name only (0.5) |

51.2 |

4.02 |

4.19 |

|||

|

Primary (1-5) |

14.4 |

|||||||

|

Secondary (6-10) |

24.8 |

|||||||

|

Above secondary (11-12) |

9.6 |

|||||||

|

Family size |

3-8 |

Small (1-4) |

47.2 |

4.78 |

1.24 |

|||

|

Medium (5-6) |

41.6 |

|||||||

|

Large (>6) |

11.2 |

|||||||

|

Farm size |

0.210-3.987 |

Small (0.21-1.0) |

61.6 |

0.59 |

0.65 |

|||

|

Medium (1.01-3.0) |

37.6 |

|||||||

|

Large (>3) |

0.8 |

|||||||

|

Farming experience |

1-33 |

One decade (1-10) |

33.6 |

15.39 |

8.42 |

|||

|

Two decades (11-20) |

46.4 |

|||||||

|

Above two decades (>20) |

20.0 |

|||||||

|

Training experience |

0-7 |

No (0) |

12.8 |

2.70 |

2.42 |

|||

|

Daylong (1) |

32.8 |

|||||||

|

Above daylong (>1) |

54.4 |

|||||||

|

Annual income |

90-493 |

Low (≤ 100.00) |

9.6 |

170.41 |

64.32 |

|||

|

Medium (100.01-200.00) |

87.2 |

|||||||

|

High (>200.00) |

3.2 |

|||||||

|

Organisational participation |

1-9 |

Low (≤ 3) |

40.8 |

|||||

|

Medium (4-6) |

42.4 |

4.17 |

2.29 |

|||||

|

High (>6) |

16.8 |

|||||||

|

Agricultural knowledge |

19-85 |

Fair (≤ 30) |

14.4 |

60.26 |

18.37 |

|||

|

Good (31-60) |

43.2 |

|||||||

|

Excellent (>60) |

42.4 |

|||||||

|

Individual extension contact |

1-15 |

Low (≤ 5) |

44.0 |

|||||

|

Medium (6-10) |

36.0 |

7.42 |

3.05 |

|||||

|

High (above 10) |

20.0 |

|||||||

|

Group extension contact |

1-9 |

Low (≤ 3) |

24.8 |

|||||

|

Medium (4-6) |

56.0 |

4.57 |

1.94 |

|||||

|

High (>6) |

19.2 |

|||||||

|

Mass extension contact |

1-9 |

Low (≤ 3) |

51.2 |

|||||

|

Medium (4-6) |

37.6 |

3.92 |

1.83 |

|||||

|

High (>6) |

11.2 |

|||||||

SD = Standard Deviation

annual income while they had low to medium participation in different organisations. On the other hand, they had good to excellent knowledge in different agricultural issues. In terms of contact with different extension media, majority had low contact with individual (Upazila Agriculture Officer, Agricultural Extension Officer, Sub-Assistant Agriculture Officer, etc.) and mass media (Radio-Television programs, Newspaper, etc.) while medium contact with different group media (Group discussion, result and method demonstration, etc.).

Factors influencing IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services

Three steps were followed to determine the influence of different factors on farmer’s attitude towards government extension services: first, the correlation analysis; second, the multiple linear regression; and finally, the stepwise multiple regression. The steps are given in the following subsections:

Result of correlation analysis: The correlation analysis (Table 7) shows that eight out of twelve variables are significantly related to the farmer’s attitude towards government extension services. Among the eight significant independent variables, seven, namely, educational qualification, farm size, training experience, organisational participation, agricultural knowledge, individual extension contact and mass extension contact had a significant positive relationship. In contrast, annual income had a significant negative relationship with the dependent variable.

Table 7: Correlation coefficients of the selected characteristics of the farmers and their attitude towards government extension services.

|

Selected characteristics |

Correlation coefficients with attitude towards government extension services (123 d.f.) |

|

Age |

-0.017 |

|

Educational qualification |

0.503** |

|

Family size |

-0.044 |

|

Farm size |

0.516** |

|

Farming experience |

0.038 |

|

Training experience |

0.629** |

|

Annual income |

-0.299* |

|

Organisational participation |

0.253** |

|

Agricultural knowledge |

0.289** |

|

Individual extension contact |

0.676** |

|

Group extension contact |

0.068 |

|

Mass extension contact |

0.270* |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level and ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level.

Result of multiple regression analysis: Multiple regression analysis (both enter and stepwise methods) was run to determine the influence of explanatory variables on farmer’s attitude. Out of twelve independent variables, eight were included in regression analysis due to their significant values in correlation analysis (Table 8). The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was utilised to assess the presence of multicollinearity among the variables. The maximum VIF value was 2.155, the variables had high tolerance values as well, so multicollinearity was not a concern.

The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates that all the independent variables explain 81.7 percent of the variance in farmer’s attitude. The adjusted R2, calculated by only including the significant independent variables, reveals that 80.4 percent of the dependent variable’s variation is attributable to these independent variables. The F-test result of 64.67 is significant at p<0.01, indicating that the multiple regression model significantly influences the dependent variable in this investigation. Hence, this model is a perfect fit to predict the significant contributions of independent variables.

The observed t-value for the regression coefficient was significant for six variables (Table 8) namely: educational qualification (X1), farm size (X2), training experience (X3), annual income (X4), individual extension contact (X7) and mass extension contact (X8). Among these variables, educational qualification (X1), farm size (X2), training experience (X3), and individual extension contact (X7) has significant positive influence on farmer’s attitude while the rest two annual income (X4) and mass media contact (X8) have significant negative influence. To reach an optimum model of prediction, these six significant variables were included in the stepwise multiple regression analysis (Table 9).

Results from stepwise multiple regression analysis (Table 9) shows that farmer’s individual extension contact had the highest contribution (45.7 percent) in predicting their attitude towards government extension services. On the other hand, training experience had the second highest contribution (20.5 percent) in prediction. Educational qualification, farm size, annual income, and mass extension contact had 6.5 percent, 2.7 percent, 4.4 percent, and 1.2 percent contribution, respectively.

Table 8: Contributing variables to explain farmer’s attitude towards government extension services (n =125).

|

Variables entered |

Unstandardised coefficient (B) |

Standardised coefficient (β) |

t value |

Collinearity statistics |

|

|

Tolerance |

VIF |

||||

|

Constant |

32.848 |

12.532 |

|||

|

Education qualification (X1) |

0.597 |

0.213 |

4.813*** |

0.804 |

1.243 |

|

Farm size (X2) |

5.690 |

0.313 |

5.645*** |

0.512 |

1.953 |

|

Training experience (X3) |

2.170 |

0.446 |

10.600*** |

0.890 |

1.123 |

|

Annual income (X4) |

-4.776E-5 |

-0.262 |

-5.385*** |

0.669 |

1.494 |

|

Organisational participation (X5) |

0.225 |

0.044 |

0.977 |

0.785 |

1.274 |

|

Agricultural knowledge (X6) |

0.054 |

0.085 |

1.843 |

0.742 |

1.348 |

|

Individual extension contact (X7) |

1.118 |

0.290 |

4.980*** |

0.464 |

2.155 |

|

Mass extension contact (X8) |

-1.032 |

-0.160 |

-3.274* |

0.658 |

1.519 |

R2 = 0.817; Adjusted R2 = 0.804; F= 67.67***, * = significant at 5% level of significance; *** = Significant at 0.1% level of significance.

Table 9: Overview of the stepwise multiple regression analysis illustrating the variables contributing to the dependent variable (n =125).

|

Model |

Variable entered |

B |

β |

R2 Change |

t value |

F statistics |

|

Constant +X7 |

Individual extension contact |

1.199 |

0.311 |

0.457 |

5.385*** |

103.511 *** |

|

Constant+ X7+X3 |

Training experience |

2.167 |

0.446 |

0.205 |

10.586*** |

119.604 *** |

|

Constant+X7+X3+X1 |

Education qualification |

0.589 |

0.211 |

0.065 |

4.707*** |

107.312 *** |

|

Constant+X7+X3+ X1+X2 |

Farm size |

6.027 |

0.332 |

0.027 |

6.146*** |

92.049*** |

|

Constant+X7+X3+X1+X2 + X4 |

Annual income |

-4.617E-5 |

-0.253 |

0.044 |

-5.215*** |

94.010*** |

|

Constant+X7+X3+X1+X2 +X4 + X8 |

Mass extension contact |

-0.813 |

-0.126 |

0.012 |

-2.711** |

83.745*** |

** = Significant at 1% level of significance; *** = Significant at 0.1% level of significance.

Discussion

Farmer’s overall attitude towards government extension services

As previously observed in the findings, the attitude of farmers towards government extension services were notably unfavourable. This could be attributed to a variety of factors. Often, these services offered by the government face challenges in effectively communicating and addressing the diverse and dynamic needs of farmers. Bureaucratic hurdles, insufficient resources, and a lack of timely and relevant information contribute to a perceived disconnect between farmers and these government initiatives (Waheduzzaman et al., 2018). Additionally, farmers might have felt that these services are not adequately tailored to local conditions, leading to scepticism about their practical utility. This, coupled with a historical pattern of unmet expectations, might have resulted in a general distrust and unfavourable attitude among the IFMC farmers towards government extension services.

On the other hand, the IFMC farmers were mostly in agreement with the statement that government extension services, although crucial, are incapable of providing all sorts of comprehensive resolutions for farmers. Perhaps this is due to the diverse and intricate character of agriculture. The considerable diversity among farms in terms of scale, agricultural produce, and geographical circumstances poses a formidable obstacle for a centralised service to adequately cater to each unique requirement of farmers (Goodwin and Gouldthorpe, 2013). Furthermore, farmers are compelled to swiftly adjust to rapidly evolving technological advancements and climate conditions, potentially impeding the ability of government services to keep up (Collier and Dercon, 2014). In addition, extension services are additionally hindered from delivering comprehensive solutions by resource constraints, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and obsolete procedures (Cook et al., 2021).

Furthermore, farmers with limited financial means and resources may encounter obstacles when attempting to utilise services provided by the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE) (Jayne et al., 2010). They may find the expenses related to participation in various programmes, such as lodging and transportation, to be unaffordable. The capacity of these farmers to obtain essential agricultural knowledge and skills offered by DAE programmes may be impeded by this discriminatory characteristic.

However, the IFMC farmers were in agreement that one of the most efficient and grassroot level officers of DAE, i.e., the Sub Assistant Agriculture Officers (SAAOs) usually plays a crucial role in delivering reliable and practical extension services aimed at solving farmer’s problems. By means of their empirical approach, these officers impart significant knowledge, pragmatic resolutions, and pertinent counsel that directly confront the obstacles encountered by farmers (Ahsan et al., 2022). In doing so, they enhance the efficacy and dependability of the extension services they provide.

Factors affecting farmer’s attitude towards government extension services

It was found that farmer’s individual contact with different extension media and sources was the most significant factor in tailoring their attitude towards government extension services. On the other hand, mass extension contact was the least contributing factor, and it had a negative influence in predicting farmer’s attitude. The significant contribution of farmer’s individual extension contact (with UAOs, AEOs, SAAOs, NGO workers, input dealers) rather than mass extension contact to predicting their attitude underscores the importance of personalised interactions. When farmers have direct and individualised contact with extension services, it enhances the relevance and effectiveness of the information provided (Aker, 2011). This one-on-one engagement likely fosters a sense of trust and better addresses the specific needs and concerns of farmers, contributing to a more positive overall attitude.

However, the IFMC farmer’s contact with different extension sources were found very low to medium in extent in the study area. This low to medium contact of farmers can be attributed to limited access and awareness. Farmers may have faced challenges such as a lack of infrastructure, poor connectivity, and limited exposure to technology, hindering their engagement (Maina and Maina, 2012). Additionally, inadequate promotion and outreach efforts by extension services may contribute to the lower-than-desired levels of interaction with these informational channels.

On the other hand, farmer’s training and educational qualifications can positively influence their attitude towards government extension services by giving them useful knowledge and skills to enhance their agricultural practices (Mwamakimbula, 2014). Farmers feel more empowered, trusting, and confident in the extension services when they believe the training is pertinent, approachable, and meets their needs well. This leads to a more positive attitude in general. Having a favourable level of education among farmers could advance and improve attitudes towards certain aspects (Narmada and Jahromi, 2019). However, farmer’s education and training level were not up to the mark in the study area, which calls for due attention.

Farmer’s farm size and annual income were found to be important factors associated with their attitude, which is consistent with the findings of Goswami (2016) that also found an association of size of water body and annual income in developing the attitude of the respondents. Farmers having larger farms might have a more positive attitude towards government extension services because it offers advantages that make the adoption of cutting-edge technologies easier. Farmers with large farms typically possess greater resources, which allows them to attend training programmes, better utilise extension services, and put advised strategies into practice (Antwi-Agyei and Stringer, 2021). All these actions help farmers develop a positive perception of government support. On the other hand, farmers with lower incomes might have a positive attitude towards government services. This could be because extension services have been developed to help low-income farmers overcome obstacles by providing them with financial support and useful ideas to improve their financial circumstances (Muyanga and Jayne, 2006).

Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, the findings of the study revealed that most of the IFMC farmer’s attitude towards government extension services was moderately to highly unfavourable. Even though there were positive attitude towards the dependency on Sub-Assistant Agriculture Officer’s (SAAO’s) services, there were severe dissatisfaction regarding the consistency and comprehensiveness of other government extension services. In addition to these findings, factors like farmer’s individual extension contact and training experience played the most significant part in explaining their attitude while educational qualification, farm size, annual income, and mass extension contact played little but significant contribution. It is needless to say that farmer’s attitudes towards government extension services are crucial for their active participation and engagement, leading to better adoption of recommended agricultural practices and technologies. A proactive approach involving improved communication, tailored solutions, and increased transparency is needed to turn farmer’s unfavourable attitudes towards extension services. Implementing feedback mechanisms, addressing specific needs, and showcasing successful case studies can rebuild trust and demonstrate the value of extension services. A collaborative approach involving private sector initiatives, research institutions, and local communities is essential to supplement government efforts and offer a more adaptable support system for farmers. Targeted awareness campaigns, leveraging digital platforms and mobile technologies, and regular training sessions, workshops, and field demonstrations can enhance farmer’s contact with individual level extension sources. Implementing targeted and practical workshops, seminars, and demonstration programs can enhance farmer’s training and education levels. Promoting access to modern educational resources, such as online courses, agricultural extension materials, and mentorship programs, can contribute to continuous learning and skill development among farmers. Implementing targeted programs that alleviate financial burdens, such as subsidised inputs or access to credit, can demonstrate the government’s commitment to supporting low-income farmers and foster a more positive attitude towards extension services.

Acknowledgements

The funding for this study is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Bangladesh.

Novelty Statement

This piece of research tried to determine the attitude level of the farmers towards government extension services through the development of a robust, equal appearing interval scale. The scale was developed by confirming both validity and reliability, and then the final scale was measured through the Likert scale of attitude measurement. However, in addition to this methodological innovation, the determination of factors influencing the attitude of the farmers was also robust using the stepwise regression method.

Author’s Contribution

As principal author, MFH formulated the fundamental concept of the study and finalised the final draft of the manuscript. NK assembled the necessary research instruments and gathered field data. SS conducted the data analysis and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. MRS conducted a literature review and drafted the preliminary version of the manuscript, while AS completed the final draft and served as the corresponding author. The final manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all of the authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest; however, sadly, during the preparation of the manuscript, author Nazmunnahar Kolpona had passed away.

References

AGEP (Agricultural growth and employment programme). 2013. Programme document. Available at: https://bangladesh.um.dk/en/-/media/country-sites/bangladesh-en/danida/ agric ultural20growth20and20employment20programme2020 13-2018.ashx.

Agholor, I.A., N. Monde., A. Obi. and O.A. Sunday. 2013. Quality of extension services: A case study of farmers in Amathole. J. Agric. Sci., 5(2): 204-212. https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v5n2p204

Ahsan, M.B., G. Leifeng., F.M.S. Azam., B. Xu, S.J. Rayhan., A. Kaium. and W. Wensheng. 2022. Barriers, challenges, and requirements for ICT usage among sub-assistant agricultural officers in Bangladesh: Toward sustainability in agriculture. Sustainability. 15(1): 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010782

Aker, J. C. 2011. Dial “A” for agriculture: a review of information and communication technologies for agricultural extension in developing countries. J. Agric. Econ., 42(6): 631-647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00545.x

Antwi-Agyei, P. and L.C. Stringer. 2021. Improving the effectiveness of agricultural extension services in supporting farmers to adapt to climate change: Insights from northeastern Ghana. Clim. Risk Manag., 32: 100304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100304

Arifullah, M., A. Zahan., M.M. Rana. and M. Adil. 2014. Attitude of the rural elite farmers towards extension activities performed by personnel of department of agricultural extension. Agric., 12(1): 96-102. https://doi.org/10.3329/agric.v12i1.19586

Baiyegunhi, L.J.S., Z.P. Majokweni. and S.R.D. Ferrer. 2019. Impact of outsourced agricultural extension program on smallholder farmer’s net farm income in Msinga, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Technol. Soc., 57: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.11.003

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS). 2022. Preliminary report on population and housing census. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Dhaka. Statistics and Informatics Division, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Available at: https://bbs.gov.bd/site/page/47856ad0-7e1c-4aab-bd78-892733bc06eb/Population-and-Housing-Census.

Bangladesh Economic Review. 2023. Chapter 7: Agriculture. Finance Division, Ministry of Finance, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Available at: https://mof.portal.gov.bd/site/page/28ba57f5-59ff-4426-970a-bf014242179e/Bangladesh-Economic-Review-2023.

Banglapedia. (n.d.). Phulbari Upazila (Dinajpur District). Available at https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Phulbari_Upazila_(Dinajpur_District). Last accessed 10.01.2024

Biswas, B., B. Mallick., A. Roy. and Z. Sultana. 2021. Impact of agriculture extension services on technical efficiency of rural paddy farmers in southwest Bang. Environ. Chall., 5: 100261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100261

Bloom, B.S. 1956. Taxonomy of education objective: The classification of education goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: Longmans.

Chowdhury, A.H., H. Odame. and C. Leeuwis. 2014. Transforming the roles of a public extension agency to strengthen innovation: Lessons from the national agricultural extension project in Bang. J. Agric. Educ. Ext., 20(1): 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2013.803990

Cochran, W.G. 1977. Sampling techniques (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. Inc.

Collier, P. and S. Dercon. 2014. African agriculture in 50 years: smallholders in a rapidly changing world? World dev. 63:92-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.001

Cook, B.R., P. Satizábal. and J. Curnow. 2021. Humanising agricultural extension: A review. World Dev. 140: 105337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105337

Das, S., M.E. Haque., M. Rokonuzzaman., S. Saha. and S.R. Saha. 2021. Attitude of haor farmers towards extension services. Ann. Bang. Agric., 25(2): 61-75. https://doi.org/10.3329/aba.v25i2.62413

Edwards, A.L. 1957. Techniques of attitude scale construction. New York: Appleton Century Crafts, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1037/14423-000

Edwards, A. L. 1969. Techniques of attitude scale construction. Bombay: Vakils, Feffer and Simons Private Ltd.

George, D. and P. Mallery. 2003. SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 Update (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goodwin, J.N. and J.L. Gouldthorpe. 2013. Small farmers, big challenges: A needs assessment of Florida small-scale farmer’s production challenges and training needs. JRSS. 28(1): 3.

Goswami, B. 2016. Factors affecting attitude of fish farmers towards scientific fish culture in West Bengal. Ind. Res. J. Ext. Edu. 12(1): 44-50.

Hasan, M.F., M.F. Hossain, M.S. Rahman and S. Sarmin. 2019. Factors contributing to farmers attitude towards practicing aquaculture in Dinajpur district of Bangladesh. Bang. J. Ext. Educ., 31(1 and 2): 77-85.

Hasan, M.F., M.R.K. Rain., M.A.S. Mondol. and S. Sarmin. 2020. Farmer’s attitude towards farm mechanisation. Bang. J. Ext. Educ., 32(2): 41-52.

Hossain, Q.A. 2017. Effectiveness of farmer-to-farmer training in dissemination of farm information. PhD thesis, Sher-e-Bangla Agricultural University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Jayne, T.S., D. Mather. and E. Mghenyi. 2010. Principal challenges confronting smallholder agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev., 38(10): 1384-1398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.002

Kabir, M.H. and M.S. Islam. 2023. Effectiveness of public and private extension services in building capacity of the farmers: A case of Bangladesh. Sarhad J. Agric., 39(1): 101-110. https://doi.org/10.17582/journal.sja/2023/39.1.101.110

Kaur, J., P.S. Shehrawat, and Q.J.A. Peer. 2014. Attitude of farmers towards privatisation of agricultural extension services. Agric. Sci. Dig., 34(2): 81-86. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-0547.2014.00020.2

Likert, R. 1932. A technique for the measurement of attitude. Arch. psychol., 140.

Maina, W.N. and F.M.P. Maina. 2012. Youth engagement in agriculture in Kenya: Challenges and prospects. Update. 2.

Masanja, I., G.L. Shausi. and V.J. Kalungwizi. 2023. Attitude of farmers and factor associated with farmers attitude towards agricultural extension services provided by private organisations in Kibondo district, Kigoma region, Tanzania. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Soc., 41(10): 556-566. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajaees/2023/v41i102200

Moyo, R., and A. Salawu. 2018. A survey of communication effectiveness by agricultural extension in the Gweru district of Zimbabwe. J. Rural Stud., 60: 32-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.03.002

Muyanga, M., and T.S. Jayne. 2006. Agricultural extension in Kenya: Practice and policy lessons (No. 680-2016-46750).

Mwamakimbula, A.M. 2014. Assessment of the factors impacting agricultural extension training programs in Tanzania: a descriptive study. PhD thesis, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa, United States.

Narmada, R., and A.B. Jahromi. 2019. Factors affecting attitude of Iranian pistachio farmers toward privatising extension activities: case of Kerman province. Iran Agric. Res. 38(2): 17-24.

Nordic Consulting Group (NCG). n.d. Evaluation of agricultural growth and employment programme (AGEP) in Bangladesh. Available at: https://ncg.dk/our-work/19-news/522-evaluation-of-agricultural-growth-and-employment-programme-agep-in-bangladesh.html

Onyemekihia, F., R.C. Onyemekonwu. and F.A. Ehiwario. 2021. Farmers attitude towards commercialised extension system in Delta State, Nigeria. ADAN J. Agric., 2(1): 33-43. https://doi.org/10.36108/adanja/1202.20.0140

Pandey, M., D. Solanki. and S. Pandey. 2020. Attitude of farmers towards the agricultural extension system of the State Department of Agriculture. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci., 9(4):352-358. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2020.904.041

Pawlak, K. and M. Kołodziejczak. 2020. The role of agriculture in ensuring food security in developing countries: Considerations in the context of the problem of sustainable food production. Sustain. 12(13): 5488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135488

Rebecca, A.A. 2012. Attitude of women farmers towards agricultural extension services in Ifelodun local government area, Osun State. Am. J. Soc. Manag. Sci., 3(3): 99-105. https://doi.org/10.5251/ajsms.2012.3.3.99.105

Robi, D. T., A. Bogale, S. Temteme, M. Aleme and B. Urge. 2023. Evaluation of livestock farmer’s knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the use of veterinary vaccines in Southwest Ethiopia. Vet. Med. Sci., 9(6): 2871-2884. https://doi.org/10.1002/vms3.1290

Sebeho, M.A. 2016. Perceptions and attitude of farmers and extensionists towards extension service delivery in the Free State Province, South Africa. PhD thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Takahashi, K., R. Muraoka. and K. Otsuka. 2020. Technology adoption, impact, and extension in developing countrie’s agriculture: A review of the recent literature. J. Agric. Econ., 51(1): 31-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12539

Thurstone, L.L. and E. J. Chave. 1929. The measurement of attitudes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Uddin, E., Q. Gao. and M.M.U. Rashid. 2016. Crop farmer’s willingness to pay for agricultural extension services in Bangladesh: cases of selected villages in two important agro-ecological zones. J. Agric. Educ., 22(1): 43-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1389224X.2014.971826

Waheduzzaman, W., B.V. Gramberg. and J. Ferrer. 2018. Bureaucratic readiness in managing local level participatory governance: A developing country context. Aust. J. Public Adm., 77(2): 309-330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12256

To share on other social networks, click on any share button. What are these?