Female Preferences for Call Properties of Giant Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa)

Female Preferences for Call Properties of Giant Spiny Frog (Quasipaa spinosa)

Yanyan Yu1,2,3, Yizhong Hu1, Qipeng Zhang1, Rongquan Zheng1,4,*, Bing Shen1, Shenshen Kong1 and Ke Li1

Linear relationship between pulse rate and dominant frequency for Q. spinosa.

Linear relationship between pulse rate and fundamental frequency for Q. spinosa.

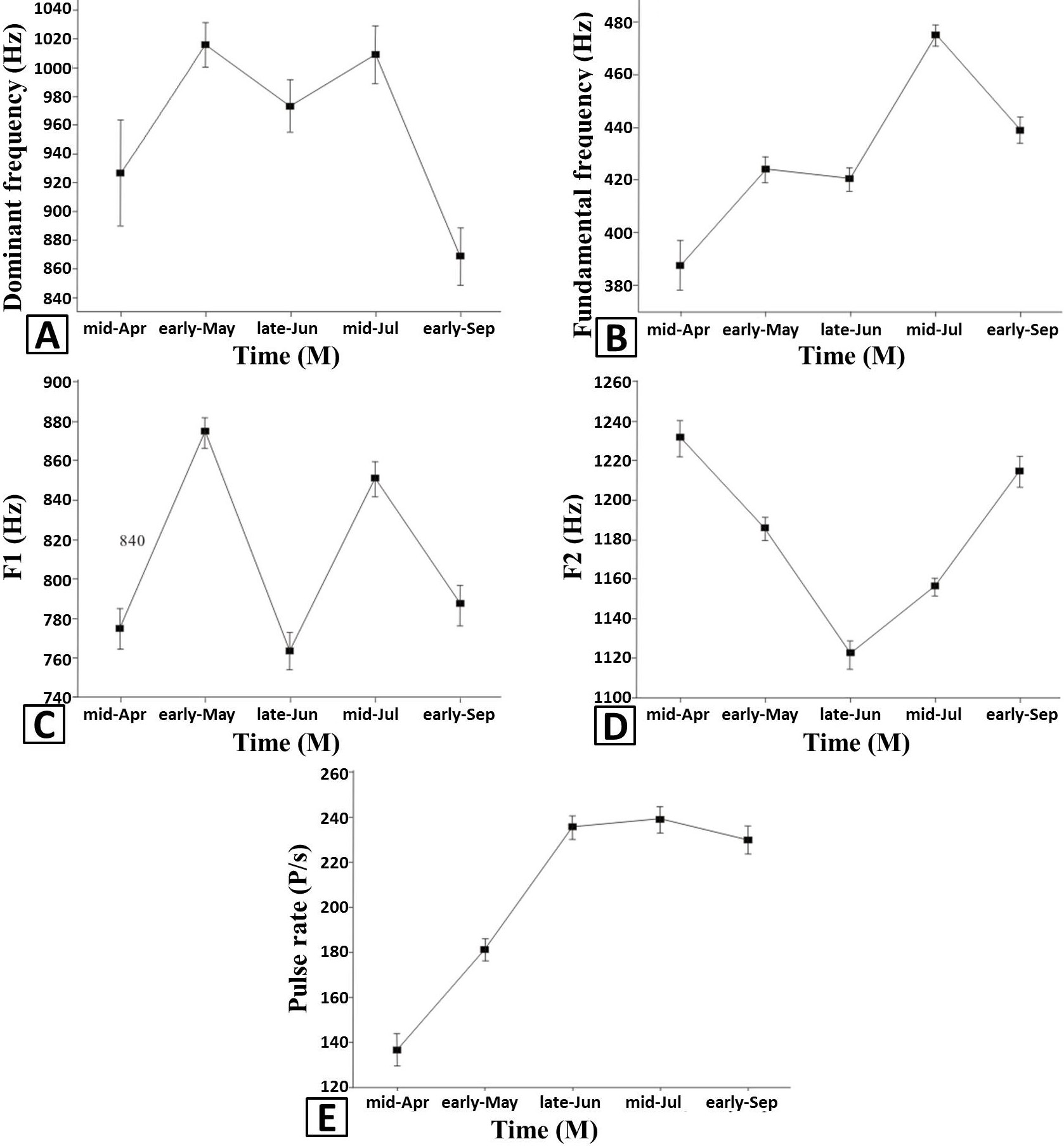

Different variation tendencies in dominant frequency (A), fundamental frequency (B), the first formant (F1, C), the second formant (F2, D), and pulse rate (E) across five breeding periods (mid-April, early May, late June, mid-July, and early September). Each point represents the mean (±SE) acoustic signals of 40 males.

Phonotactic scores of females to call models varying in call duration (A). Scores were calculated by dividing each control trial by the mean control trial of that female. Each point represents the mean (±SE) of 10 females. The number of notes used in the control trials was 4. Graphs illustrating the phonotactic scores of females to call models varying in call rate (B). Each point represents the mean (±SE) of 10 females. The call rate used in the control trials was 15n/min.